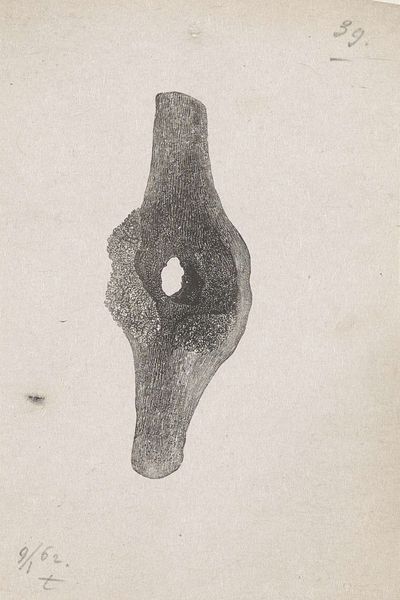

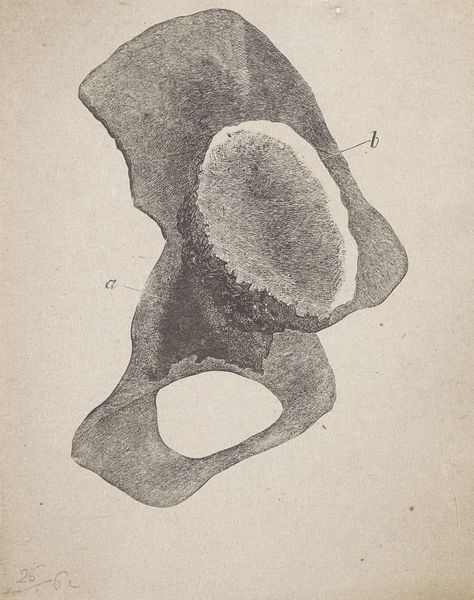

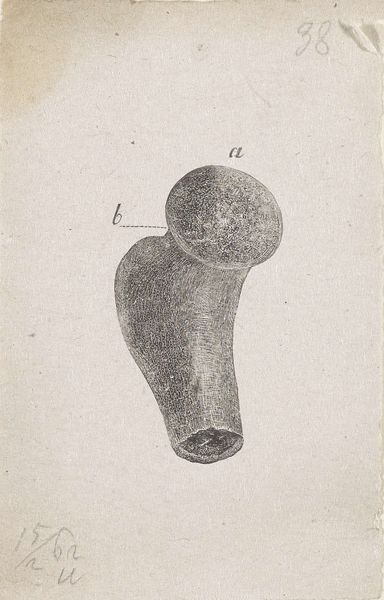

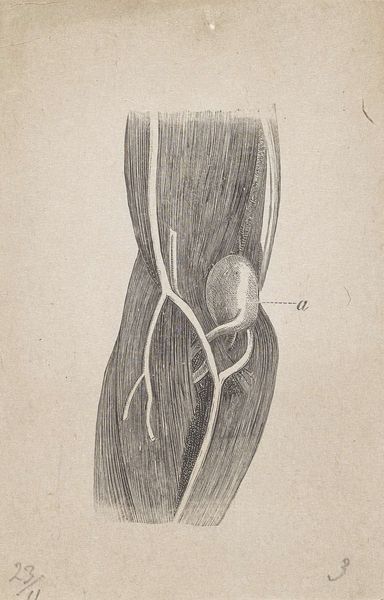

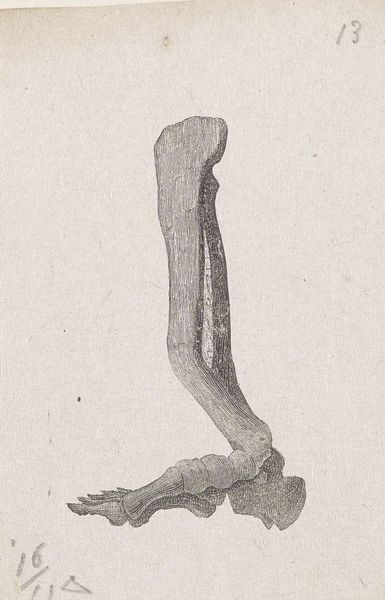

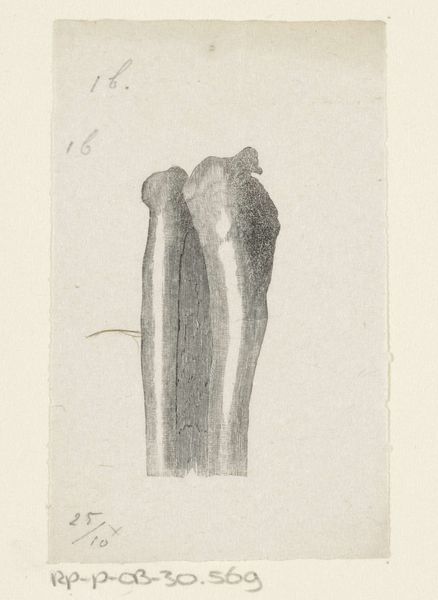

drawing, graphite

#

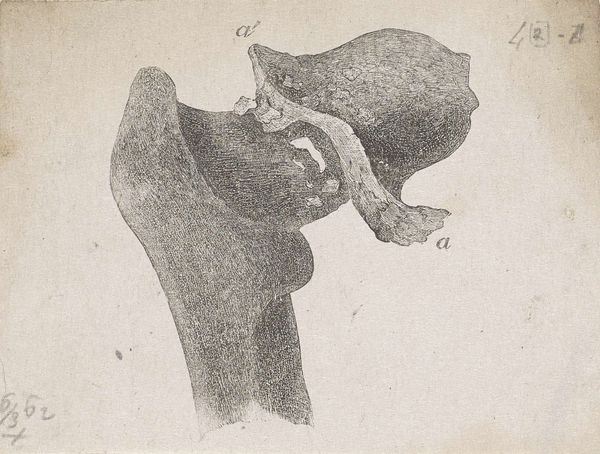

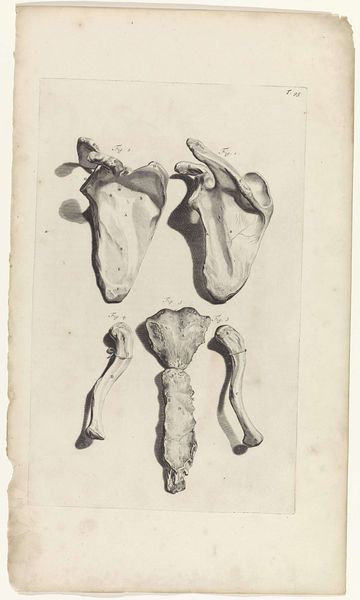

drawing

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

graphite

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 89 mm, width 53 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

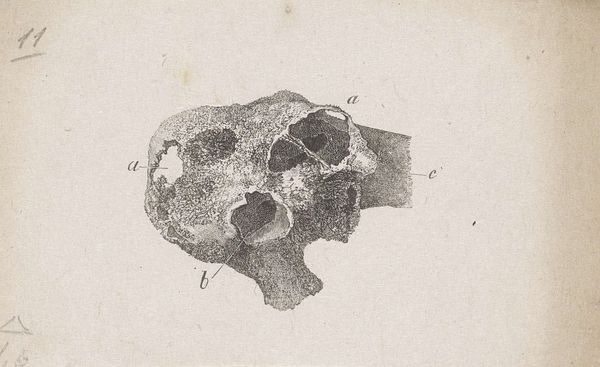

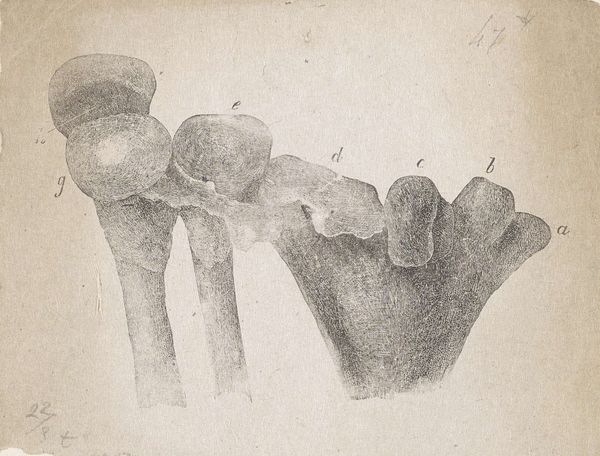

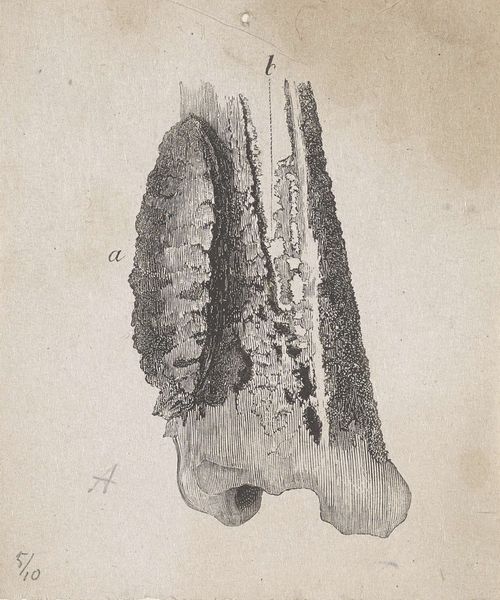

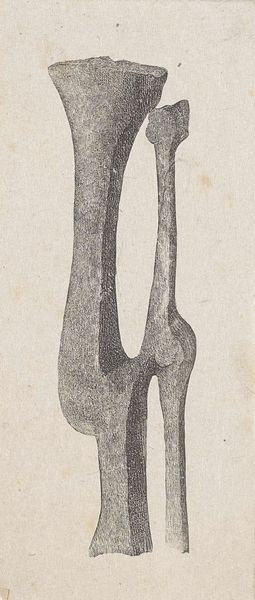

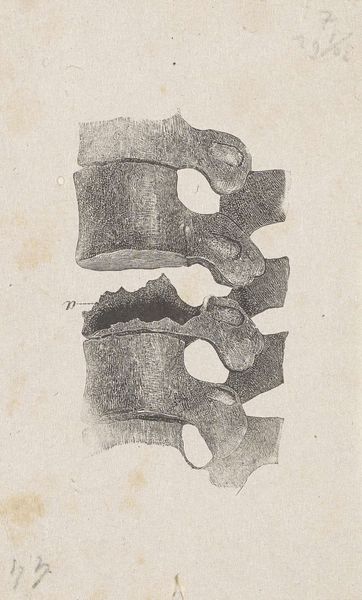

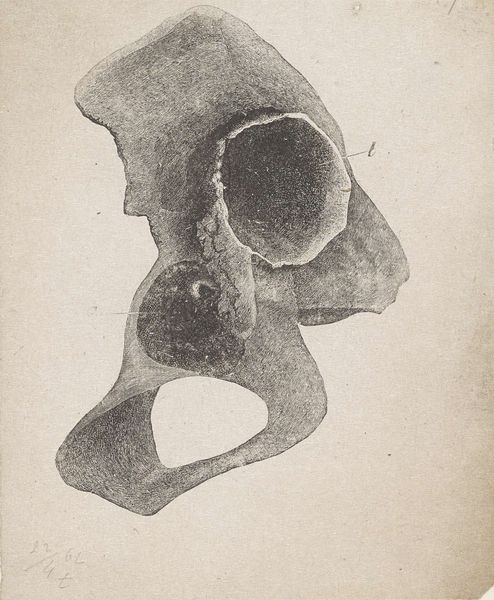

Curator: So here we have 'Menselijk bot met een afwijking'—'Human bone with a deviation'—by Isaac Weissenbruch, dating from 1836 to 1912. It's currently residing here at the Rijksmuseum. Executed with graphite and pencil, it presents... well, what's your initial impression? Editor: A somber still life! But fascinating in its strangeness. There's a stark beauty to its decay or imperfection, however you read it. Like a geological memento mori, maybe. What draws you to it? Curator: For me, it's the artist's meticulous rendering of material degradation using just graphite and pencil. It’s the meeting of science, labor, and the morbid, isn't it? Imagine Weissenbruch painstakingly building up those tiny marks. This detailed work involved a deep study of material reality. Editor: I love that tension—the almost clinical precision used to depict something so intrinsically human, fragile, and imperfect. The texture of the bone... it almost feels papery in places, or like dried clay. It’s the kind of tactile experience that challenges our contemporary separation of science from lived experience. It is quite academic art though, I do find this genre quite distant... Curator: Distant, yes, but not detached. Consider the period it was created in, perhaps in a teaching environment, there's a connection between craft production and this drawing's historical application. It reminds us about historical labour dynamics as we imagine students making such pieces for medical training. Editor: Yes, that practical dimension reframes my perspective. Looking closer, that deviation suggests so much about labor itself - what caused it? What impact might that deviation had on that body's daily life and their ability to be productive and profitable. What story of working life does it tell? Curator: Exactly, that’s the beauty of approaching it from a materialist lens. By delving into material practice and historical contexts, it transcends the clinical to address labour, economic history, and health access across socio economic gradients! What do you think you'll take away from looking so closely? Editor: A reinforced fascination for detail! I love now considering the production methods by which something tangible becomes transformed and interpreted by labour power. This opens up considerations beyond formal artistic achievements alone, into understanding larger economic and socio-cultural arrangements. Curator: Indeed! And it's prompted a new way to see my work—by looking at it more materialistically, rather than trying to interpret its emotional content.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.