Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

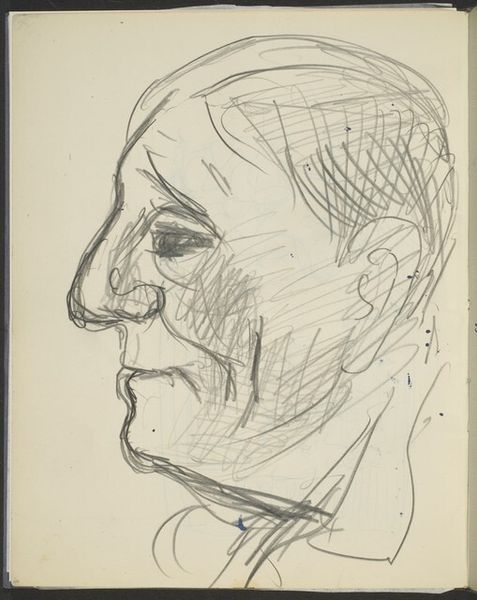

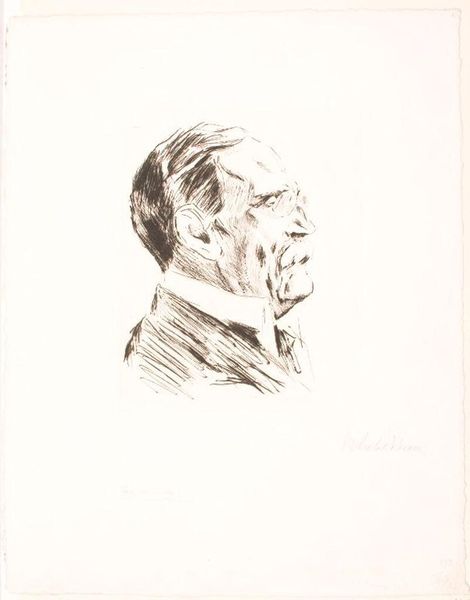

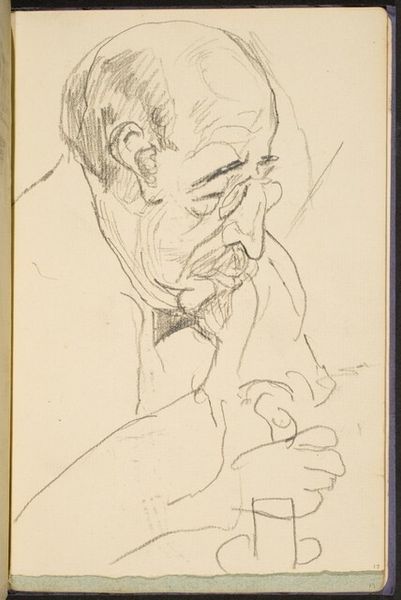

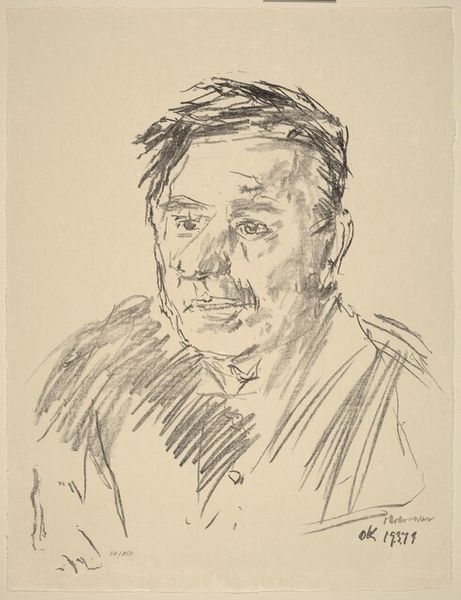

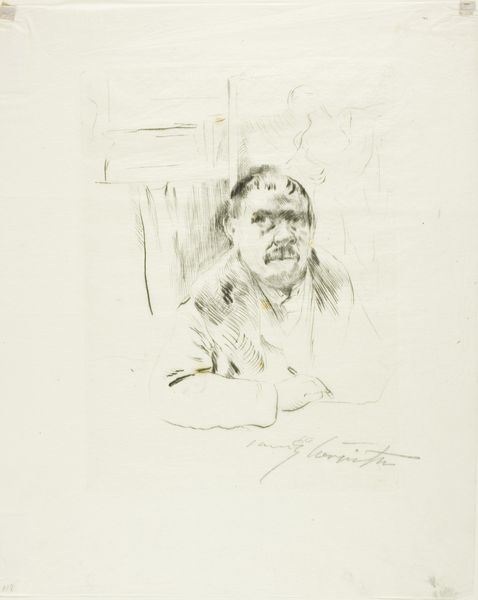

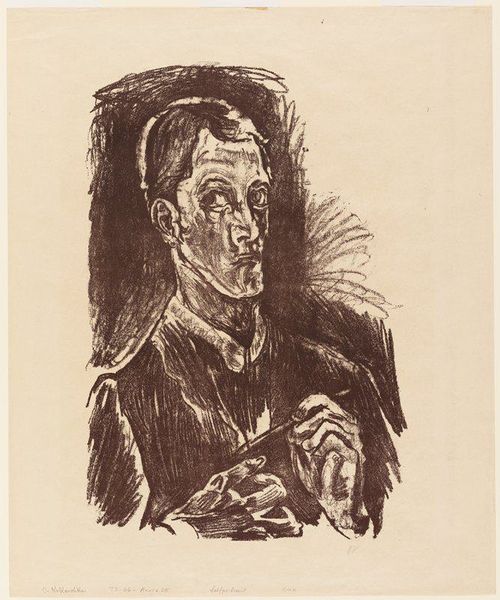

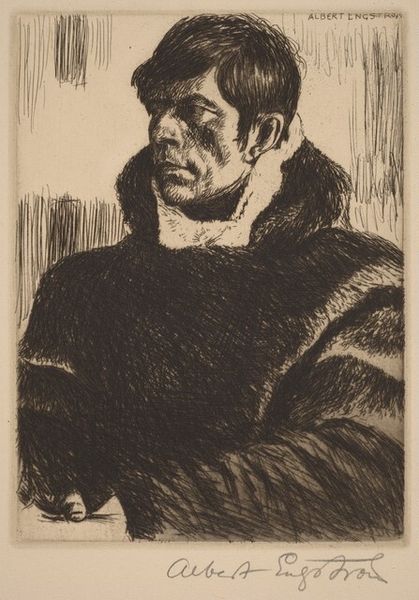

Editor: This is Oskar Kokoschka's "Self-Portrait," created as an etching in 1956. The raw lines and the unconventional color scheme, mostly blues and reds, give it a restless, almost haunted feel. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see a complex layering of anxieties made visible. The etching itself, the deliberate chaos of line, isn’t just a formal choice. Consider the era – post-war. Kokoschka is bearing witness, and burdened by history, by trauma. He is using the language of Expressionism to articulate psychological wounds. Does the fractured line perhaps symbolize a fractured self, pieced back together? Editor: That's interesting. I hadn't thought of it that way. The disjointed lines now feel like more than just an artistic choice, they suggest internal struggle. Curator: Look closely at the gaze. It’s direct, but there’s a weariness there, wouldn’t you agree? A defiance tinged with resignation. The red, green, and blue create shadow that does not mimic reality. Does it distort memory, creating an emotional reality? Editor: It does feel like a gaze from someone who’s seen a lot. I see a visual record of the artist reflecting on their lived experience. It almost makes the self-portrait feel universal, even intimate. Curator: Precisely. And that is the enduring power of symbols. We bring our own cultural memory to it, forming a continuous dialogue between artist, artwork, and audience. What initially appeared like mere line work evolves into a vessel filled with the weight of history, and personal turmoil. Editor: I'll definitely be thinking about Kokoschka’s burden and the weight of history, when I see works like this from now on. Curator: Yes, art has a potent memory all its own. Thank you, that really was a pleasure.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.