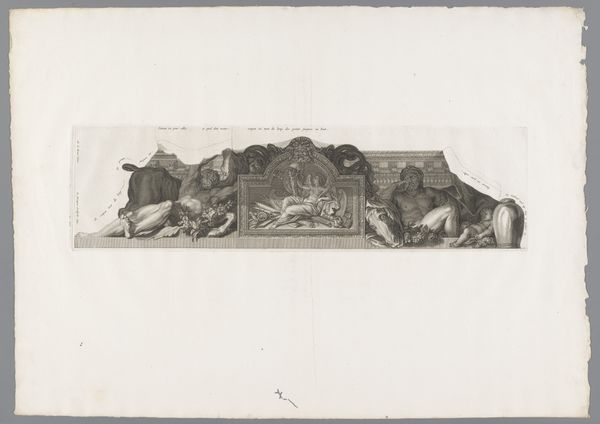

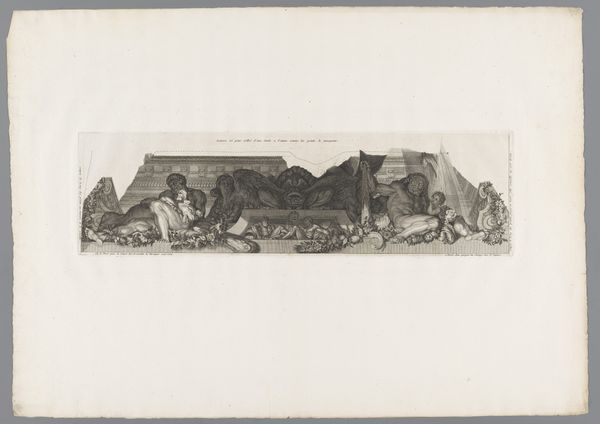

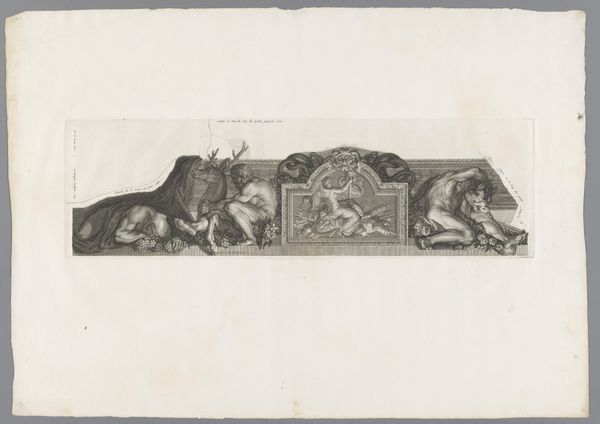

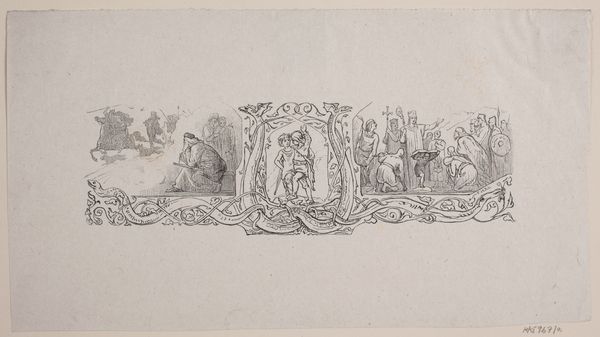

Reliëf geflankeerd door Hercules met de hydra van Lerna en Hercules met de Nemeïsche leeuw 1713 - 1719

0:00

0:00

bernardpicart

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

baroque

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 170 mm, width 566 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: So, here we have "Relief flanked by Hercules with the hydra of Lerna and Hercules with the Nemean lion," a print made by Bernard Picart sometime between 1713 and 1719. The medium is listed as ink on paper, an engraving, and it resides here at the Rijksmuseum. My immediate question is, what raw materials went into making the ink, the tools to make the impression and print this work? Editor: Hmm, first glance? It's pretty dramatic. Hercules battling beasts? I feel a sense of, well, muscular overwhelm! All that power straining within such carefully controlled lines. It makes me wonder about the guy, Picart—did he feel like he was wrestling with something too? Curator: Interesting to jump straight to biography but focusing back on production we can consider how a copper plate is acquired. The tools to etch the line into the plate themselves. The labour process of drafting the relief, translating the bodies. Where were the economies of scale that influenced the price, who purchased prints like this and in what social environments? Editor: Good points! But looking at the figures…there’s this air of Baroque drama, all swirling movement trapped in print. Makes me think, what story was Picart trying to tell? Hercules embodies heroic strength, right? But positioned around the relief, maybe it implies something about art, maybe it frames its burdens—almost crushing him? Curator: Let's consider the context. These mythological figures weren't merely decoration. They symbolized power, virtue, and often, the patron's aspirations, the act of artistic creation a production of political authority too. How might those original receivers of these printed materials understood that encoded labour power to see its subject and tell stories of the receiver? Editor: A loaded question for a loaded composition! To me it is like he used the ink, the print, the materials, all as weapons—subtle ones, granted—to hint at a more complicated truth about power, strength and artistry, the heroism that has to perform for the spectator versus that figure burdened, tired, by their labors! It is nice when it can be boiled down to simple binary. Curator: So from a Materialist point of view it is the production and historical circumstances that tell us that the powers these classical images signified was also material reality to a large segment of the early eighteenth century audience. Editor: For me, thinking about what these heroes tell me personally and what those original decisions say to our shared experience is a way to find deeper shared connection with artwork through creative expression!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.