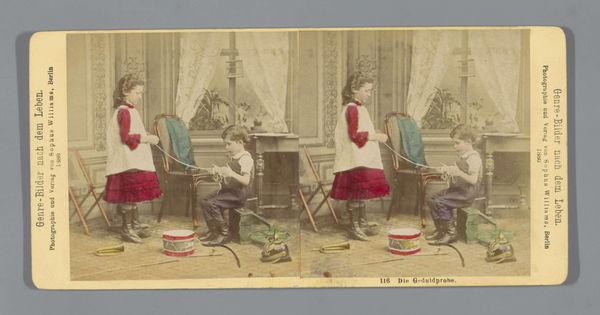

Tafereel met een man achter een bureau en een schoonmakende vrouw 1873 - 1890

0:00

0:00

photography

#

portrait

#

water colours

#

photography

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 88 mm, width 177 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

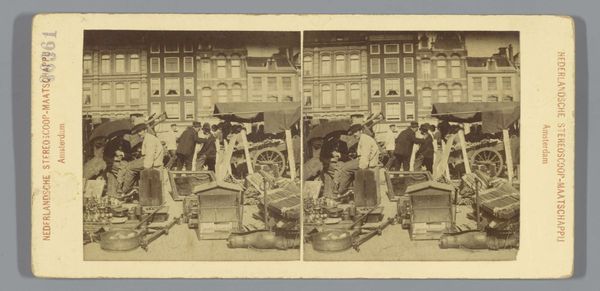

Curator: Here we have a stereoscopic card titled "Tafereel met een man achter een bureau en een schoonmakende vrouw," created by Geschwister Pauly sometime between 1873 and 1890. Editor: Immediately striking is the contrast: a man absorbed in papers while a woman sweeps with obvious displeasure. The domestic tension fairly leaps out, even across the divide of time and medium. Curator: Absolutely. Consider the conditions of production. This isn't merely a staged scene, but a carefully crafted photograph. We see the rise of staged photography attempting to replicate painting, a kind of industrial approach to art making using photography. Editor: I am intrigued by the composition. The figures are rigidly placed; her broom mirroring his posture creates an almost ironic echo. Semiotically, the placement tells its own story: industry against domesticity. It’s visually static but fraught. Curator: Yes, and let's acknowledge the social dynamics on display. The gendered division of labor, made visible and reproducible in a stereoscopic format to reinforce social order, using relatively inexpensive photography accessible to the bourgeoisie. It speaks volumes about class and expectation. This would've been a kind of bourgeois novelty; art for viewing at home, domestic entertainment replicating and reifying these roles. Editor: There's something subtly subversive about capturing such mundane unhappiness. The use of early watercolours over a photograph further softens what otherwise is an unforgiving, albeit staged, look into social disparity. This isn't portraiture, but almost anthropological theatre captured. Curator: Quite, it's genre painting by photographic means. A commentary presented, packaged and consumed in parlors. Even the way we're observing this today, through reproductions, keeps adding to this ongoing narrative of production, labor and inequality. Editor: Indeed. A piece to ponder about visual culture as perpetuation. The composition of light and shadow does, I think, heighten the woman’s weariness versus the man’s focus. A narrative about unequal balance captured neatly. Curator: It encourages us to reflect on the layers of meaning, from the studio production of gender to modern means of distribution to a modern audiences’ engagement in this visual representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.