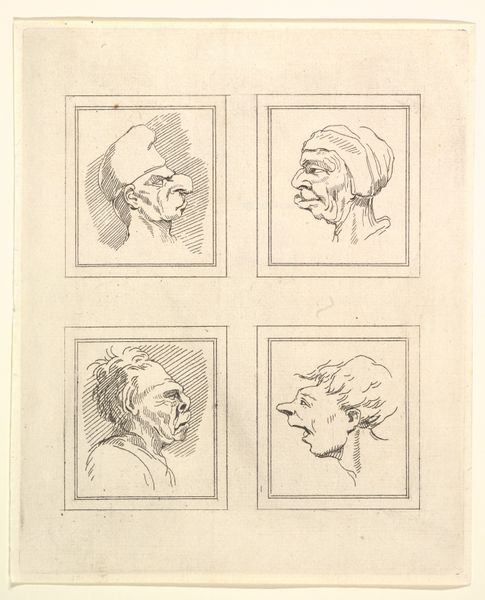

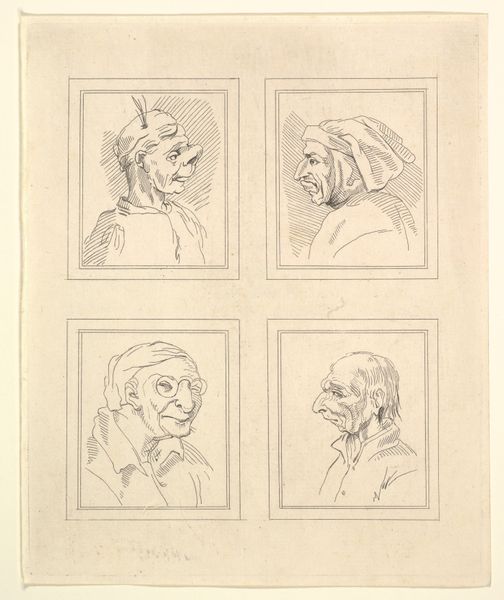

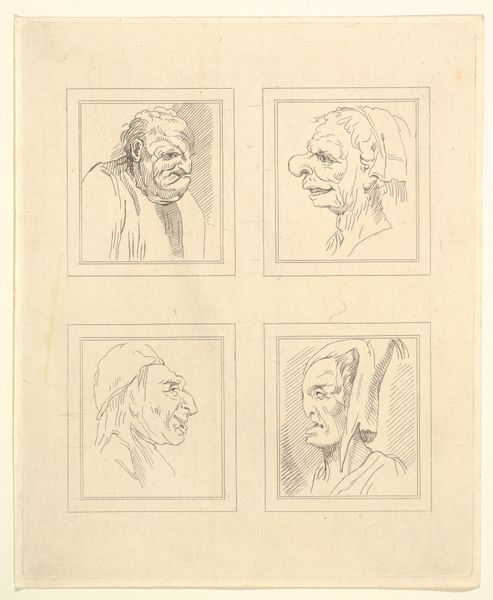

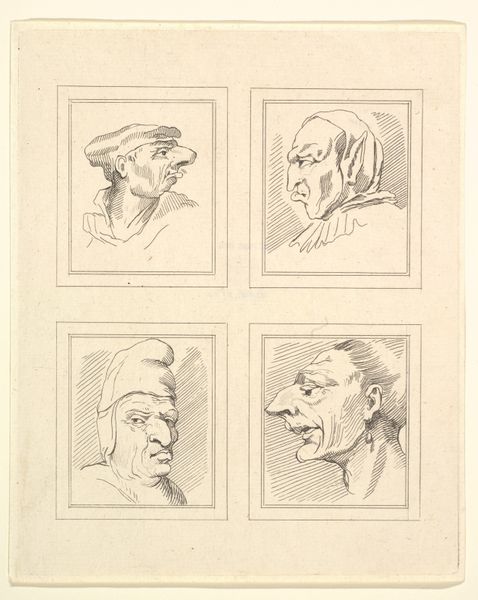

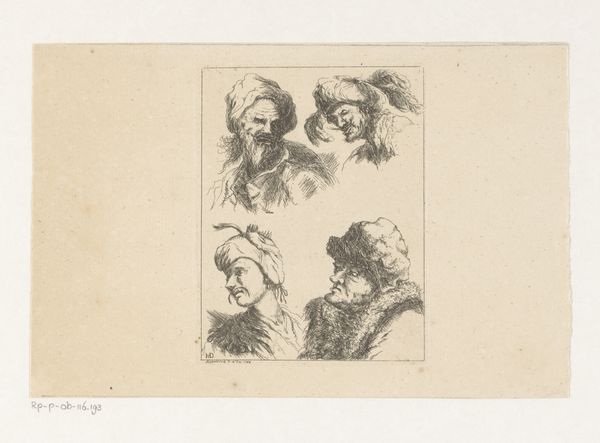

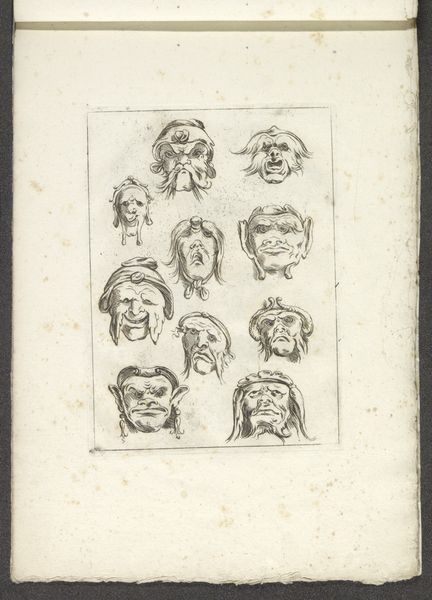

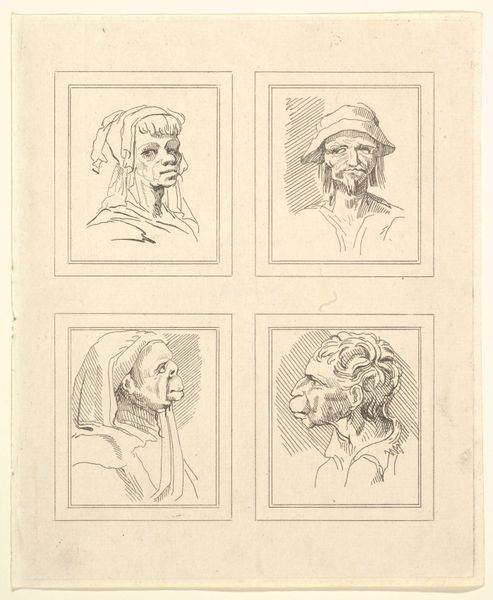

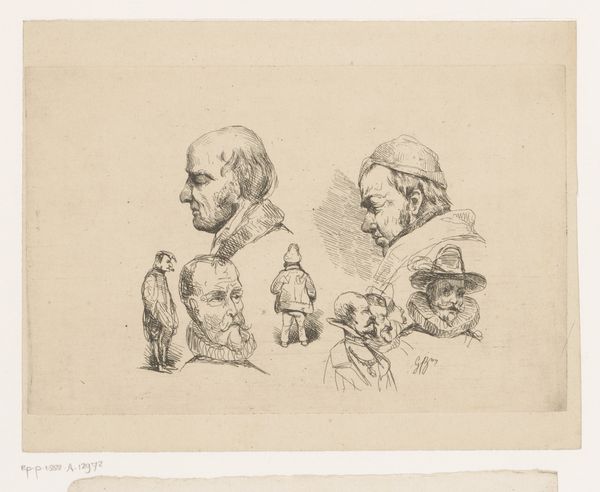

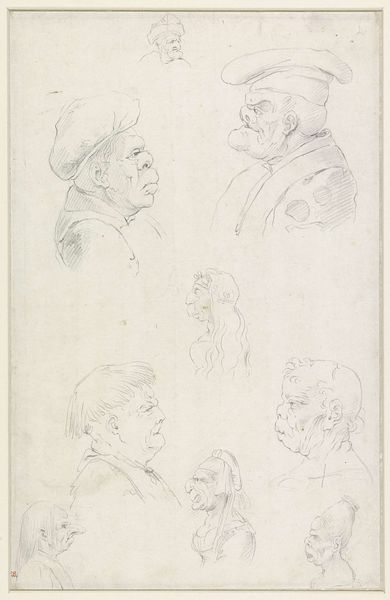

Four Heads (from Characaturas by Leonardo da Vinci, from Drawings by Wincelslaus Hollar, out of the Portland Museum) 1786

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

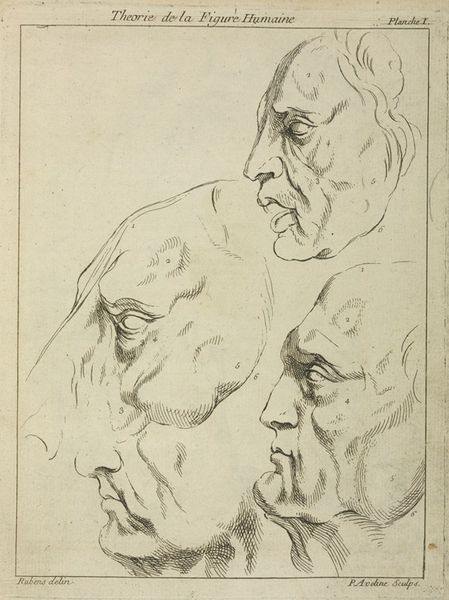

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

caricature

#

engraving

Dimensions: Plate: 7 11/16 x 6 5/16 in. (19.5 x 16 cm) Sheet: 7 7/8 x 6 9/16 in. (20 x 16.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Standing before us is "Four Heads (from Characaturas by Leonardo da Vinci, from Drawings by Wincelslaus Hollar, out of the Portland Museum)," an engraving by Wenceslaus Hollar dating back to 1786. Editor: My initial impression is one of discomfort and fascination. There's a starkness to these grotesque features that is somehow both repulsive and incredibly engaging. Curator: Hollar's work exists as an appropriation of da Vinci’s caricature studies. Let’s consider how artists adopt and reimagine existing works across different socio-historical contexts. The social satire and power dynamics implicit within each head reflect the norms and hierarchies prevalent during both artists’ eras. How does this lens invite us to engage with representation in contemporary society? Editor: Right. The labor that went into this piece as an engraving needs recognition. I see lines etched so precisely to give form to each caricature, likely using a burin. Engraving wasn't cheap or easy. Consider, too, who the intended audience might have been – presumably, wealthy consumers. Did it serve a political purpose through accessibility, or merely fuel bourgeois sensibilities by mocking particular physiognomies? Curator: That question of labor and intended audience speaks volumes about its historical placement, I think. Who is allowed to be "caricatured," and who is doing the caricaturing? This resonates through time, bringing forward the original power relationships to ask: who does representation serve, and at what cost? This directly speaks to social commentary on privilege and exclusion. Editor: So, if these faces originally belonged to studies by da Vinci, how much are they simply mimicking, versus serving a representational, localized reality here through the engraver's skill and agency in choosing certain subjects, or emphasizing certain details? Curator: Absolutely, because, from the vantage of today, these images call attention to how easily visual representations, filtered through different contexts, are utilized to classify and stereotype. So let’s not stop short, instead we should critique the system where those stereotypes came to form. It helps deconstruct what the image presents in its simple forms. Editor: Looking closely at the textures and shading rendered via precise engraving lines also really grounds the idea that these aren't just images; they're labor materialized, commenting on its specific social context. Curator: It prompts us to reflect on whose perspectives get amplified. Whose are silenced through such displays, whether originally or by its continuation throughout history? It compels critical self-reflection for anyone encountering the artwork and invites necessary dialogue on these issues within present times. Editor: So, as a method for challenging these images, recognizing and celebrating both craft and its social underpinnings is essential, helping provide tangible insights into labor practices as resistance. Curator: By contextualizing "Four Heads," we not only acknowledge its complex layers but simultaneously interrogate art history’s role in shaping identity, power and how we move beyond passive consumption of it into active understanding and advocacy.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.