photography

#

landscape

#

photography

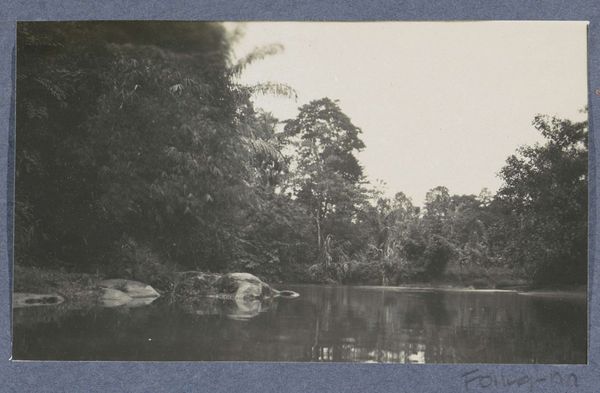

Dimensions: height 80 mm, width 112 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

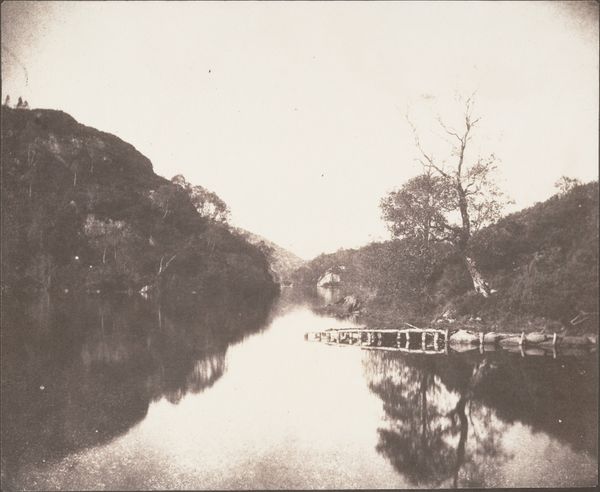

Curator: This is Hendrik Doijer’s photograph, "Gezicht van den Mäabotop op de Saramacca," taken sometime between 1903 and 1910. It captures a vista of the Saramacca River from the Mäabotop. Editor: My initial impression is one of profound stillness. The monochrome palette lends an almost prehistoric quality. The heavy foliage, the water's placid surface... it feels like time stands still here. Curator: Doijer's work is intriguing as it provides visual documentation of the landscape during a period of increasing colonial activity in Suriname. These images served as powerful tools in shaping perceptions of the region both locally and abroad. Consider the inherent power dynamic within this gaze, especially since landscape imagery was historically tied to asserting control over territories. Editor: Structurally, it's a simple but effective composition. The dark, dense foliage frames the river, guiding the eye into the distance. The lack of sharp contrast creates a flattening effect, emphasizing the depth of the scene but blurring any immediate focal point. Semiotically, that tonal uniformity suggests a cohesive unity, or perhaps a certain visual overwhelm to a newcomer faced with such a mass of green. Curator: Right. Beyond the aesthetic interpretation, it is relevant to recognize the position of indigenous populations during this era and how these views might obscure, marginalize, or even erase their presence and lived experiences within the depicted landscape. Early photography played a significant role in shaping social perceptions. Editor: Yes, that tension is palpable. I also notice how Doijer subtly uses the reflection on the water. It acts almost like a muted mirror, doubling the visual weight of the forest canopy. Curator: Photographs such as these provided information and acted as propaganda—influencing policy and impacting indigenous people, maroon communities and even shaping public opinions on colonialism itself. Editor: Looking closely, the texture—the almost granular quality—of the early photographic process becomes quite apparent. That adds an almost haptic dimension; one can almost imagine feeling the humidity. Considering the historical context informs that sensory input powerfully. Curator: Exactly. Studying these images permits insight into that era and the shaping of lasting post-colonial narratives. Editor: For me, the image speaks to the quiet grandeur of the natural world. Curator: And I'm left contemplating its complex role within the history of colonial Suriname.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.