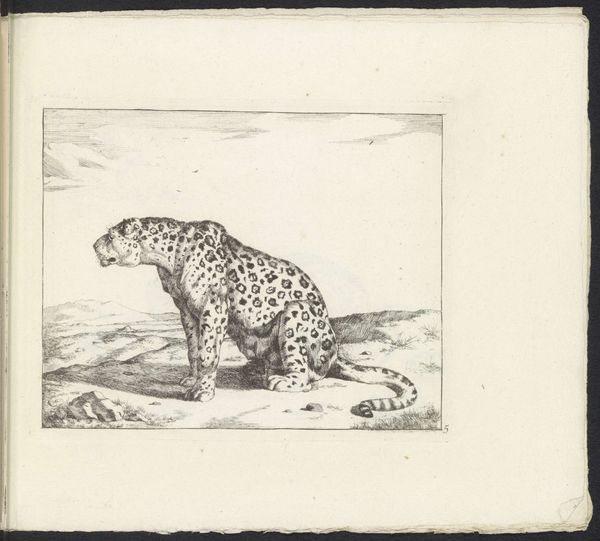

Luipaard met het hoofd van een man (mogelijk Floris Adriaan van Hall) in de woestijn naast een palmboom met tekst 1836 - 1912

0:00

0:00

isaacweissenbruch

Rijksmuseum

drawing, pen, engraving

#

drawing

#

pen sketch

#

caricature

#

old engraving style

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 104 mm, width 145 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to a pen and engraving drawing held at the Rijksmuseum, attributed to Isaac Weissenbruch. It’s titled, "Leopard with the Head of a Man (possibly Floris Adriaan van Hall) in the Desert Next to a Palm Tree with Text," and thought to originate sometime between 1836 and 1912. Editor: My first impression is a feeling of uneasy humor. The composition is odd—a human head on a leopard’s body in the desert, right next to a palm tree, etched with political…statements? The rendering has a raw, unsettling quality. Curator: It is definitely unsettling! Weissenbruch made use of accessible, inexpensive materials and methods: pen, ink, engraving... tools and skills that allowed for relatively easy replication. The means of production highlight an intent for circulation among a broad audience, not necessarily the wealthy art-buying class. Editor: Agreed. This image almost certainly functioned as political satire, aimed at criticizing Van Hall and perhaps the broader constitutional discussions of the time. The desert setting evokes feelings of desolation and perhaps exile, while the symbolic leopard suggests aggression and stealth. Who was Van Hall? What specific policies are referenced here? Curator: Floris Adriaan van Hall was a prominent Dutch politician. As for what this print references? Let’s consider the context surrounding the text inscribed on the palm tree’s fronds. We see phrases like "Constitutioneel" and names that likely indicate locations where those opposed to Van Hall have fled to, to signal discontent. Editor: It really points to a complex intersection of power, image, and dissent. It encourages the viewer to analyze the relationship between Van Hall’s actions and public sentiment, prompting discussion of governance. And that wild amalgamation of animal and human—it reflects a sense of social disruption and dehumanization, too, perhaps alluding to moral corruption. Curator: And yet, in the simplicity of the line work, we still see an artist engaging directly with the materials at hand, making pointed political commentary within the reach of a wider populace. Editor: Absolutely. Looking at it through the lens of political movements and how figures are demonized is a reminder that art has consistently served as a potent tool for societal discourse. A messy, and often ugly discourse to be certain! Curator: Well, looking at the means and process reminds us of the material conditions and accessibility of the era—pen and engraving here enabling that wider participation, regardless of social station. Editor: It seems like every little bit of what went into this drawing mattered and matters!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.