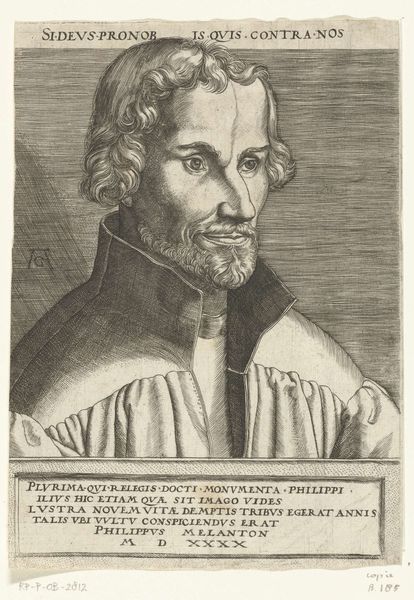

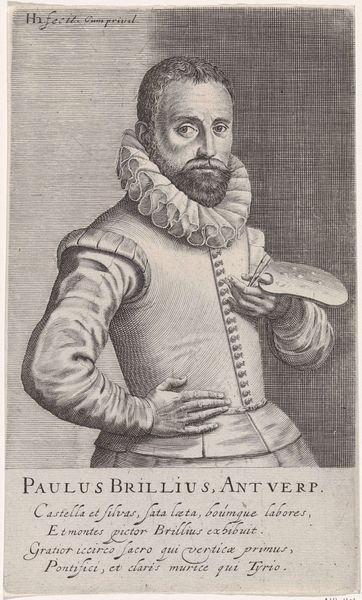

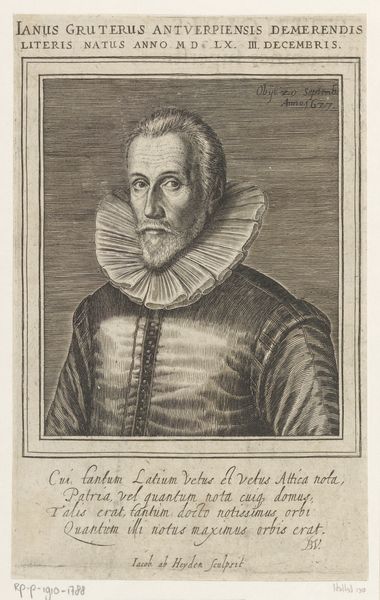

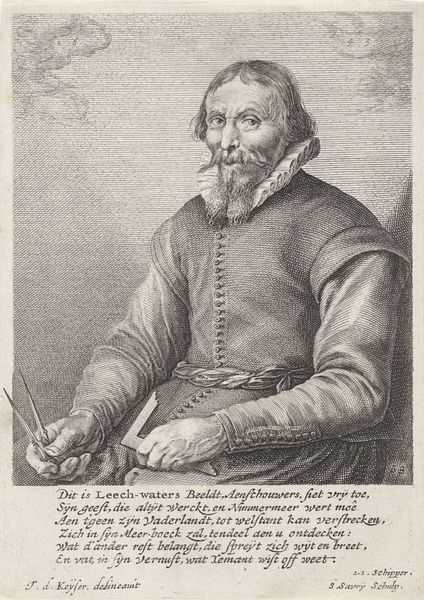

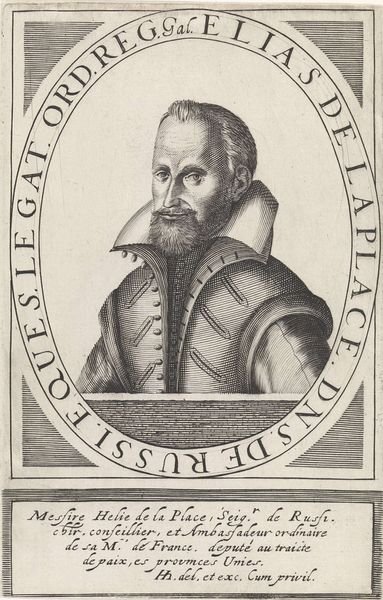

metal, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

metal

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 177 mm, width 113 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Portret van François de Loberan de Montigny" by Melchior Tavernier, an engraving that seems to date from sometime between 1619 and 1641. It's quite detailed for its medium, and the subject has a very self-assured expression. What strikes you about this portrait? Curator: What grabs my attention is the interplay between individual agency and imposed societal structures that's embedded within its visual language. Engravings like these weren't simply about likeness; they were strategic tools in shaping and reinforcing aristocratic power structures. Editor: Can you elaborate on that? Curator: Consider the inclusion of the heraldic crest. It is a blatant declaration of lineage and status, isn’t it? These symbols operated as visual shorthand, instantly situating Montigny within a specific network of privilege and obligation. Ask yourself, what message is Tavernier crafting for his intended audience? Editor: So, it's not just a portrait, but a statement about belonging to a certain class? Curator: Exactly. But we can push that further. Think about the context of the Baroque era. Religious and political turmoil was frequent at that time. These displays of wealth and status were a way of asserting dominance and control in a world that was constantly changing and challenging old orders. Even the choice of engraving, a medium that allowed for mass reproduction, points to a desire to disseminate this image and, by extension, Montigny’s authority widely. It seems intended to project strength but doesn’t it strike you that his gaze seems almost weary? Editor: That's true, I hadn't noticed it before. So much is being said with just one image. Curator: Indeed. By deconstructing these layers, we reveal not just a portrait of an individual, but a complex tapestry of power, identity, and representation deeply intertwined with the sociopolitical climate of the 17th century. Editor: This has made me look at portraiture in a whole new way; thinking about what power structures they reinforced or challenged. Curator: Precisely. Art provides this sort of access to critique culture and historical events in many ways.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.