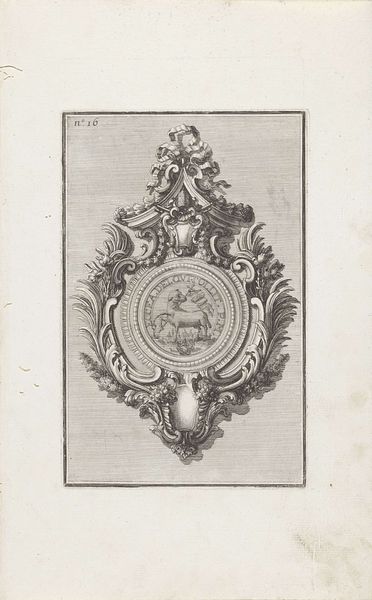

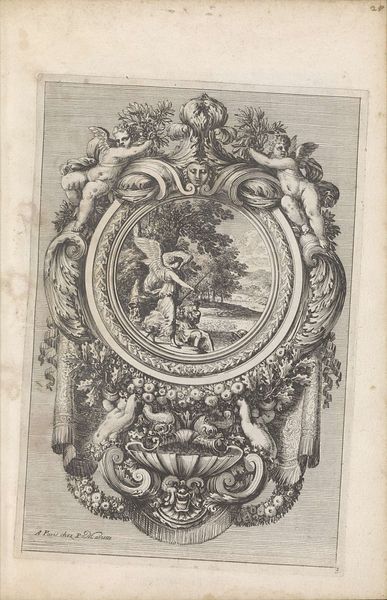

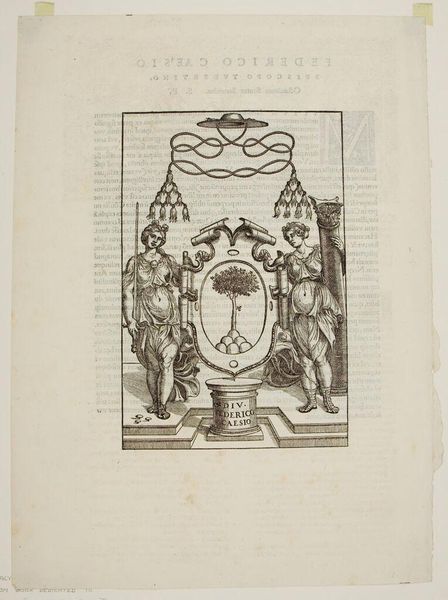

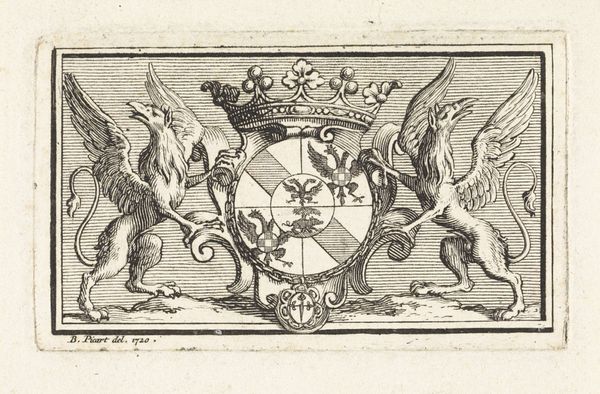

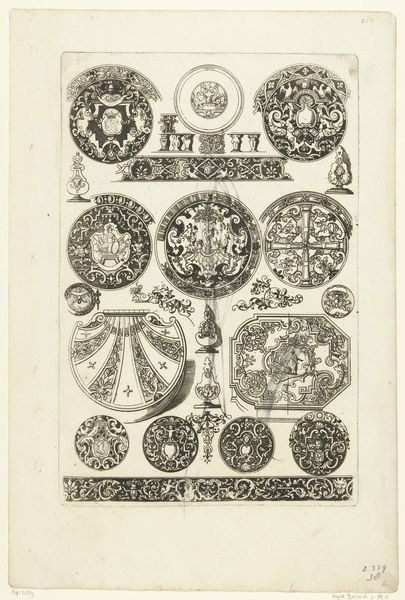

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

form

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 239 mm, width 157 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this engraving, "Ornamenten met slangen en een Medusakop," created in 1714 by Maximilian Joseph Limpach, has this intensely detailed, almost overwhelming Baroque sensibility. The snakes are so…active. What jumps out at you? Curator: Well, for me, it’s the Medusa head, hanging there like a bizarre sort of trophy. She is always staring back, isn't she? These ornamental prints often served as inspiration for artisans—imagine a silversmith, or a furniture maker, looking at this for ideas. Editor: I can totally see that. The swirling snakes around what looks like a door handle would be quite a statement piece! How would you see someone interpreting these symbols, snakes, Medusa, back in the 18th century? Curator: The Baroque period just *loved* complexity and drama, right? Medusa wasn't just a monster, but a representation of transformation, of feminine power turned monstrous and then, dare I say it, turned powerful *again.* Editor: Interesting…it's like she is warning: beauty can turn monstrous… What strikes me is the fine lines. I keep wondering, how long did it take to draw it? Curator: It makes you consider, doesn't it, the patience, and the incredible skill of the engraver. But the question also points back to what art used to *do* - which was, essentially, to instruct the public! Editor: Wow, it changed my perception. Now, when I look at this, it gives a strange, perhaps unintended lesson about skill and time. Curator: Indeed. The enduring presence of classical mythology woven into the decorative arts says so much about cultural continuity and… transformation itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.