drawing, print, pencil, graphite

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

graphite

#

portrait drawing

#

realism

Dimensions: Sheet: 13 1/4 × 9 1/4 in. (33.7 × 23.5 cm) Plate: 11 3/16 × 7 3/4 in. (28.4 × 19.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

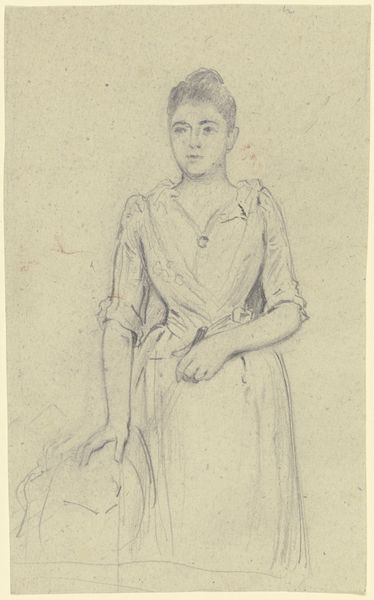

Curator: Standing before us is Félix Bracquemond's "Madame Granger, after Ingres," created in 1867. It's a graphite print, currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. What's your initial take? Editor: There's a gentleness to it, a quiet dignity. The pencil work gives it a preliminary, almost vulnerable feel. She seems poised but not particularly empowered in that tightly controlled posture, hands clasped formally. Curator: Yes, the controlled posture speaks volumes. Bracquemond masterfully uses line and space to define her form, notice the precision in the rendering of her dress, the economy of strokes that create the folds. The balance achieved with such simplicity is remarkable, and consider her soft, delicate rendering. Editor: Indeed, but thinking about the social context, one cannot help but wonder, about the expectations of women during this period and their portrayal in art. Is this vulnerability genuine, or a construct forced by societal norms? What about the power dynamics inherent in a portrait made by a man, of a woman, "after" another man? How much of this portrayal is her own presentation, or that filtered by men before her? Curator: Your points open a fascinating avenue for analysis. While acknowledging these questions, let’s also appreciate Bracquemond's technique as an etcher translating the aesthetic of Ingres. See how he captures Ingres's neoclassicism – that almost photographic clarity of line and form in printmaking. Editor: Fair, yet let’s also recall Ingres’s idealized versions of women – smoothing away imperfections, sanitizing realities. By etching "after" Ingres, is Bracquemond complicit, or is there, perhaps, an subtle critique embedded within the reproduction of that older style? Also, portraits were almost always available only for the very rich people of the moment and the gender gap always favored the exposure of men while female figures remain elusive. Curator: It seems to open space for us to view this work through different lenses; an image frozen in time, inviting continuous interpretation from diverse perspectives, doesn't it? Editor: Absolutely. This portrait, so seemingly simple, proves a potent site for ongoing questions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.