drawing, plein-air, paper, pencil

#

drawing

#

16_19th-century

#

plein-air

#

landscape

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

hudson-river-school

Copyright: Public Domain

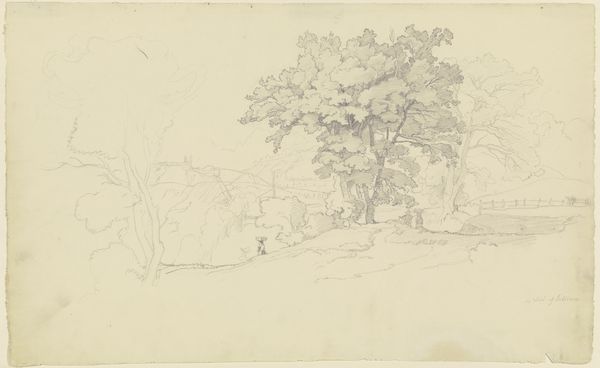

Editor: So, this is Johann Wilhelm Schirmer's "Chestnut forest near Kronberg," a pencil drawing on paper from the 19th century. There's a real softness to the rendering, almost like looking at a dream. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see a direct engagement with nature that goes beyond a purely aesthetic appreciation. It makes me think about how access to landscapes like this has historically been stratified, often reflecting power dynamics related to land ownership and social class. Think about who was allowed to freely wander and represent these spaces. Editor: That's interesting. I hadn't considered it in terms of access. Does the "plein-air" aspect, the fact that it was made outdoors, have significance then? Curator: Absolutely. The act of drawing *en plein air* in the 19th century becomes a statement. The artist, presumably male and likely from a privileged background, positions himself within a tradition tied to certain societal structures. But then, we have to consider the *nature* of that engagement. Is he observing? Is he reflecting a particular Romantic ideology that serves a certain demographic? What narratives are being reinforced or challenged? Editor: So it's not just about a pretty picture, but who had the privilege to even *make* that picture and what they might be saying, consciously or not? Curator: Precisely. And who was excluded from that narrative. This forest isn’t just a place, it's a representation shaped by cultural forces. It raises questions about environmental stewardship and its relation to issues of social justice, and perhaps it encourages us to consider whose stories aren’t being told about these landscapes. Editor: It definitely gives me a lot to think about beyond just the artistic technique. It's a call for contextualisation. Thank you. Curator: Indeed. Every landscape carries not only trees and light, but a history of human interaction. That perspective encourages a far more inclusive art history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.