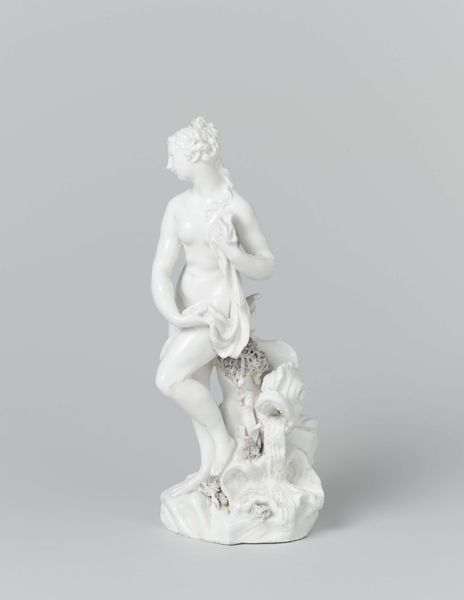

porcelain, sculpture

#

porcelain

#

figuration

#

sculpture

#

miniature

#

rococo

Dimensions: height 11 cm, width 7 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have a salt cellar in the shape of a putto, made of porcelain around 1764 by the Weesper porseleinfabriek. It’s quite small and delicate. What do you make of its production? Curator: Well, the first thing to consider is the material itself. Porcelain was incredibly sought after at this time, a luxury item largely imported. The Dutch were eager to emulate Chinese porcelain production, and Weesper was one of the early factories attempting to do so. Its presence suggests not only artistic skill but the development of industrial and chemical knowledge, doesn't it? Editor: Absolutely, but how does that affect our understanding of the object beyond its mere existence as a porcelain figure? Curator: Because porcelain manufacturing required specialized labor, each of these little salt cellars stands as a symbol for complex processes. Someone had to find the clay, someone else mix it, someone had to fire it at immense heat… We need to be cognizant of the working class infrastructure necessary to create something seemingly frivolous for an upper-class table. Does knowing the labor required change how we see it? Editor: It definitely gives it a new weight. Seeing it now, not just as an art object but as a product of intense labor... it challenges that initial sense of Rococo lightness. Curator: Exactly! Rococo is known for this ornamentation that cloaks harsh socioeconomic realities. The tension between the beautiful object and the processes of its production… it is worth considering the cost. Editor: That is insightful. I now appreciate that such pieces offer both artistry and complex stories about craft. Thanks for that fresh perspective. Curator: Of course. The tension is part of what makes this piece so intriguing, wouldn't you agree?