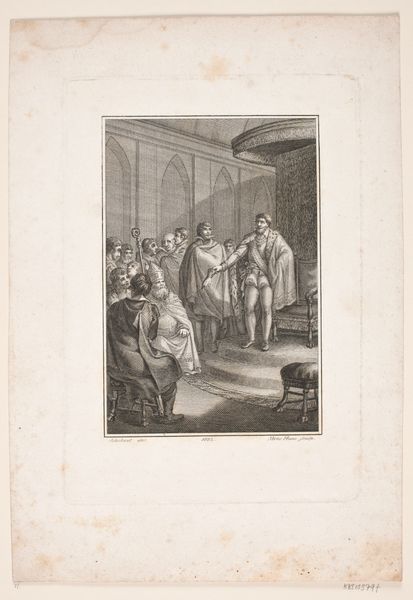

Dimensions: Plate: 7 11/16 × 9 9/16 in. (19.6 × 24.3 cm) Sheet: 8 7/16 × 10 3/16 in. (21.5 × 25.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

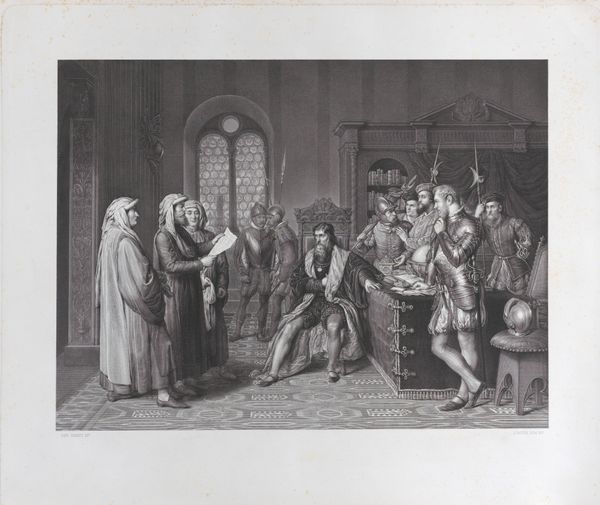

Editor: Here we have William Nelson Gardiner’s "Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots," a print from 1790 made using etching and engraving. It's a stark depiction, of course, and the use of line and shading really emphasizes the brutality. What stands out to you about the piece? Curator: For me, it’s about the means of production. Engravings and etchings like this weren’t just artistic statements; they were methods of disseminating information, of manufacturing consent, even. Think about the labor involved in creating these prints, the materials – the metal plates, the inks. And the context: prints like this were consumed en masse. How does this image of a queen's execution shape popular understanding and reinforce social power? Editor: So it's less about the artistic merit, and more about its function as a manufactured object? Curator: Precisely. Consider the inscription beneath the image: it's clearly designed to generate a very specific reaction. Who are the consumers, who is meant to witness and revel in the execution? And further, how might different production choices affect how that image functions culturally? If it were a painting, or a sculpture, what would change? Editor: That makes me consider who might own something like this and what its display might signify? I never thought about this type of image having different value based on who is consuming. Curator: Exactly. By focusing on the process, we can uncover hidden social and political messages embedded in seemingly simple images. This redefines the boundaries between art and… propaganda. Editor: That’s a fascinating way to reframe this. I will never look at etchings the same again. Thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.