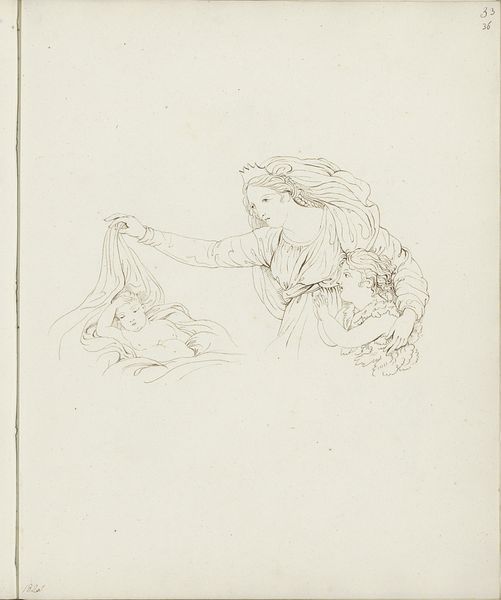

drawing, print, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

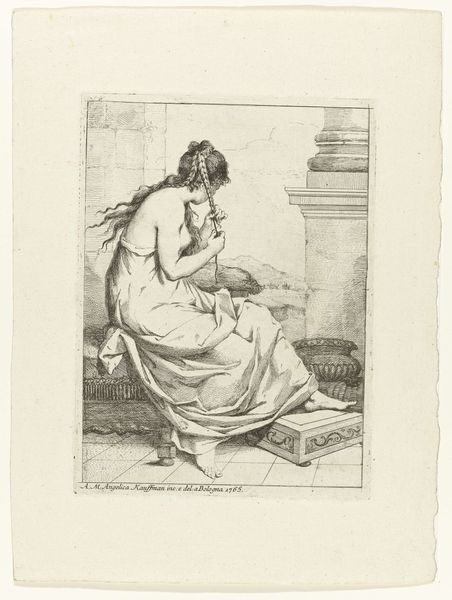

# print

#

figuration

#

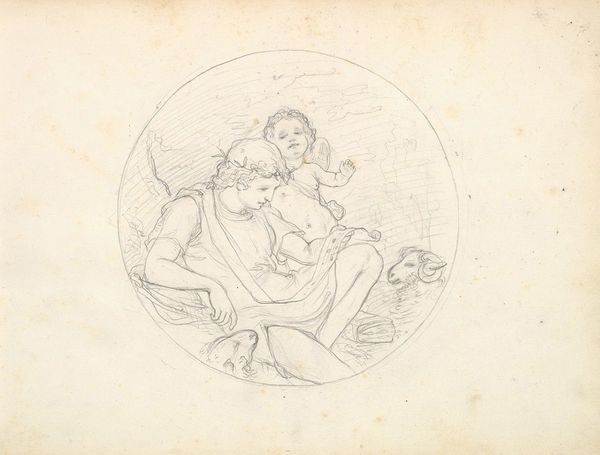

pencil

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 316 mm, width 450 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: So, here we have "Aglaé en Bonifatius van Tarsus," created between 1843 and 1905 by Gustave Joseph Biot. It’s currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. A print on paper, executed in pencil, and it shows a distinct historical narrative. What are your immediate thoughts? Editor: Well, it certainly strikes a melancholic tone, doesn't it? There’s a palpable sense of longing or weariness conveyed in the figures’ posture and facial expressions, but I’m really interested in the way that this scene in rendered as print using pencil - quite intricate in some passages, like the patterned fabric. How does Biot’s choice of medium affect its social impact? Curator: It’s a fascinating point. Prints, even detailed pencil prints such as this one, had wider circulation capabilities than a painting of a similar scale and detail might, offering opportunities for consumption outside elite circles. Biot's utilization of relatively inexpensive materials democratizes the imagery of martyrdom in a time where this narrative may resonate politically. Editor: I see. The circular framing further accentuates this intimate scene as a portrait. Yet, "history-painting" is amongst the given themes - do you believe that designation overshadows what is communicated about their relationship in the visual language? Curator: Not necessarily, because I see it working in tandem. "Aglaé en Bonifatius van Tarsus" engages with a very particular historical and religious context. This rendering seems quite aligned with the developing romanticization of Christian martyrs and converts that was occurring in art during the nineteenth century, yet this specific rendering forgoes overtly theatrical presentation for quiet emotional affect. The method, too, supports this intention through tonal intimacy. Editor: Absolutely. You see, I keep thinking about how printmaking in this period facilitates art reproduction for middle-class audiences. So what this signifies isn't just about history-painting or fine-art drawing – the intersection of these is equally important because of their availability for home display! Curator: I agree completely. I wonder, also, if there is an argument for Biot responding to a need that had to accommodate that middle class, expanding its visual consumption. It speaks of clever negotiations, perhaps even challenging how devotional imagery functions and who consumes it, right? Editor: Definitely, making the art accessible while upholding traditional themes demonstrates Biot’s commitment to democratization as a public-facing practice during the 19th century. This close look gives much to think about and appreciate from different points. Curator: Yes, looking at Biot’s methods has changed how I interpret it. It speaks to its complexity and layers that resonate still, particularly about democratization of imagery.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.