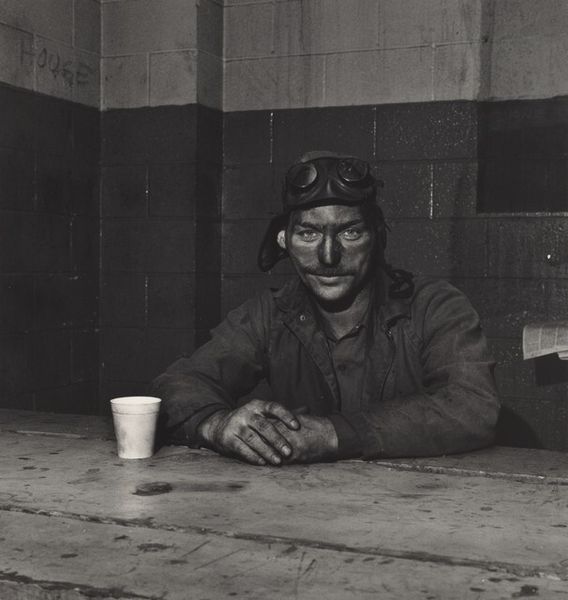

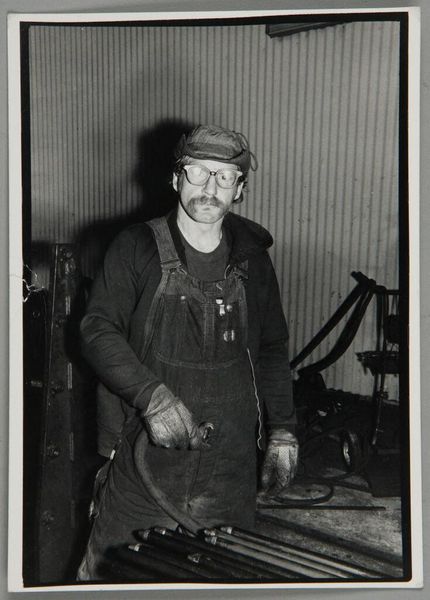

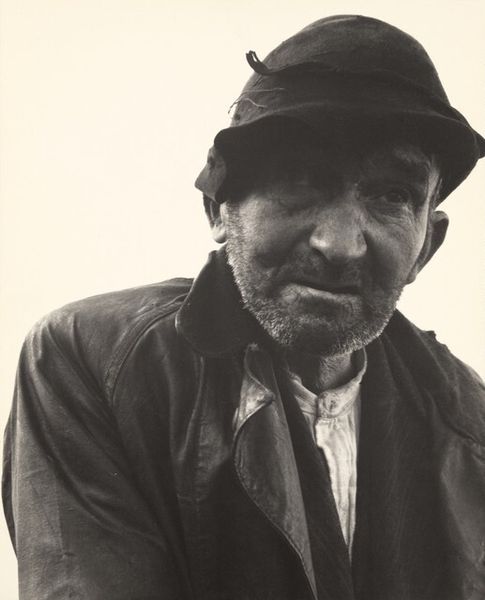

Benjamin Boofer, Shenango Ingot Molds (Working People series) 1977

0:00

0:00

#

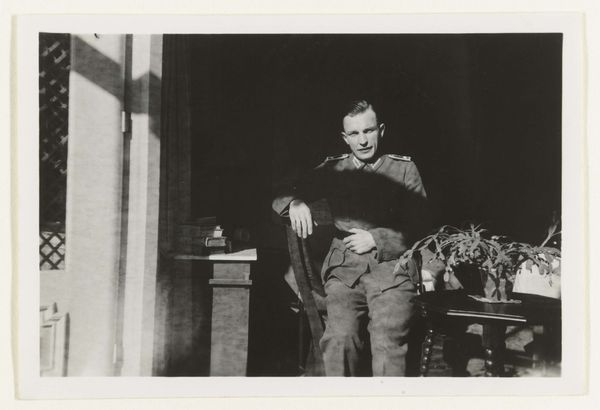

wedding photograph

#

black and white photography

#

photo restoration

#

portrait image

#

black and white format

#

historical photography

#

black and white theme

#

black and white

#

single portrait

#

monochrome photography

Dimensions: image: 18 x 17 cm (7 1/16 x 6 11/16 in.) sheet: 25.3 x 20.3 cm (9 15/16 x 8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

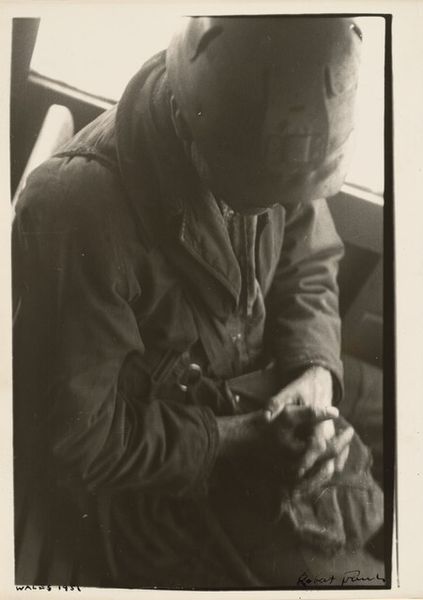

Editor: We're looking at Milton Rogovin's "Benjamin Boofer, Shenango Ingot Molds (Working People series)," taken in 1977. It's a striking black and white photograph of a steel worker. What strikes me most is the quiet dignity in his eyes, despite the obviously hard conditions of his work. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see a powerful commentary on labor and class, situated within the socio-political landscape of late 20th century industrial America. Rogovin, throughout his career, used photography as a tool for social justice, focusing on marginalized communities and working-class individuals. The grime on Benjamin’s face isn't just dirt; it's a visual marker of exploitation. Editor: Exploitation? In what way? Curator: Think about the era. Deindustrialization was looming, and unions were under attack. This image, with its unflinching portrayal of a worker seemingly caught in a moment of respite, implicitly critiques the systems that devalue human labor while simultaneously relying on it. Look at the vulnerability in his gaze. How does that connect to broader issues of power? Editor: I guess seeing him so exposed, without any glamour, makes the wealth disparity pretty obvious. It's like, where is all the money going if not to the people doing the actual work? Curator: Exactly! And Rogovin is making a statement. This image enters into dialogue with conversations around environmental racism, too. Where are these factories located? Who is bearing the brunt of the pollution? It's all interconnected. Editor: I never really thought about photographs in connection to so many different things at once. Curator: It's about seeing art as part of a larger web of social and political forces. And also remembering that photographs, especially portraits, have the power to affirm dignity and resistance. Editor: I’m definitely going to be looking at portraits differently now, thanks. Curator: Me too. The conversation itself can change how we see the artwork.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.