#

pencil drawn

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

pencil work

Dimensions: height 127 mm, width 81 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

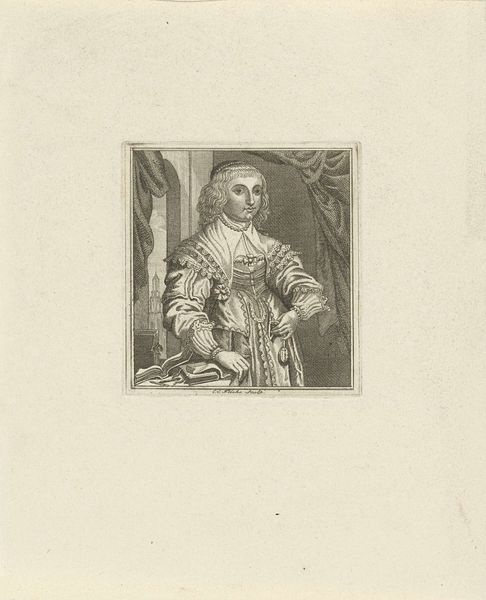

Curator: The work before us is a print identified as a portrait of John Stuart, dating between 1729 and 1802 and attributed to Franz Nikolaus Rolffsen. Editor: There's something rather stiff and formal about it, isn't there? The figure looks confined, almost as though imprisoned by his ornate garments and the architectural setting behind him. Curator: Portraits like this one functioned as symbols of power and status. The depiction of John Stuart draped in ermine and lace conveys a clear message about his position within the British aristocracy. This imagery was circulated through prints, reinforcing social hierarchies. Editor: Precisely, it's about visual coding! The ermine immediately signifies nobility and justice, while the specific type of lace often pointed to membership within a particular order or rank. It’s like a uniform that speaks volumes about identity and affiliation. He's even wearing a prominent belt with what seems to be a ceremonial buckle; symbols of both earthly power and some larger ideology. Curator: Indeed. What's also interesting here is that Rolffsen, though of German origin, seems to have catered to British tastes for formal portraiture, which at the time played an important role in defining the self-image of the nation’s ruling class. Disseminating images like this solidified John Stuart as part of a visual lineage of powerful individuals. Editor: The column backdrop is so interesting; it serves not merely as setting but rather as a grounding element for his entire image of status and respectability. And you know what I see when I study it a little closer, even though the technique is mostly linear... a vulnerability. Perhaps a quiet admittance of what burdens come along with wearing such heavy garments of responsibility. Curator: Perhaps we're also reading into the pose itself; it certainly lacks dynamism. Consider, however, the context: printmaking allowed for widespread reproduction. Prints became key in distributing political ideologies and reaffirming a sense of cultural identity, as portraits like these filtered into public and private collections, shaping historical memory. Editor: Looking closely, I am fascinated by how it conveys its message: not just about individual fame, but, more fascinatingly, as it reflects what we project onto such symbols and individuals. Curator: So, we witness here more than the likeness of John Stuart. Editor: Exactly.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.