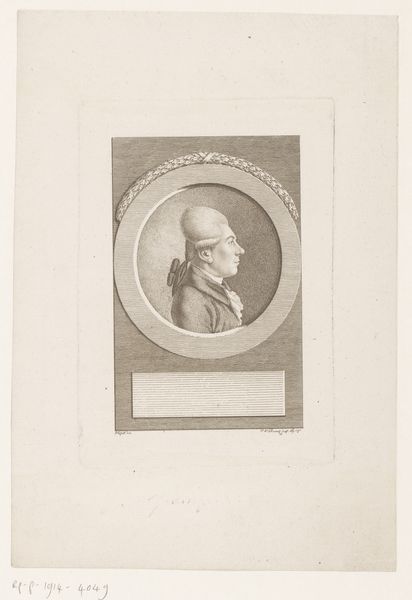

Dimensions: height 113 mm, width 94 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

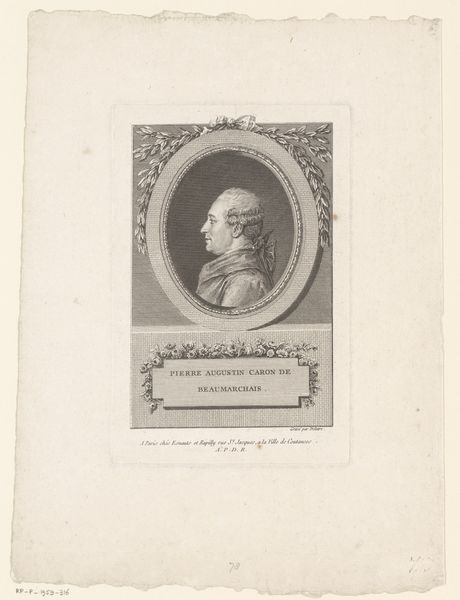

Curator: Let's turn our attention to this engraving, titled "Portretbuste van een man, mogelijk de heer L. Meister," dating roughly from 1767 to 1794. The artist is Matthias Weber. Editor: It’s quite austere, isn't it? The severe profile, the simple pedestal. There's a chill formality that I immediately perceive. Curator: It’s interesting you say that. Consider the period. These types of portraits functioned within the emerging bourgeoisie’s desire for recognition. By the late 18th century, printed portraiture facilitated broader access to representations of status and power. It mirrors social mobility during a period of revolution and intense political debates about representation. Editor: True. But I still see a constraint, almost a deliberate muting of emotion. I wonder about Meister himself. Was this how he wanted to be seen, a sort of controlled image for public consumption? Curator: Or how he was allowed to be seen. These commissioned portraits played a critical role in crafting identity and communicating ideals within the patriarchal power dynamics of the time. We might also question how class influenced expectations surrounding representation and the sitter's power. Editor: Right, and maybe we are projecting too much of our own contemporary views on to it. Still, what do you think this reveals about ideas of masculinity then? The lack of embellishment seems deliberate. Curator: Absolutely. This understated depiction becomes, ironically, its own form of power statement. The meticulous rendering would communicate the sitter's refinement. It's a specific performance, carefully orchestrated. Consider how that contrasts to artistic movements which resisted these forms. Editor: Well, viewing it now, in our particular moment, I see both the inherent constraint, and perhaps, a quiet act of resistance too. He looks directly outward and slightly upward – maybe that upward gaze implies hope? Curator: It prompts one to question who ultimately controlled that gaze. Whether by artist’s direction, or sitter’s ambition, these nuances reveal intricate facets of their relationship and the very art of image making. Editor: It's amazing how a seemingly simple portrait can open up so many questions about societal structure and individual expression. Curator: Exactly, and its presence here, its history, now woven into its very fiber invites these conversations and critical readings that makes the artwork vibrant, enduring, and deeply relevant.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.