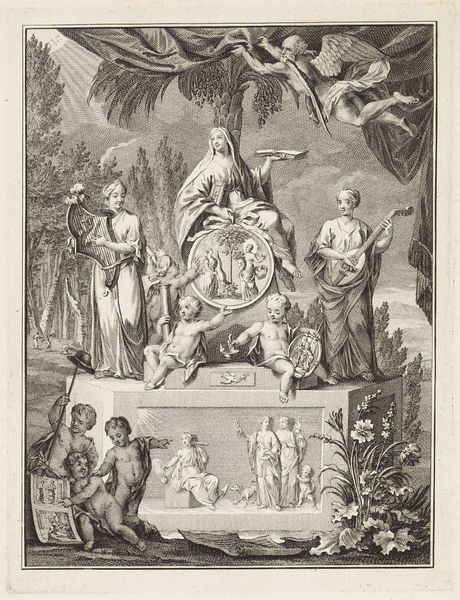

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

#

allegory

# print

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 338 mm, width 394 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: The clean lines of Carlo Lasinio's engraving, titled "Allegorie op Galileo Galilei," created sometime between 1769 and 1838, strikes me as austere. Editor: Yes, there's an almost mechanical quality to it, despite the allegorical subject matter. Look at how the various planes and textures are rendered. What does this say to you about production processes, and the circulation of knowledge in that era? Curator: The very choice of engraving points towards a desire for wider distribution, for disseminating knowledge. What does it tell us about access? Here, Galileo is presented as a figure worthy of such representation; we must situate that within the contexts of scientific discovery versus religious oppression of that time, and recognize that his depiction here serves a certain ideological agenda. Editor: Exactly. The materiality is part of that agenda. It's reproducible, and therefore challenge traditional ideas around high art and originality. We can read that sphere, the set square, and the astronomer's device, within the Neoclassical framework and then connect those depictions to labour, skill, and how such labour was valued. Curator: Furthermore, by placing Galileo among these classically rendered allegorical figures, Lasinio elevates him. He bridges ancient wisdom and enlightenment ideals. There is an overt sense of championing reason, intellect, and scientific inquiry within a time of tremendous sociopolitical change. Consider also the role of angelic figures handing Galileo’s portrait and instruments: how did religious artistic convention work alongside more progressive ideals? Editor: Absolutely, these reproductive techniques democratised images but in very deliberate and stratified ways. What’s striking is the coolness of the print medium and that its effect seems almost didactic when the promise of reproducible work ought to speak to a wider cross section of society. Curator: Agreed, it prompts further exploration regarding power structures intrinsic to the patronage of art and distribution of scientific thought during this period. The figures tell only part of the story. Editor: Exactly, focusing our gaze on its modes of production invites a re-assessment of consumption. Curator: It really shows how the scientific revolution and artistic representation intertwined. Editor: Absolutely, it pushes the viewer to see both the symbolic value and practical reality that constitutes how society creates narratives and reinforces hierarchies of thought and knowledge.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.