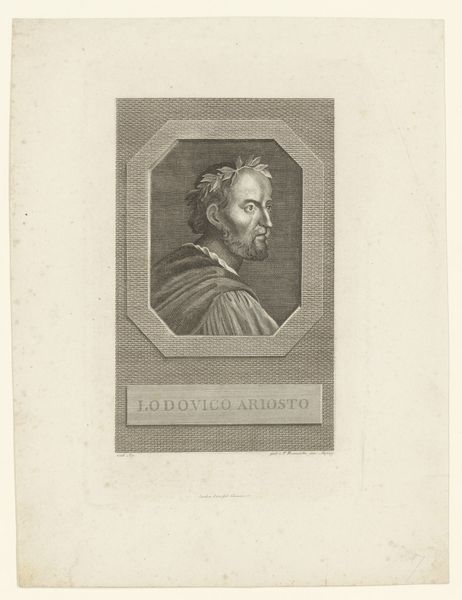

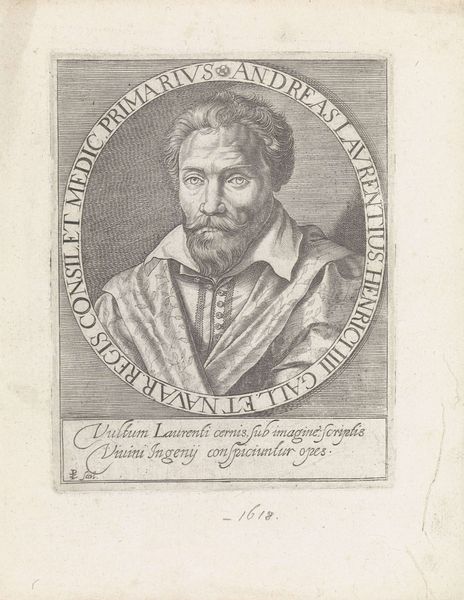

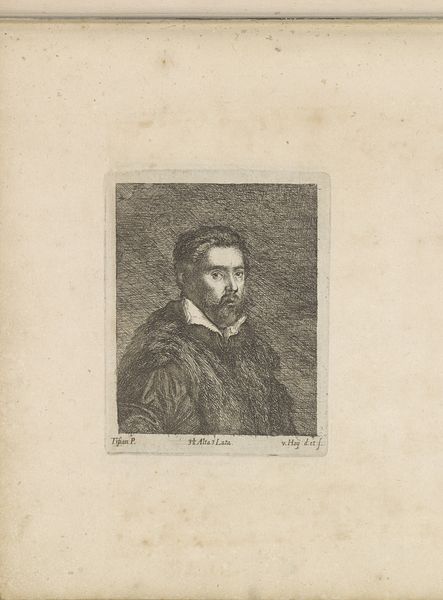

paper, engraving

#

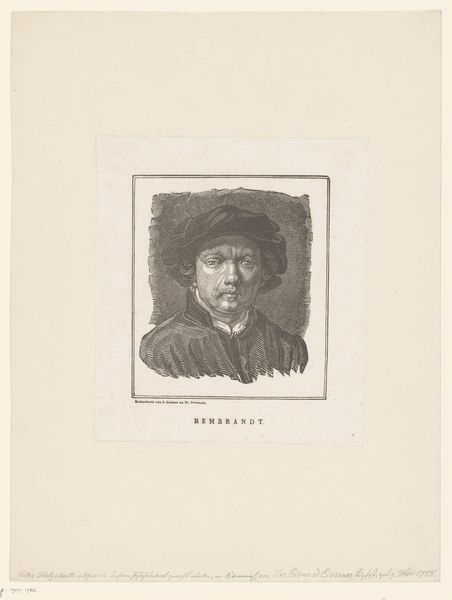

portrait

#

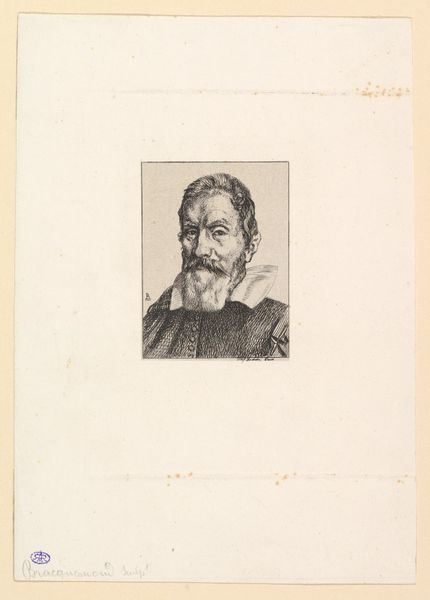

pencil drawn

#

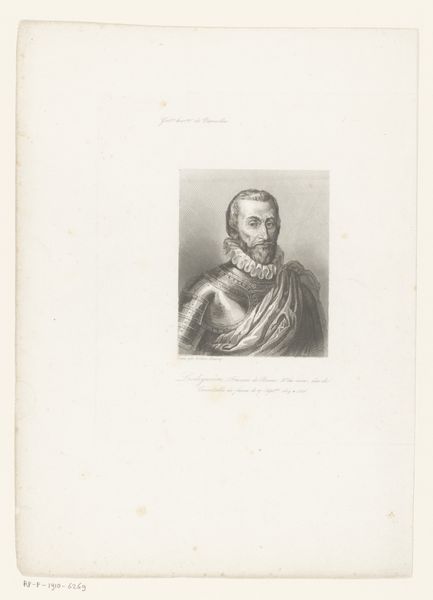

neoclacissism

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

paper

#

pencil drawing

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 351 mm, width 270 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Pietro Ghigi's 1805 engraving, "Portret van dichter Antonio Tebaldeo." It's a portrait, printed on paper. Editor: It feels so...direct, almost confrontational. His eyes bore right through you, even with that laurel wreath perched on his head like he's perpetually ready for a poetry slam. Curator: It’s fascinating to consider the material process of this artwork. An engraving involves meticulously cutting lines into a plate, inking it, and then pressing it onto the paper. This creates a reverse impression, a sort of material echo of the original artistic act. We need to think about what kinds of specialized labor went into making the work—and the market that distributed prints. Editor: I imagine Ghigi, hunched over the plate, translating feeling into that controlled, linear vocabulary of the engraving process. Each line, a little scratch on the surface, slowly revealing the poet’s likeness. You wonder if the controlled medium might reflect something about the poet’s time, perhaps a desire for order and clarity amidst social shifts? Or the pressures on the patron, ordering a reproduction. Curator: Absolutely. And this work, like many engravings, was likely made for wider circulation. That immediately places it within a system of artistic reproduction, dissemination, and consumption. Prints democratize access, but they also transform the artwork into a commodity. Editor: You’re right, but somehow I still see a glimmer of something vulnerable in those eyes, despite the formal pose. Even translated into a mass-producible format, Ghigi manages to suggest Antonio as someone deeply human, contemplating— or maybe even questioning—the very laurels he's wearing. What does artistic celebrity mean when anyone can copy it? Curator: So the labor and materials of production in printmaking invite an analysis of artistic hierarchies—what’s original, what’s a copy, what’s valuable. Editor: All these impressions made on paper invite one last impression from us. It leaves me with the odd feeling of observing someone being observed. Curator: Indeed. I find myself pondering how the industrial context changed the work's purpose.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.