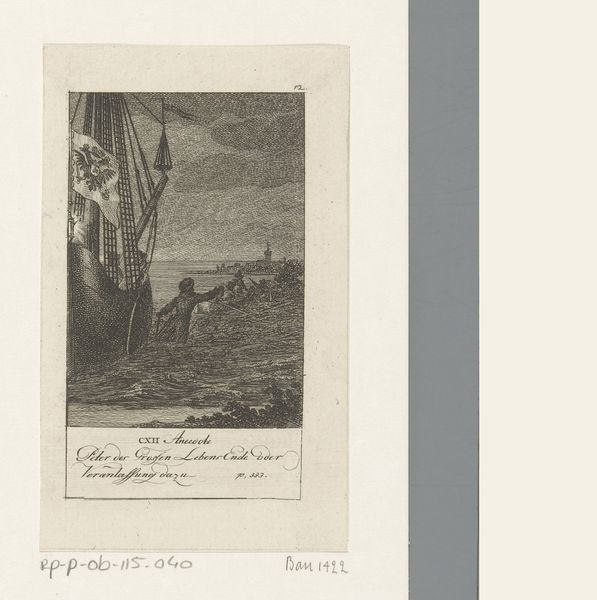

Dimensions: height 111 mm, width 65 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki's "Chronos sluit het jaar af," or "Chronos Concludes the Year," an engraving from 1779. It’s currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It’s strikingly delicate. The muted palette gives it an ethereal, almost dreamlike quality, like looking at a faded memory. Curator: Absolutely. Chodowiecki worked primarily as an printmaker, so the graphic qualities were really important. We see Chronos, Father Time himself, with wings, holding what appears to be a lantern, and a child riding on his shoulders in the clouds. Considering its creation, we should think about the engraving’s status within a culture deeply rooted in Enlightenment ideals and nascent revolutionary thought. How does that affect its reception? Editor: From a material perspective, I’m thinking about the labor involved. Each line is so precise; this isn’t a quick sketch. It involved considerable planning and skill, making this reproduction inherently valuable as an art object and for wider consumption as an easily reproduced symbol. Curator: Precisely. The act of physically etching into the metal plate is one thing, but it gains significance in light of the larger discussions concerning the roles of labor, production, and art-making itself. The symbolism suggests that time both illuminates and carries the next generation, with one year ending and another beginning. How would different demographics interpret the symbolism differently? For instance, someone who belongs to an oppressed population versus an oppressor. Editor: Right, and this engraving was itself made to be consumed, probably reproduced for books, so the labor does intersect with market economics. We also have to account for the rising middle class and their access to cultural symbols. Consider where engravings fell in relation to other more traditionally valorized painting media, which impacts our access points, whether that is philosophical or just for decoration. Curator: Thinking about it that way opens doors for richer interpretations, moving past purely aesthetic judgments toward understanding its wider circulation as a marker of class, labor and meaning. Editor: It really encourages us to engage critically with art history beyond the simple narratives, and more about making, production and use in various contexts.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.