print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

figuration

#

engraving

Dimensions: 168 mm (height) x 105 mm (width) (bladmaal)

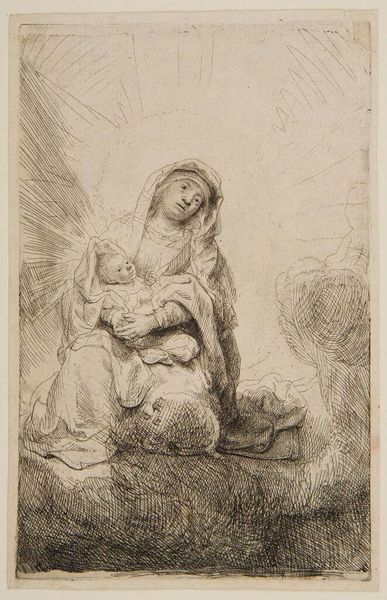

Curator: Let's examine "Virgin and Child in the Clouds," an engraving completed in 1641 by Rembrandt van Rijn. What strikes you upon seeing this piece? Editor: The starkness. There's a vulnerability to it. It isn't idealized. There's a real sense of the maternal here, but one burdened by worldly cares, by a distinct lack of divine support, almost like a Madonna of the everyday. Curator: I appreciate how you immediately draw attention to the figures' relationship, but also how you perceive that through their formal construction: notice the linear network; a very carefully structured arrangement where the composition’s tonal unity brings our eye to the figures, and allows us to interpret the mood as one of earthly realism instead of heavenly opulence. Editor: And I can't help but wonder if that was intentional given the political and religious tensions in the Dutch Golden Age. Is Rembrandt perhaps commenting on the Catholic view of the Holy Mother, humanizing it for a Protestant audience? What do you make of the radical departure from typical depictions of the Madonna at that time? Curator: I don't find any real "radical departure." Instead, it reads as the work of a master engraver concerned, like many others, with mastering perspective, line and form. While context matters, reducing it to a mere religious statement overlooks his meticulous engraving technique, the texture he creates. His command of the medium itself conveys so much of its meaning. The composition of chiaroscuro is perfectly executed, look how strategically Rembrandt manipulated shadows to imbue the image with depth, further highlighting the formal relationship. Editor: But what if that use of light and shadow is purposeful for social critique, showing a contrast between ethereal belief and lived experience? Can we ignore that the Protestant Reformation challenged elaborate Catholic iconography and created space to showcase the human aspect? Curator: We seem to perceive distinctly disparate aspects of the work. Yet I find in the visual structures themselves a powerful evocation of harmony through the perfect use of graphic articulation. I find a testament to Rembrandt's craft. Editor: And I find that those articulations provide insights into 17th century perspectives of gender, religion, and daily life. Art isn't just an image, but an invitation into nuanced discussions of what matters.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.