Copyright: Public domain

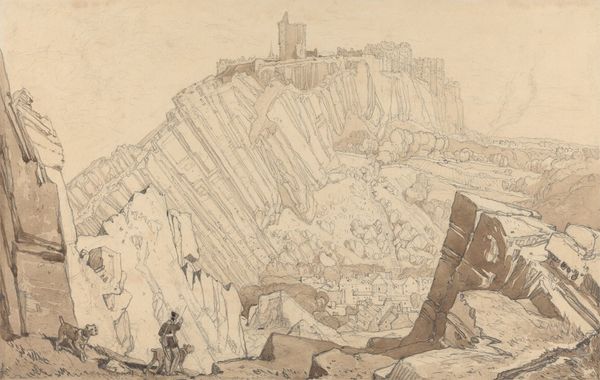

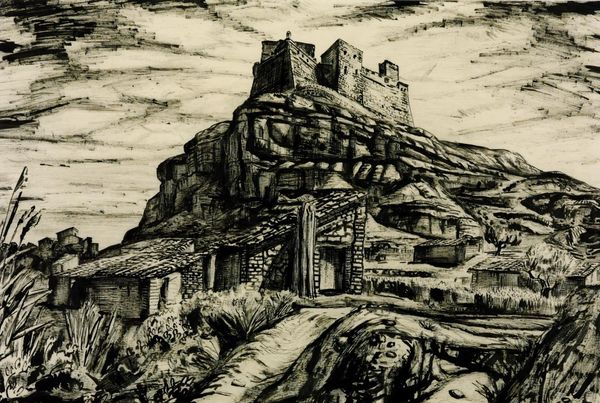

Curator: This is John Ruskin’s “Bellinzona,” a pencil drawing created in 1858. Editor: My immediate impression is one of brooding strength. The heavy lines and shadowed crags really convey the impregnability of that hilltop fortress. Curator: Yes, Ruskin was deeply invested in the visual language of power and how architecture projects it. The fortress in Bellinzona, in particular, represents centuries of shifting geopolitical forces controlling the Alpine passes. Editor: It makes me wonder about those who were excluded from that power. What stories are etched into those stones of those who suffered or died for that dominion? Curator: Well, Ruskin certainly idealized the medieval social structure that created such structures. He saw nobility in labor and order, a hierarchical system of mutual obligation he thought was being lost to industrialization. Editor: Which, of course, is a dangerous simplification. Romanticizing feudalism glosses over very real exploitation and oppression. But, I do see the appeal, I guess. It offers an imagined stability, something to hold onto in the face of massive social change. Curator: Precisely. He advocated for craftsmanship in response to mass production, seeking a moral and aesthetic ideal rooted in the pre-industrial age. Art, to Ruskin, was never just aesthetic; it was deeply entwined with social ethics. His vision aimed to counter the perceived vulgarity and alienation of modern life through a revival of Gothic principles. Editor: But can we really separate the aesthetic experience from these complex histories of power and privilege? I wonder how do we critically engage with such powerful images without perpetuating harmful ideologies? Curator: That's precisely the tightrope we must walk. Recognizing the inherent biases in historical perspectives is crucial for an informed and responsible interpretation of art. We must critically examine Ruskin's nostalgic view of the past and confront his often problematic social commentary to appreciate the work's artistry without ignoring its ideological underpinnings. Editor: I appreciate how art from the past makes us reflect upon our society and ideals. And in doing so we realize the past still has a firm hold on the present. Curator: Indeed. The intersection between art and the socio-political sphere provides critical lessons on history. Ruskin pushes us to analyze social structures reflected in such works and how they shape societal perceptions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.