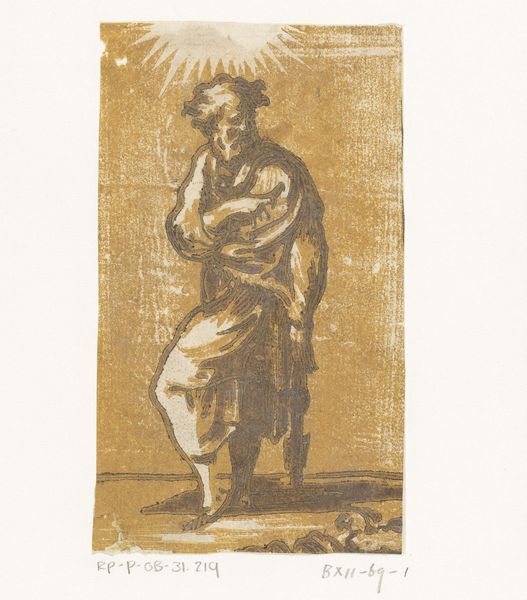

print, intaglio, engraving

#

portrait

#

ink drawing

# print

#

intaglio

#

etching

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 124 mm, width 70 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Standing before us is "Heilige Simon" by Antonio da Trento, dating from around 1520 to 1550. It’s an intaglio print, rendered with etching and engraving. Editor: The figure seems caught between shadow and illumination. He holds what appears to be a saw aloft. The use of line creates a tangible tension; it’s powerful for something so small. Curator: The subject is Saint Simon, one of the twelve apostles, and patron saint of tanners and sawmen. Notice his attribute—the saw, alluding to his martyrdom. His pose reflects a common approach for depicting religious figures. The choice of such subject mirrors how art, particularly prints, helped disseminate religious stories. Editor: I am intrigued by that very saw. Held aloft, it almost seems to be emitting light. Simon’s expression suggests acceptance and perhaps triumph. Given he holds the symbol of his death, there is a rather paradoxical feel of both suffering and resolve that emerges here. Curator: These prints served purposes both devotional and didactic. Think of how a print like this would have functioned in private worship or teaching the illiterate about key religious figures. Da Trento was a key figure of the printmaking circles. Editor: Looking at this as an emblem of the time, is that the print transforms suffering and death into an inspirational vision. One could find courage and comfort through this representation of their faith during times of unrest or uncertainty. Curator: Certainly. And we can’t underestimate the market aspect; there was high demand in 16th century Europe for accessible imagery of revered saints. This reflects, too, how printing helped standardize representation; images, disseminated across a continent, began to define a more uniform visualization of the saint and stories of his life and faith. Editor: That shared visual culture gives symbolic meaning even more power; one can begin to see the threads tying different regions together. It also offers continuity to an understanding that can outlast its time. Curator: Absolutely. Looking closely at it reminds us how vital religious imagery was—not only spiritually, but socially and even economically, in the early modern period. Editor: To study its symbolic resonance is to come closer to an understanding of people, the things to which they gave value, the ways in which they saw and told stories about their place in the world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.