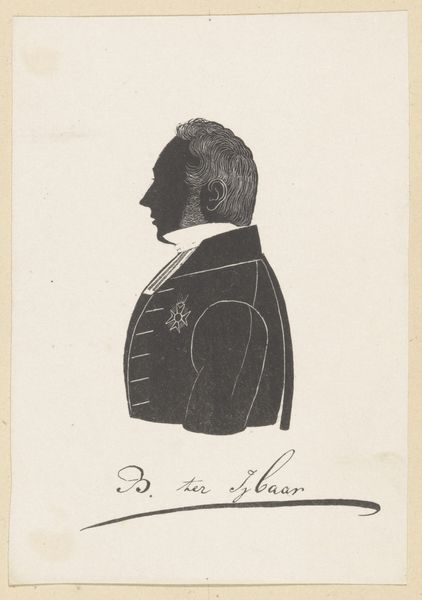

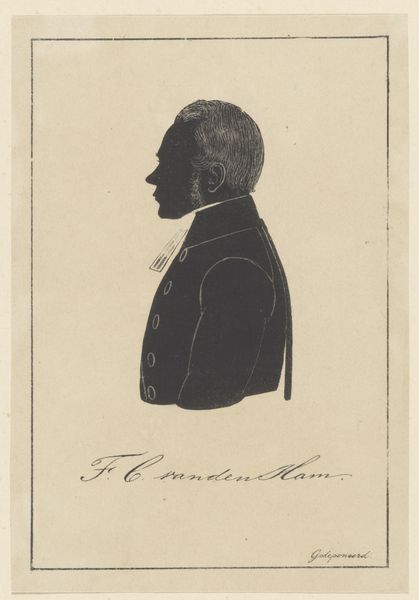

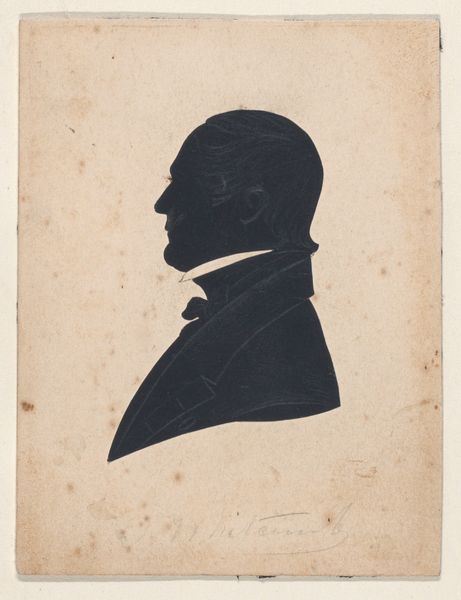

drawing, paper, graphite

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

old engraving style

#

caricature

#

figuration

#

paper

#

historical photography

#

romanticism

#

line

#

graphite

#

academic-art

Dimensions: height 150 mm, width 107 mm, height 275 mm, width 220 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us, we have a striking silhouette portrait of Bernard ter Haar, crafted by Pieter (IV) Barbiers between 1809 and 1848. It's rendered in graphite on paper. Editor: The immediate impression is one of stark simplicity. The clean lines create an almost severe formality, despite the diminutive scale of the work. It really emphasizes the sitter’s silhouette, distilling his essence down to these stark shapes. Curator: Silhouette portraits were, in some ways, the Instagram filter of their time. Accessible to a wider segment of society, compared to painted portraits, they provided a means of documenting one's likeness. Considering Bernard ter Haar’s work as a theologian and writer, it speaks to a burgeoning middle class eager to participate in a visual culture previously reserved for the elite. Editor: It’s fascinating how Barbiers uses line to define texture and form, particularly in the hair and the lapel of the jacket. The very absence of color enhances the geometrical nature of the piece. See how the row of buttons creates an almost musical rhythm down the figure's front. Curator: Absolutely, and in studying Ter Haar, it’s hard not to consider the sociopolitical implications. Here’s a figure involved in shaping religious thought, presented without fanfare. It suggests a certain modesty, yet also a self-assuredness fitting someone of influence during a period of significant social and religious change. It makes one think about the rising tide of intellectualism amidst the backdrop of post-Napoleonic Europe. Editor: I'm particularly struck by how the empty space around the silhouette becomes as important as the form itself, delineating the precise contour and enhancing the sense of depth despite the lack of shading. This conscious arrangement allows us to reflect on what the artist chose to emphasize—the shape, the line, the form, all contributing to a statement about identity and representation. Curator: What began as a simple method for portraiture allowed for democratization, offering more people the opportunity to partake in self-representation. And in turn, the rise of images like these helped shift understandings about class and identity. Editor: Ultimately, what’s left is this indelible image of a man, captured through shape and form. An insightful glimpse, wouldn't you agree?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.