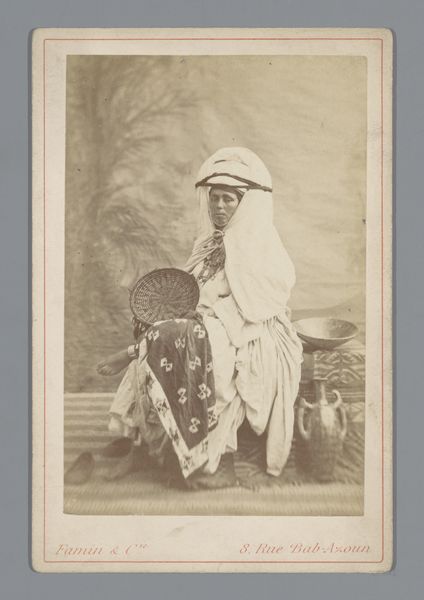

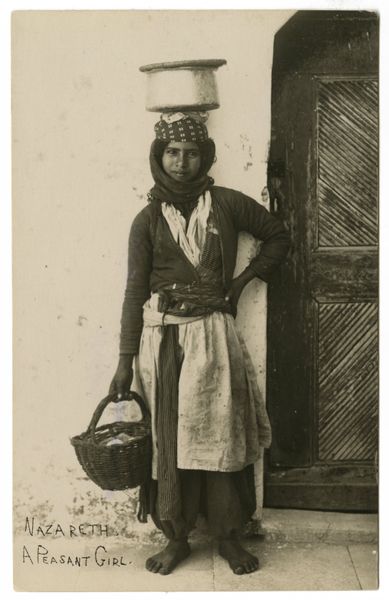

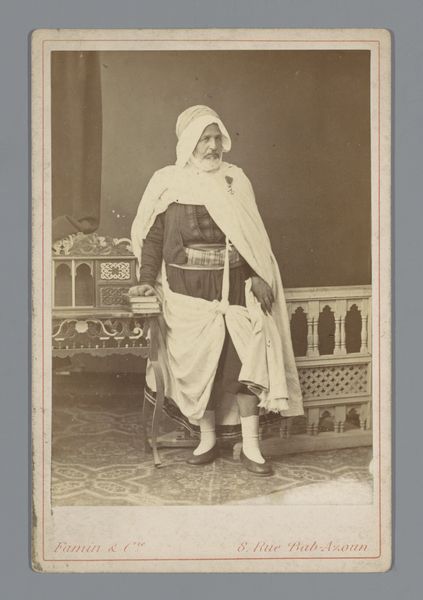

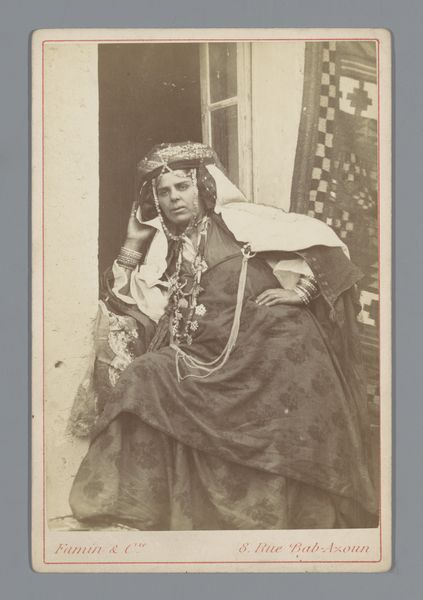

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

landscape

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

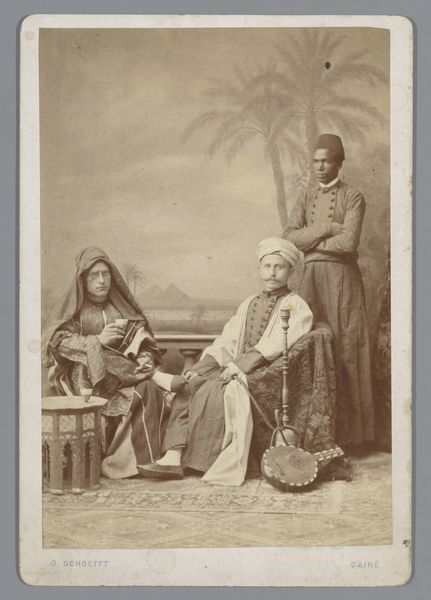

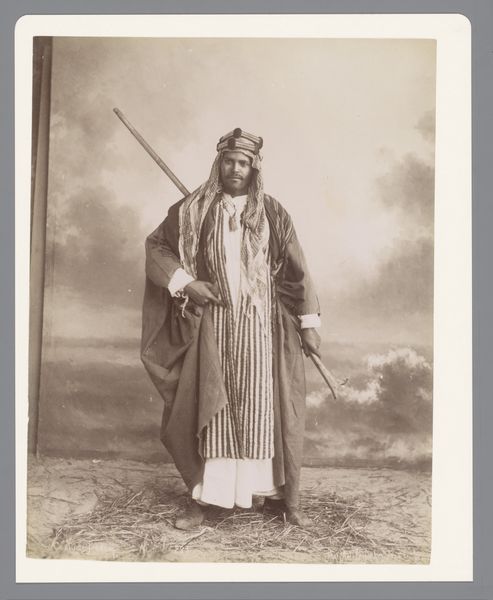

orientalism

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 281 mm, width 210 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

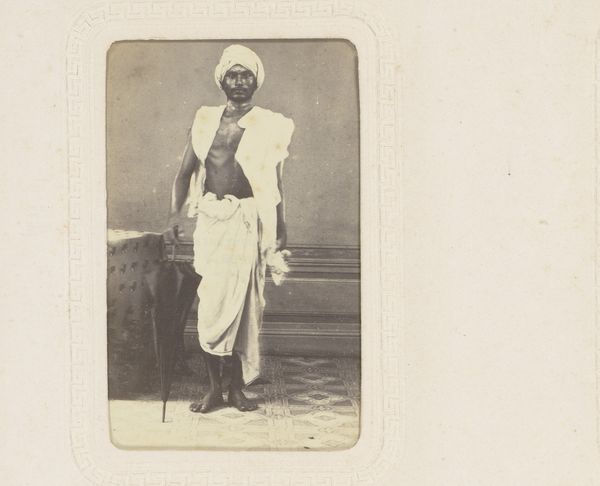

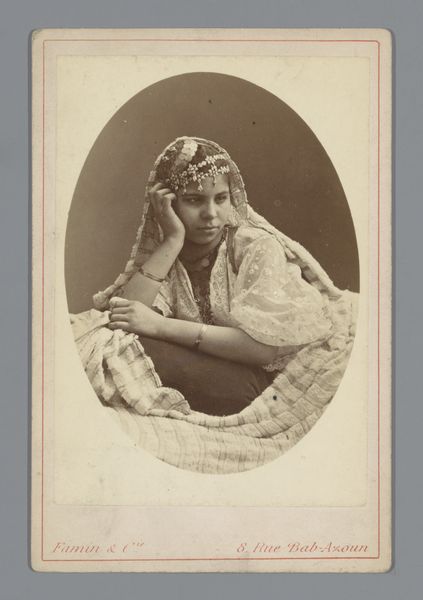

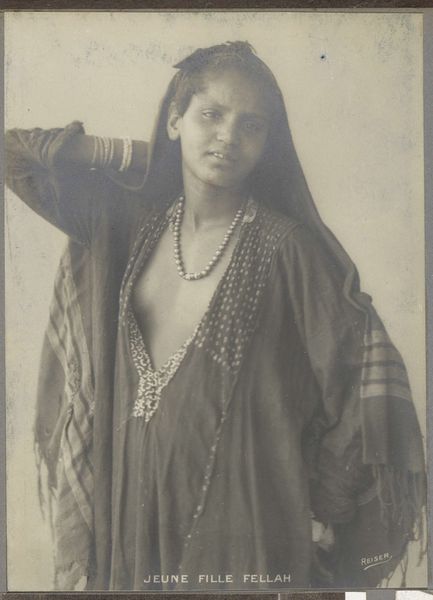

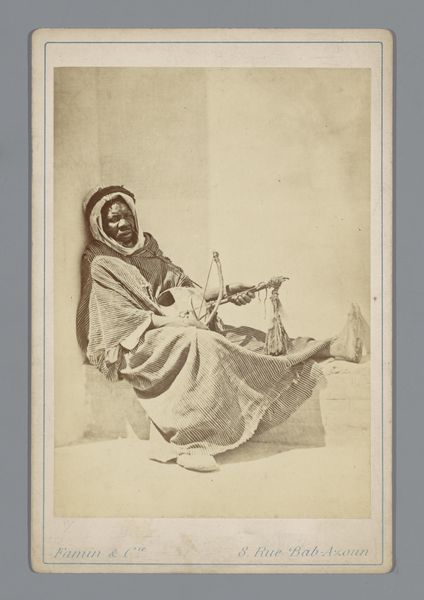

Curator: Here we have a rather compelling albumen print titled “Portret van een Arabische jongen met ezel, Egypte,” dating from between 1890 and 1900, credited to C. & G. Zangaki. Editor: There’s an undeniable air of stillness about this image. The tones are muted, almost sepia, which enhances that quietness, that sense of being transported back in time. Curator: The Zangaki brothers, of Greek and Egyptian heritage, were quite active in the late 19th century, producing a large body of photographic work catering to the burgeoning tourist trade in Egypt. What we see here is very much a product of its time, fitting neatly within the orientalist aesthetic. The materiality itself, this albumen process, involves coating paper with egg whites, making it highly sensitive to light. It really speaks to the labor-intensive process behind even seemingly simple portraiture back then. Editor: It absolutely carries those historical implications. The soft focus on the young man and the donkey softens their perceived social standing, placing them almost like props within a constructed landscape intended for Western consumption. Do we know about the subject himself? Was he a worker or just posed for the picture? Curator: Sadly, no, his identity is lost to time. But this image invites us to consider the dynamic between photographer, subject, and audience. The materials used would have been sourced from colonial trade routes and processes, reminding us of the social structures in which photography existed. This isn't merely a depiction of Egypt; it is a document molded by Western perceptions of that time. The fact it has found its way into the Rijksmuseum raises the question, isn't it? About representation, who has a voice and who is framed within it? Editor: Absolutely. Its display implicates our present gaze as much as their past vision. A picture presented, reworked and reviewed. What was exotic becomes archived. I now consider the institutional implications more pointedly: the way the colonial gaze of the late 19th century translates into our museums today. Curator: Precisely. Considering this photo involves thinking about image circulation and its endurance. A lens of labor and materiality enriches our understanding. Editor: A poignant piece to contemplate and re-evaluate. Curator: Indeed. Food for thought, as we say!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.