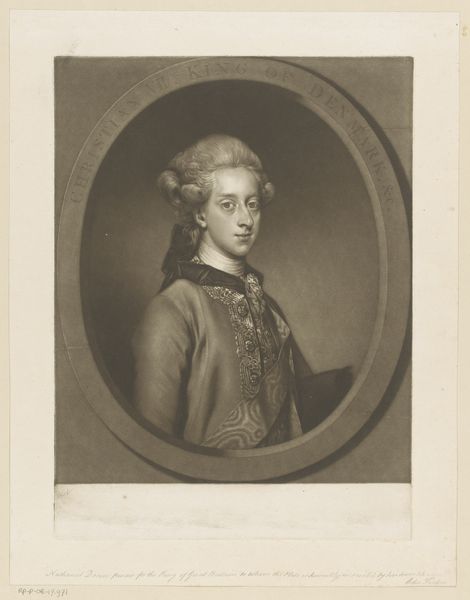

Portrait of Madame du Barry, after Drouais 1760 - 1790

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: Sheet: 9 3/8 × 12 9/16 in. (23.8 × 31.9 cm) Plate: 8 3/4 × 11 15/16 in. (22.3 × 30.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is an engraving, "Portrait of Madame du Barry, after Drouais," created sometime between 1760 and 1790, made after an image by Jacques Firmin Beauvarlet. It’s currently residing here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: There's a haunting delicacy to it. Even in monochrome, you sense the softness of the sitter's gaze and the elaborate textures of her clothing. I find it evokes a sense of faded grandeur. Curator: Absolutely, it’s a window into the Rococo period. Madame du Barry, the subject, wasn’t just any noble; she was the last official mistress of Louis XV. The artist masterfully captures that period's essence: the powdered hair, the intricately detailed dress. Each element tells a story of privilege, style, and social standing. Editor: Yet, knowing her history—a woman from humble beginnings who rose to immense power, then met a brutal end during the Revolution— I find this portrait profoundly unsettling. The oval frame becomes a cage of expectation. The very "historical fashion," feels less about beauty and more like an oppressive social code. Curator: That’s a powerful point. Frames always carry an evocative feeling of being captured or held in space. However, the artist seems to present a narrative more entrenched in classic portraiture tropes. We can trace these symbolic links all the way back to classical representations of the idealized feminine, later associated with nobility. I find it impressive how this engraver managed to render the complex layers of silk through varied engraving patterns. Editor: True, the technique is remarkable. But even in the artist's skillful rendering, I see a commentary on the objectification inherent in depicting women for consumption. Look at how much visual information is dedicated to surface details while the emotion feels... suppressed. Isn’t she just the ultimate symbol of the excess that fueled revolutionary fervor? Curator: Perhaps that very suppression reflects the limitations imposed upon women of the court. It's as if her expression holds the weight of unwritten rules and unspoken expectations. But more interestingly, isn't she part of a wider symbol set: beauty, royalty, art itself? Even revolution doesn’t erase the symbols completely. Editor: Yes, those symbols continue to haunt and shape us. Ultimately, examining this portrait helps me consider what truly shifted and what stubbornly remained unchanged by revolutions, be they social, political, or artistic. Curator: A great consideration. Reflecting on the artistic approach through history always allows new angles, in terms of symbolic meaning and in terms of technique.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.