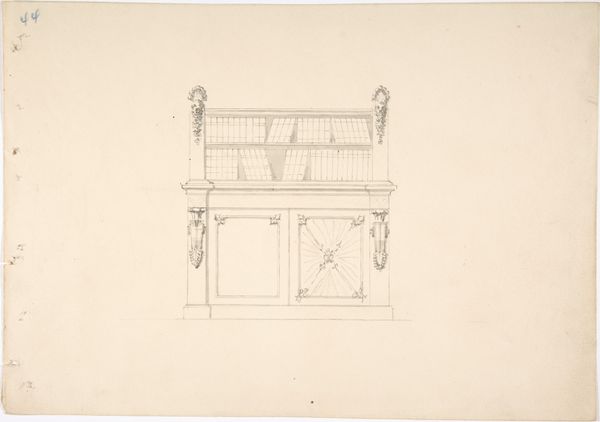

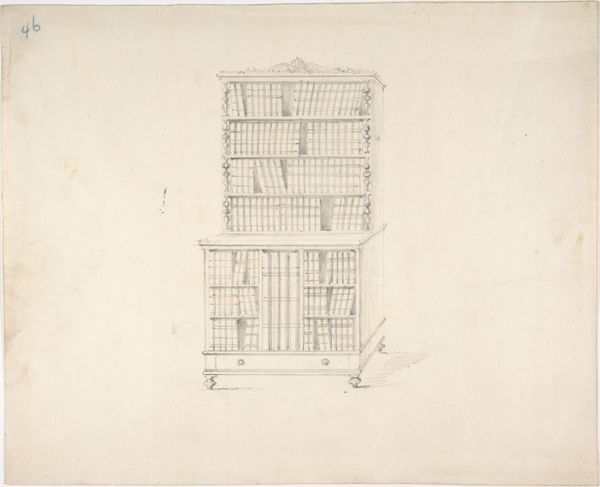

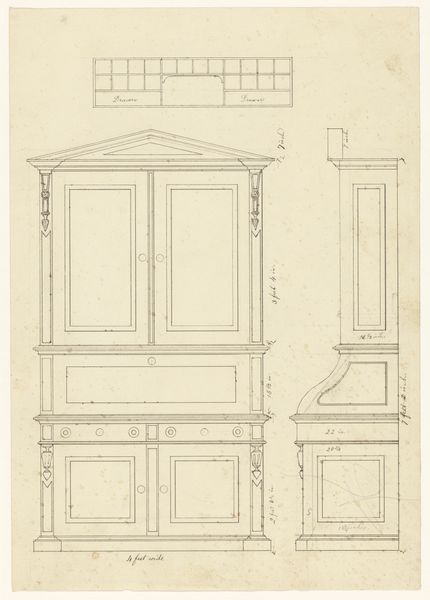

Design for a Large Bookcabinet, with a Door at Left and a Chair at Right 1800 - 1850

drawing, print, pencil

drawing

neoclacissism

book

geometric

pencil

line

Dimensions: sheet: 10 13/16 x 14 15/16 in. (27.5 x 38 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Looking at this pencil drawing, created sometime between 1800 and 1850, one gets a profound sense of order, wouldn't you agree? Editor: I do, although it’s a very still kind of order, like a stage set waiting for the players. A quiet anticipation almost. The precise lines hint at both knowledge and confinement. Curator: Indeed. This is a design sketch titled "Design for a Large Bookcabinet, with a Door at Left and a Chair at Right," and currently residing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The artist is, unfortunately, anonymous. Editor: I find it interesting how this cabinet, in its presumed grandeur, hints at access to knowledge. But simultaneously, this visual access feels ironically unattainable behind closed doors, as it were. This suggests knowledge might be hoarded. And the artist's anonymity amplifies this lack of access—it poses a crucial question, who holds the right to knowledge? Curator: I think it also speaks volumes, quite literally, about the period itself. We see Neoclassicism evident in the symmetry and the detailed ornamentation of the cabinet and the chair. It is a very controlled and refined aesthetic, after all. I almost feel like it would be oppressive. Editor: Oppressive, but also carefully constructed to promote ideals of reason and order! The meticulous lines could signify a need for categorization in an era marked by Enlightenment thought and also emerging colonialism. Curator: You’re right, there's definitely a statement about control and intellectual domination subtly woven into this composition. It gives one food for thought, that’s certain. It does also make me think of a dollhouse, everything rendered as pristine miniatures. What narrative potential lies within that cabinet if we could shrink ourselves down and peek at each title, each page. Editor: A space where personal reflection meets the structured expectations of a specific time and place. It speaks of what’s emphasized, celebrated, and therefore, preserved—while also quietly highlighting who is excluded. Curator: Yes, it reveals its beauty layer by layer. A dialogue with history, wouldn't you say? Editor: Precisely. The act of observing history can itself be a form of transformation, and I suppose that transformation must start with that first critical gaze.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.