drawing, painting, print, watercolor, pencil, engraving

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

painting

# print

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

pencil

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

watercolor

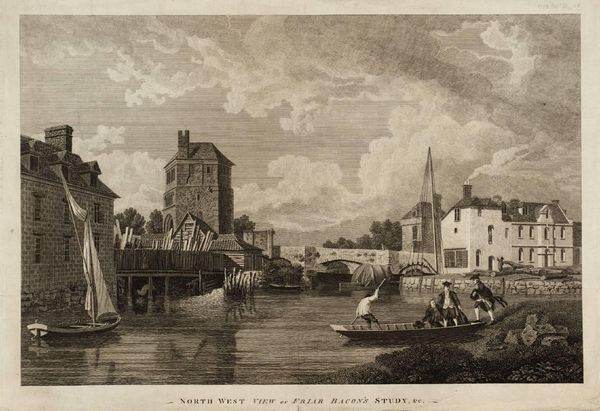

Dimensions: height 298 mm, width 439 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Gezicht op Paramaribo" by Johan Antonie Kaldenbach, dating roughly between 1770 and 1818. It's a watercolor and pencil drawing. I'm struck by the contrast between the seemingly calm, picturesque scene and what I imagine colonial life was actually like. How do you interpret this work? Curator: Exactly. What appears serene is underpinned by complex power dynamics. This cityscape offers a glimpse into Dutch colonial ambitions in Suriname. Note the composition: a clear separation between the manicured European structures and the natural landscape. What does that separation signify to you? Editor: I guess it highlights the attempt to impose European order onto a different world. Almost as if trying to recreate a sense of "home." Curator: Precisely. But consider the labor that enabled this "home." Where are the enslaved people whose forced labor funded and built Paramaribo? Their absence is a glaring, yet common, visual strategy in colonial art. How does that absence speak volumes to the narratives these images perpetuate? Editor: So, this seemingly innocent landscape is actively obscuring the brutal reality of colonialism. It’s presenting an incomplete, biased picture. Curator: Indeed. This artwork acts as a potent reminder that historical images aren't neutral; they are constructed narratives serving specific ideological purposes. By questioning what's *not* shown, we reveal the historical context and, perhaps, begin to decolonize our own gaze. What new perspectives have emerged for you after this conversation? Editor: I realize now that analyzing the power structures embedded within seemingly tranquil art pieces can reveal crucial aspects of colonial history. Thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.