drawing, coloured-pencil, tempera

#

drawing

#

coloured-pencil

#

narrative-art

#

tempera

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

coloured pencil

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

watercolor

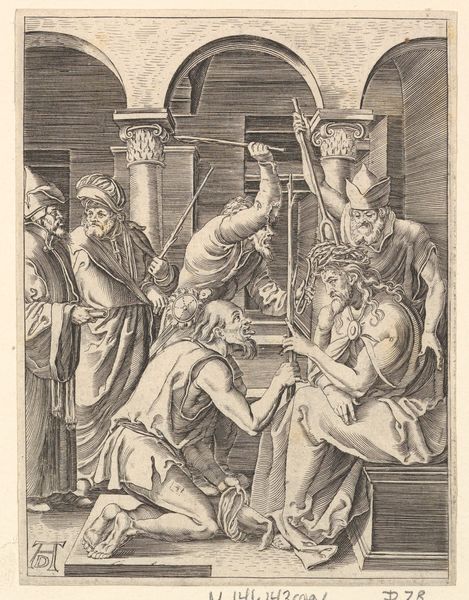

Dimensions: height 153 mm, width 105 mm, height 235 mm, width 181 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. Before us, we have "The Last Supper," a drawing in tempera and coloured pencil, dating back to between 1596 and 1598, created by Zacharias Dolendo. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It’s quite small, isn't it? Intimate almost, for such a grand subject. The coloring gives it a slightly unreal, stage-set quality. What about the details that went into the staging of this iconic moment? Curator: Indeed. Think of the Reformation happening, and Dolendo grappling with religious narrative in a changing Europe. This depiction pulls away from the Catholic iconography prevalent then, placing a humanist lens on the supper, almost like theatre. We can consider how the architecture itself mirrors humanist concepts, reflecting an order accessible through reason. The positioning of the figures, though standard, becomes newly powerful in the face of that upheaval. Editor: And I immediately think about what these colors are comprised of—what are the ingredients here, where did they source the materials, the labor? The application suggests delicate layers; I wonder about the quality of the pencils and tempera available at the time, and how they impacted the final look? And that brown framing within the drawing itself - like architecture—adds another layer of material artifice. Curator: Excellent points. Let’s remember the printmaking culture surrounding artists such as Dolendo. His Last Supper circulated through prints: cheaper access and broad distribution channels allowed reinterpretations. In terms of labor, his works enabled a certain freedom through its reproduction as his commentary would go out to the public, making a political position much more widely understood in public debate than solely as drawings and paintings would have enabled. Editor: The labour of making the colours as well would not have been insignificant, would it? Thinking about ultramarine sourced from lapis lazuli, and its connection to status or luxury makes the whole picture seem newly relevant and materialist, I think. The whole image transforms from purely biblical allegory into social discourse because it speaks to class as much as anything! Curator: Absolutely, it is always a careful balance. By recognizing the conditions and reception of such work, especially by a larger, literate public at this time, we recognize the revolutionary discourse taking form in this historical moment. The material is only part of it but is critical in understanding the entire artwork in terms of reception. Editor: Well, examining art this way opens it up to new possibilities for us, hopefully, to explore further. I appreciate these different readings—each enriches the artwork in unique, yet powerful, ways.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.