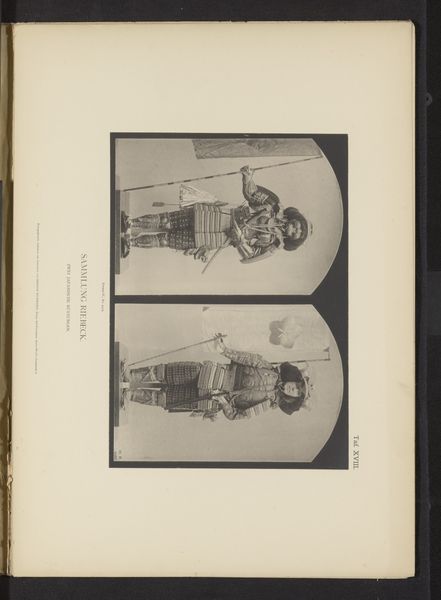

Portret van vijf Limbu krijgers uit Nepal in strijdkleding met wapens before 1868

0:00

0:00

photography

#

portrait

#

ink drawing

#

photography

#

group-portraits

Dimensions: height 151 mm, width 209 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

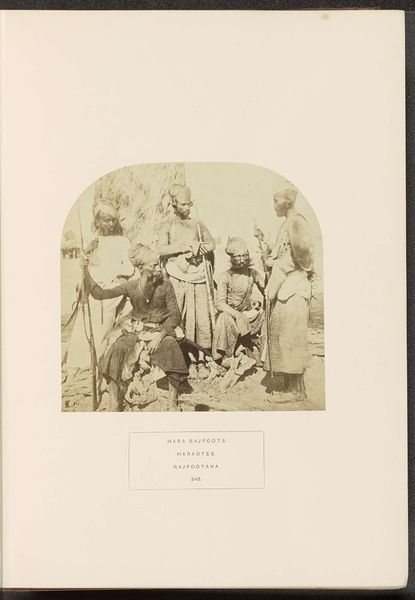

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to a striking image—a daguerreotype from before 1868 by Benjamin Simpson. It’s titled "Portret van vijf Limbu krijgers uit Nepal in strijdkleding met wapens"—"Portrait of Five Limbu Warriors from Nepal in Battle Dress with Weapons." Editor: Immediately, I notice the light. It's uneven, almost theatrical. It makes me wonder about the physical process of capturing this image. The long exposure must have been a challenge for these men to hold still, fully adorned. Curator: Indeed. The photograph offers us a glimpse into the visual culture and martial traditions of the Limbu people of Nepal. Look at the detail etched into their clothing and weaponry. These aren’t merely functional objects; they are powerful signifiers. The weapons themselves become symbolic extensions of the men. Editor: I agree. I’m fascinated by what the materials tell us. Are those locally sourced metals in their knives? The textures of the fabrics suggest homespun techniques, but there's also a military structure, some uniforms that clearly mark rank or role. How does that speak to trade, empire and colonial exchange in materials at the time? Curator: Precisely. And think about what these specific garments and weapons meant within Limbu society—how they represented status, bravery, and a connection to ancestral traditions. The daguerreotype would be both documentary and deeply symbolic. The vertical weapon carries both connotations, suggesting virility, authority and military power. Editor: I also see the setting: a photographer's studio versus natural terrain. Simpson perhaps positioned these figures according to colonialist conventions or demands about representing them in relation to "western" ways of dress. How does it complicate this reading of traditional life? The photograph's making transforms how their identity becomes a commodity for cultural consumption. Curator: An excellent point. The act of photographing itself shifts the image into a statement about power and representation—a meeting of cultures, if you will, with all the inherent imbalances. These choices made by the photographer construct a particular idea that’s intended to communicate with audiences back home. Editor: So true. I look at this and am reminded of how photography transformed cultural understanding, but also reified stereotypes through the control of lens, labour and medium in visual culture. Curator: Thinking about these layers definitely provides a much richer appreciation for this photograph, doesn’t it? Editor: Absolutely, I agree! It’s not just a record, but evidence of social dynamics as a photograph of objects, subjects and practices for global audiences.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.