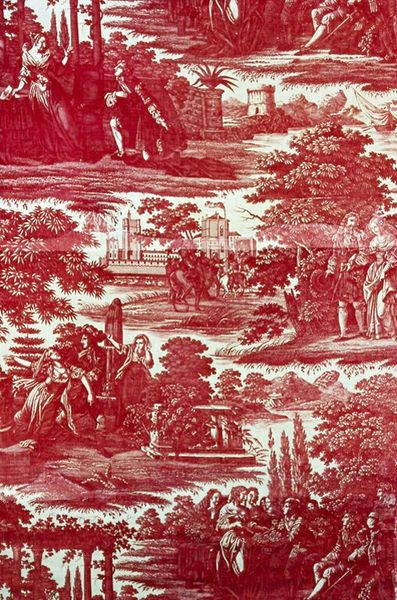

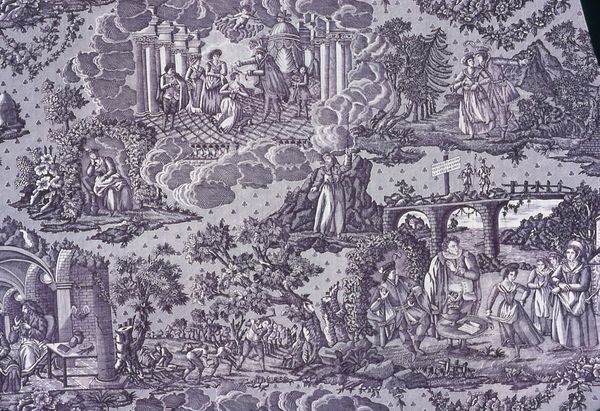

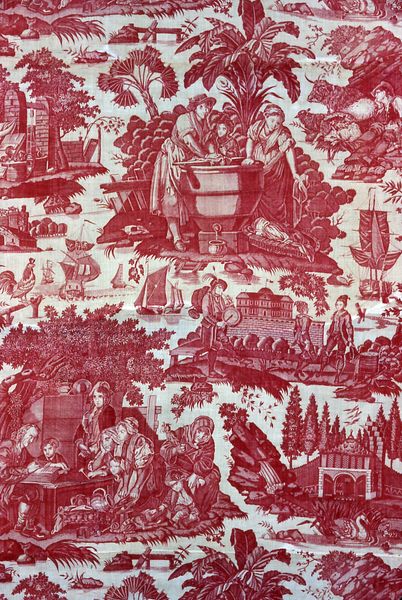

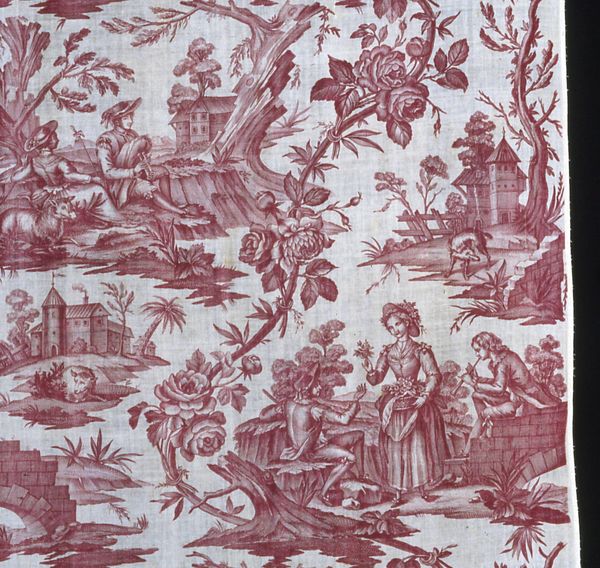

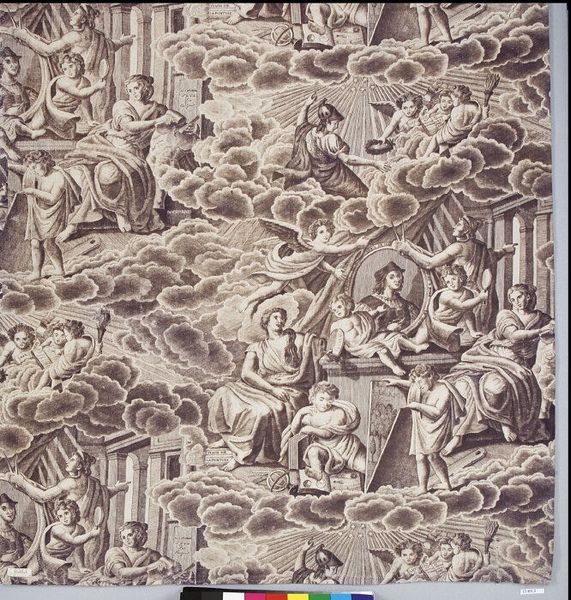

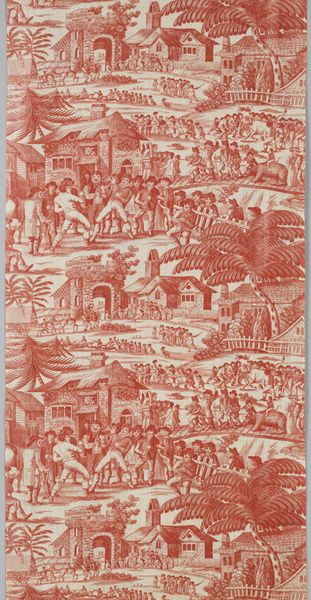

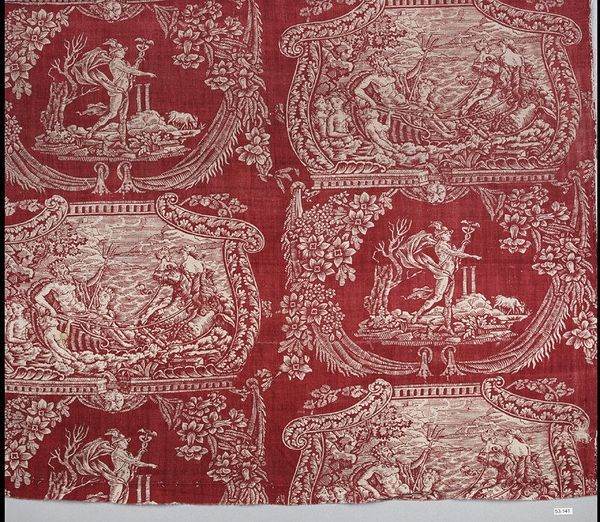

Le Char de l'Aurore (The Chariot of Dawn) (Furnishing Fabric) 1785 - 1789

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: a: 175.3 × 140.4 cm (69 × 55 1/4 in.) b: 212 × 95.2 cm (83 1/2 × 37 1/2 in.) c: 205.2 × 77.5 cm (80 3/4 × 30 1/2 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

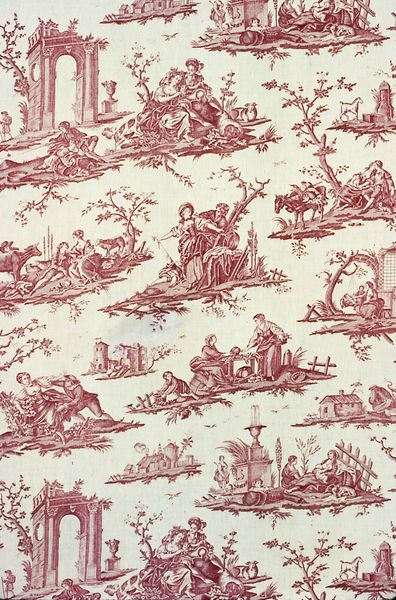

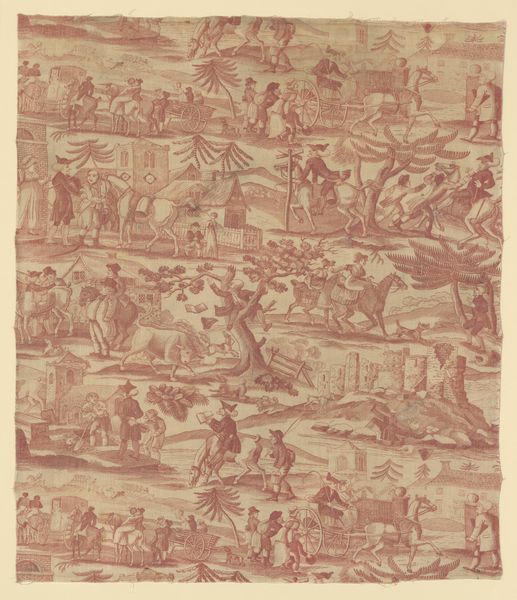

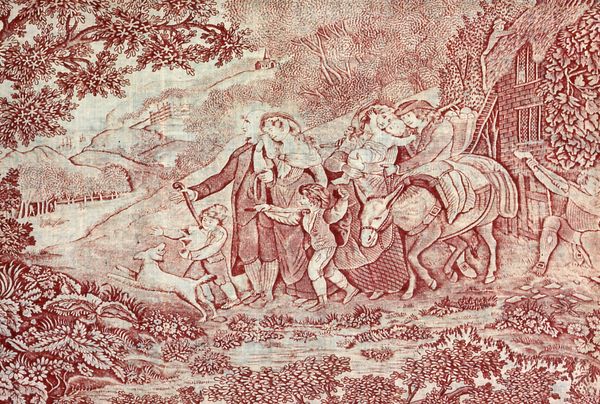

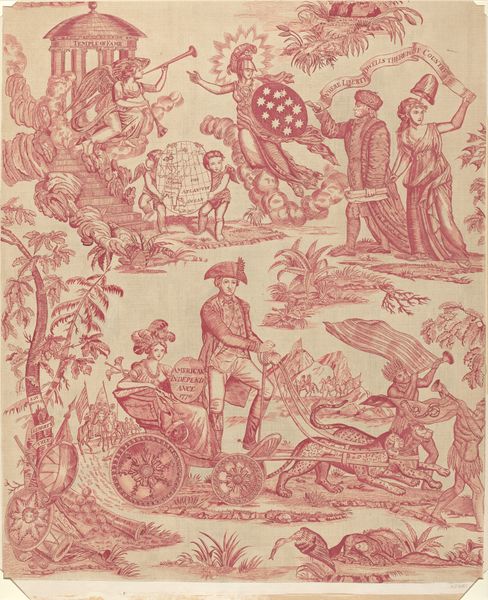

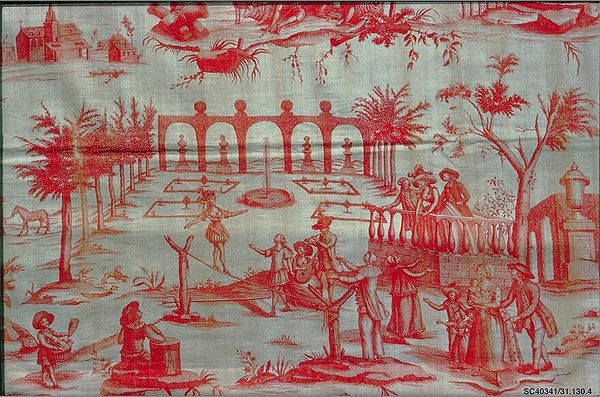

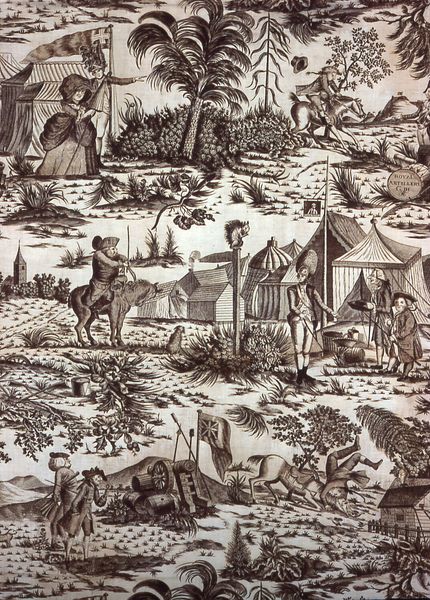

Curator: Immediately, the visual rhythm pulls me in—a pastoral dreamscape dyed a powerful crimson. It’s incredibly striking as furnishing fabric. Editor: It certainly commands attention! What we're seeing is “Le Char de l'Aurore (The Chariot of Dawn),” a textile design, dating to the period 1785-1789. It’s currently housed here at The Art Institute of Chicago, although its creator, Guido Reni, was an Italian painter of the Baroque period. Curator: Baroque on fabric… unexpected, right? And given its place within the domestic sphere, this piece engages complex class dynamics. Consider, this level of ornamentation—its pattern density, allegorical themes, likely commissioned—suggests wealth, privilege and a powerful decorative rhetoric of the late 1700s. Editor: Absolutely. Think about the means of production—weaving was highly skilled and laborious. This textile speaks volumes about labor and the value assigned to craft in relation to fine art during this historical period. It challenges those neat categorical distinctions. Curator: This artwork also participates in gendered spaces, given it was probably designed to adorn homes largely governed by women. What story could be conveyed through fabric such as this one? And what female identity did it represent? Note the narrative of Aurora—a female goddess driving her chariot into dawn... who had the privilege of seeing and owning something that explicitly spoke to these mythological tropes and fantasies? Editor: It makes me consider the source of the dyes too—were these natural pigments? What did the processing look like, and what were the labor conditions to acquire it? Textiles offer clues to colonial histories, trading networks, and hidden exploitations. The print mimics the landscape and history painting genres—again a deliberate material engagement. Curator: I appreciate that you are pushing this textile's position and presence as an historical artifact, highlighting this moment, and considering questions of who benefits and is hurt during processes like manufacturing, sales, and adornment of bodies and homes. It complicates how one reflects on this artwork today! Editor: Ultimately, an artwork like “Le Char de l'Aurore” encourages us to consider its physical construction while keeping a wider awareness about class and labor involved in its production and consumption. Curator: Exactly. We can reflect not only on the image, its allegories, and place within art history but consider deeper intersectional conversations and themes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.