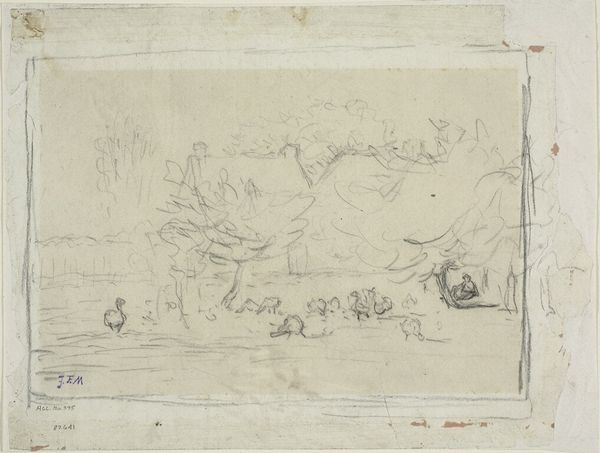

drawing, ink

#

drawing

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

ink

#

orientalism

Dimensions: height 24.0 cm, width 20.0 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's take a look at this drawing, titled "Landschap," created sometime between 1850 and 1900 by the artist Cheng Men. It's an ink drawing depicting a stylized landscape, evocative of Asian art traditions. Editor: It strikes me as delicate, almost ephemeral. The sparse ink lines give it a sense of lightness, and the scene itself, with the bridge and flowing water, feels quite tranquil. Curator: That tranquility speaks to a very deliberate construction, echoing Orientalist tropes that had begun circulating globally. What appears 'natural' belies carefully crafted representations of idealized landscapes, reflecting and reinforcing existing colonial power structures and ideas about Asia. We must be aware of this framing. Editor: Absolutely, but thinking about the process – the deliberate choices involved in selecting the brush, mixing the ink, and the skill needed to achieve this economy of line – I find that very compelling. It suggests a particular type of labour and an intimate relationship between the artist and the materiality of the work. Also how different might these materials have been created through labour? Curator: The flowing water, the bridge...these weren't simply neutral elements. They carried symbolic weight related to journeys, transitions, and a connection to nature heavily steeped in ideology and spirituality of the time. It's crucial we unpack these visual cues and understand how they worked to shape perceptions. Who could enjoy nature at that time? Editor: And considering the small scale of the drawing itself, the impact becomes even more nuanced. It becomes portable, easily disseminated, furthering that image of a carefully mediated 'East' for Western consumption, as well as the consumption habits back East. The relationship between production, consumption and labour has some profound effects. Curator: Right. The landscape isn’t just a place, but a carefully manufactured idea shaped by and perpetuating colonial discourse, which speaks volumes about intersectional power dynamics during the period. Editor: Examining the process, its delicate creation by hand, alongside the reproduction speaks to the power that materiality holds. We cannot examine the artwork through aesthetics alone. Curator: Precisely, to truly understand a work, we must be alert to its historical construction, ready to dissect and interrogate every detail to unravel what this landscape means within a complex network of power, identity, and representation. Editor: Yes. It's important to remember that this landscape, however aesthetically pleasing, speaks to an involved historical context between consumer, artist and subject that speaks more volumes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.