relief, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

relief

#

landscape

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

figuration

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 222 mm, width 160 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

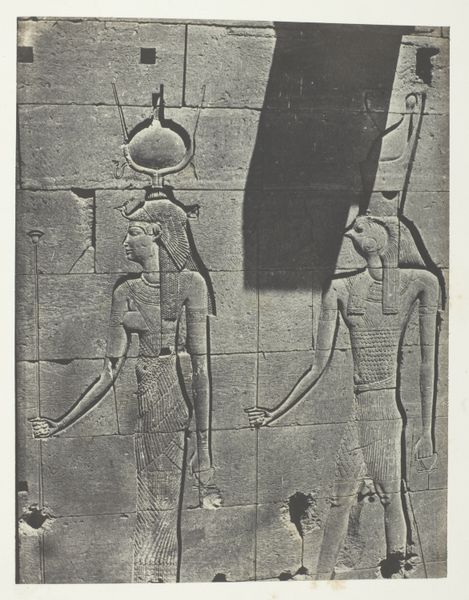

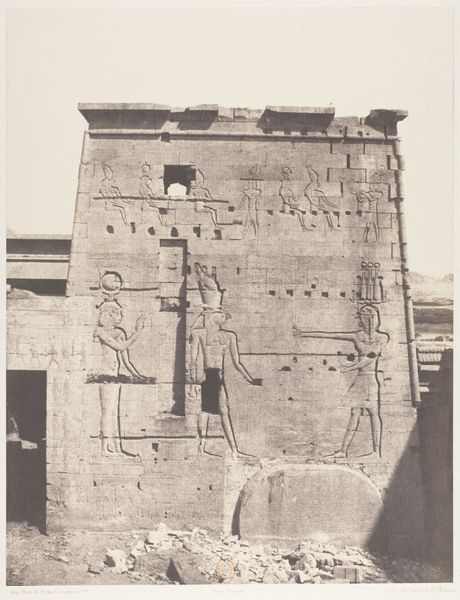

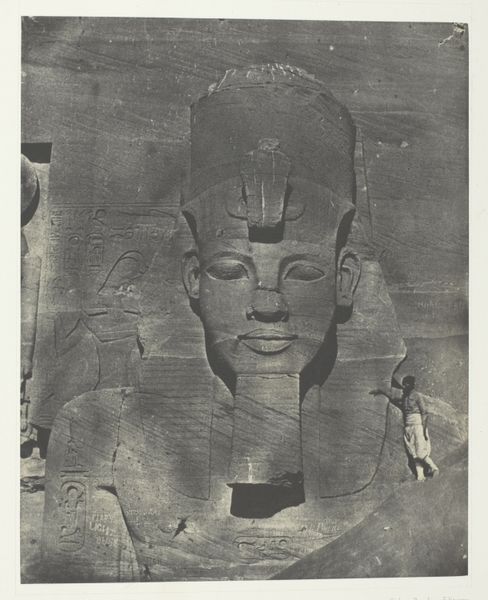

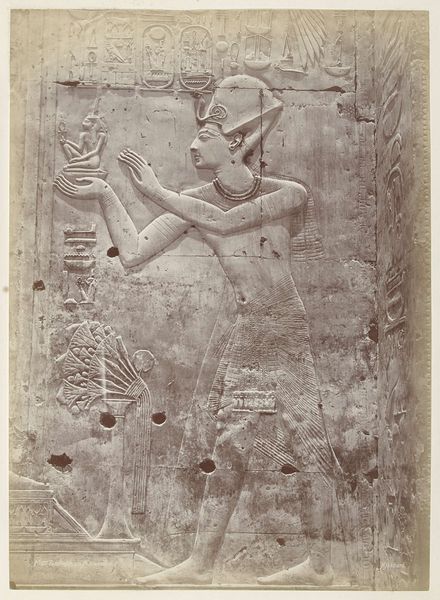

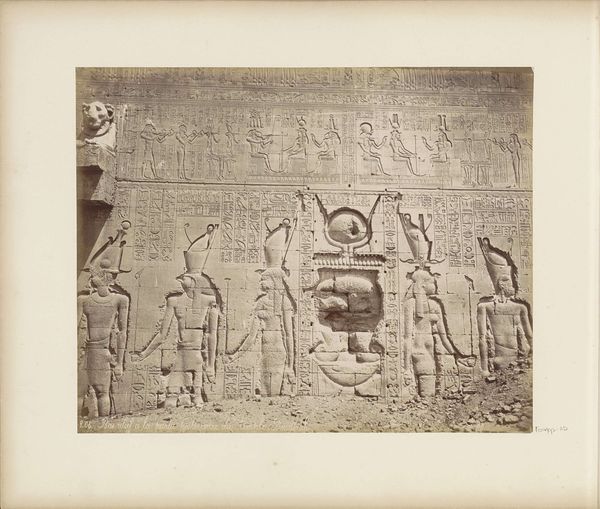

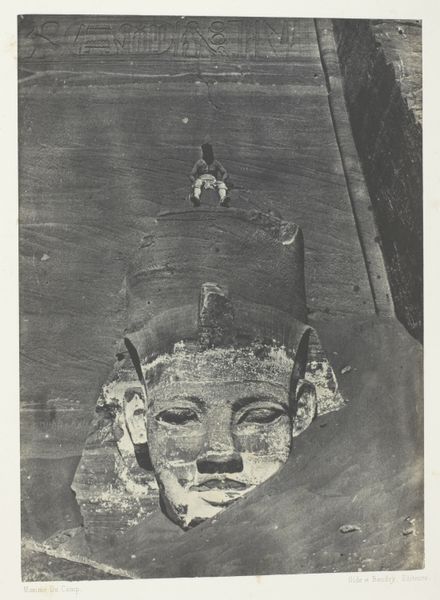

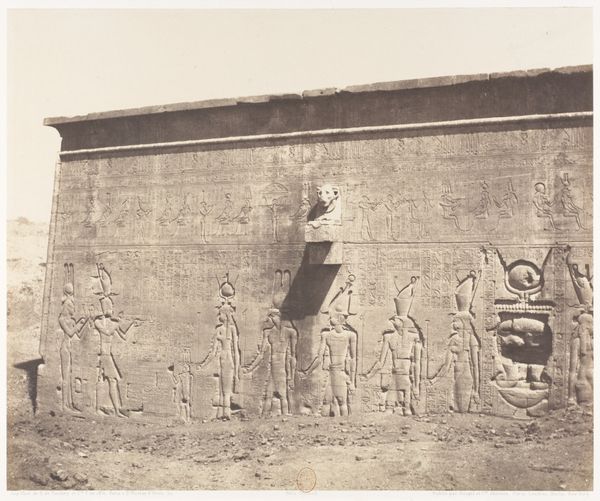

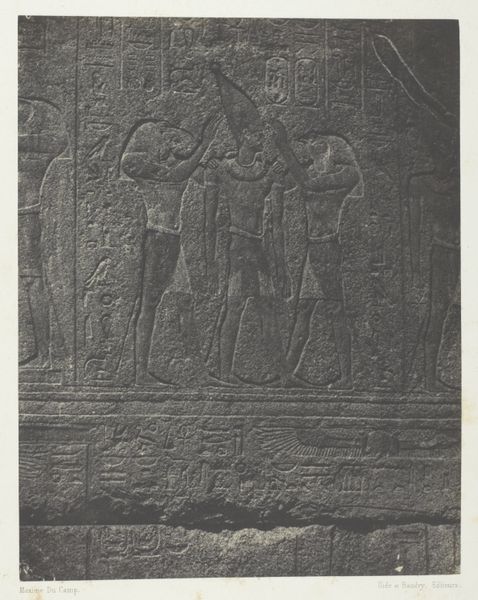

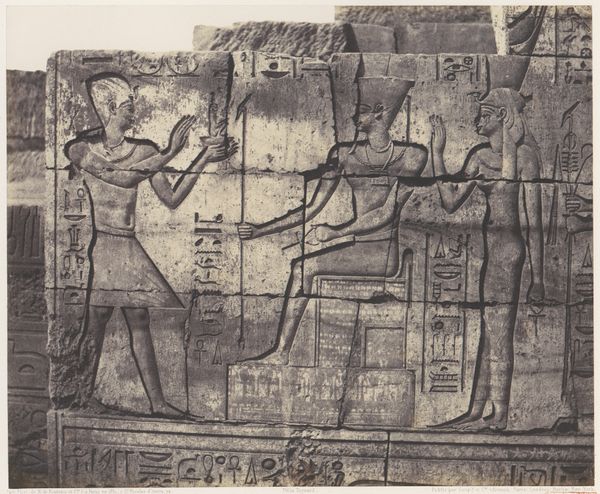

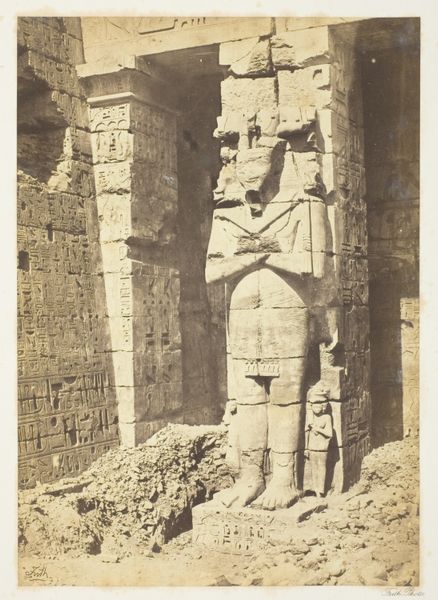

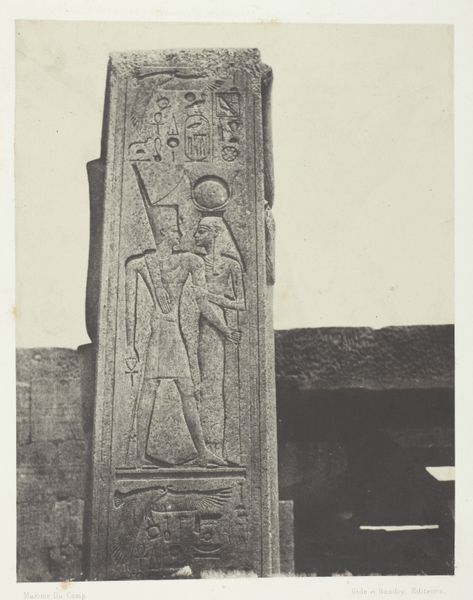

Curator: Francis Frith captured this gelatin silver print titled "Reliefs on the Island of Philae" before 1859. It's currently housed at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately striking. The monumental scale of the reliefs dwarfing the figures below—it speaks to the power structures embedded within ancient societies, doesn't it? Curator: Absolutely. And it invites questions around representation and the gaze. What does it mean to depict these ancient Egyptian deities in a medium like photography, filtered through a colonial lens? How do we interpret the photographer's role in shaping our understanding of this historical and cultural site? Editor: Thinking about materiality, I'm fascinated by the interplay between the original carved stone reliefs and the photographic process. We see light interacting with both, creating this textured surface that’s captured in the gelatin silver print. It underscores how our encounter with the past is always mediated. Curator: Precisely. And these historical photographs served to consolidate power dynamics and reinforce existing cultural hierarchies, not just offering aesthetic representation. We must ask how gender, race, and social standing impact our understanding of the labor, artistic intention, and colonial extraction happening at that time. Editor: You’re right. These figures within the image serve to heighten the magnitude. Their positioning prompts us to reflect upon the human labor involved, both in the ancient carving and in the colonial photographic expeditions of the era. What tools were available? What processes did they undergo in their practices, both physically and culturally? Curator: It’s about understanding that the image is not just a window into the past. Rather, a complicated visual artifact with its own historical and social contexts that speak directly to modern questions of intersectionality and historical narratives. The hieroglyphs are not simply aesthetic details, but convey social status, and possibly restrictions, that dictated cultural practices. Editor: Absolutely. Considering how these historical images entered collections and the networks of consumption that followed reveal another aspect of their journey through time and power. This process and Francis Frith's participation is what provides new meanings as we explore both technique and social environment. Curator: In short, exploring this image really asks us to unpack layered interactions—between art, culture, labor, and power itself. Editor: A process as enduring as the stone itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.