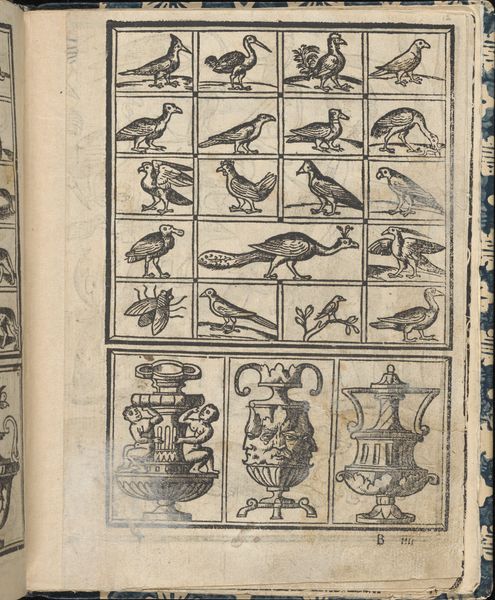

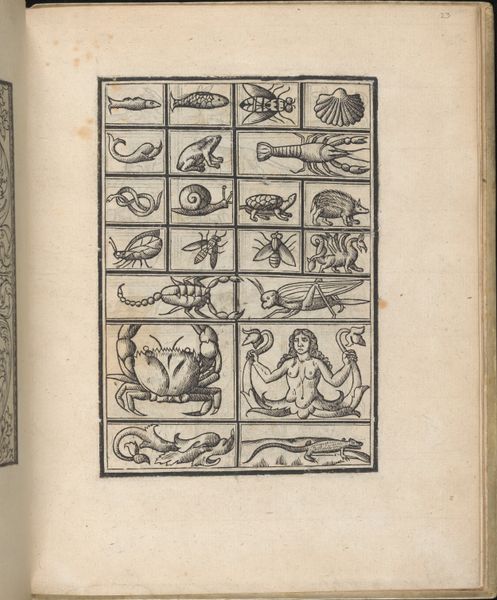

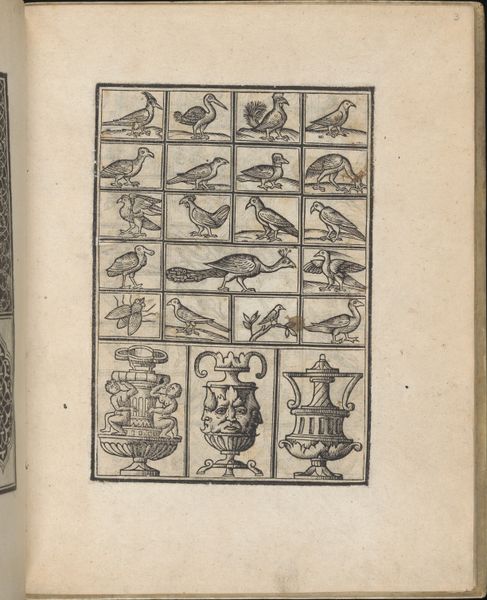

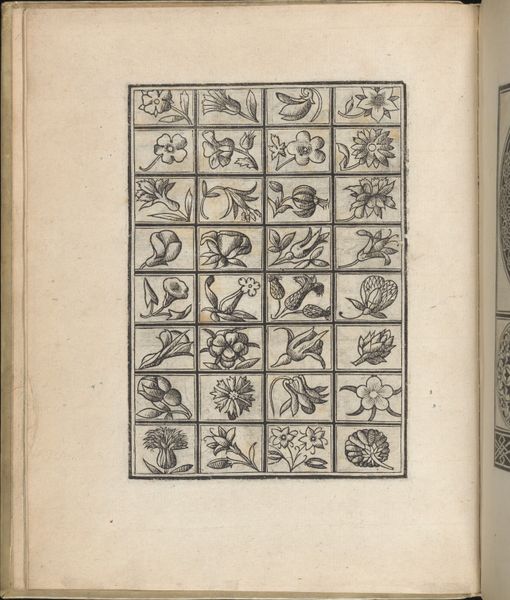

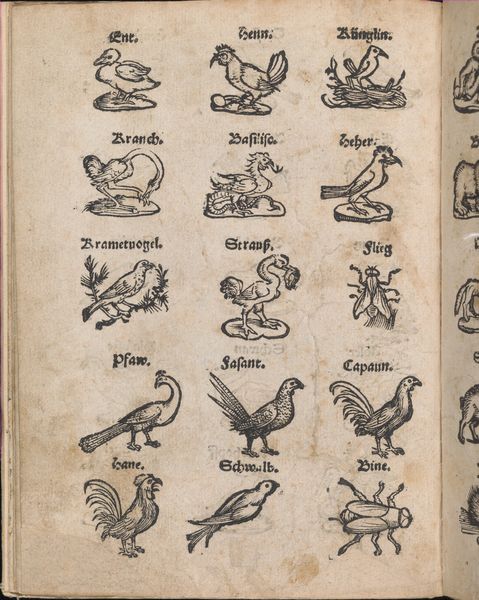

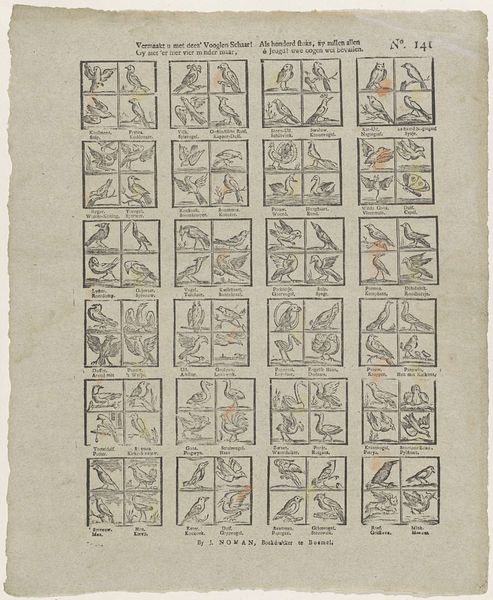

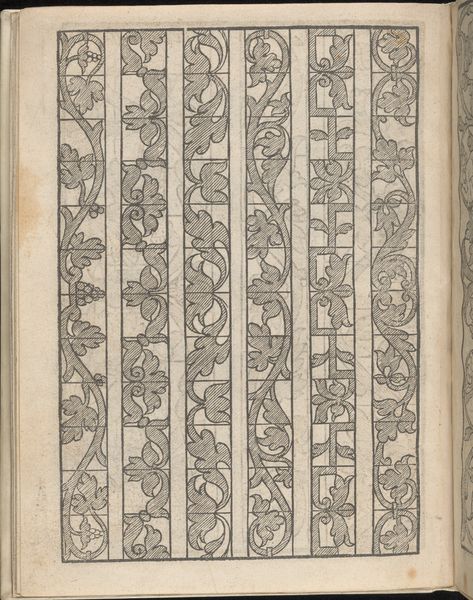

drawing, print, paper, ink, woodcut

#

drawing

# print

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

geometric

#

woodcut

#

italian-renaissance

Dimensions: Overall: 7 13/16 x 6 3/16 x 3/8 in. (19.8 x 15.7 x 1 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

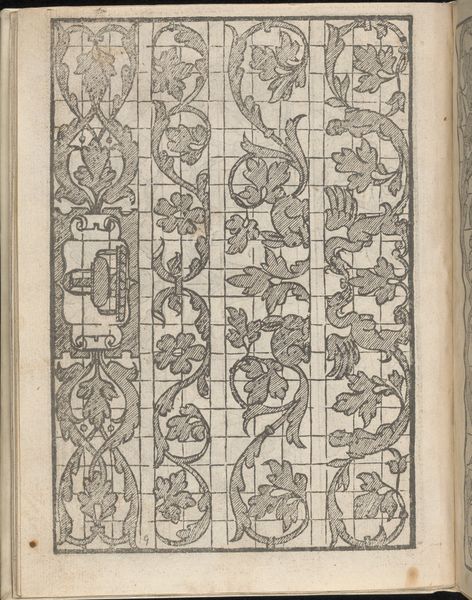

Curator: This is a page, specifically page 10, from "Essempio di recammi" by Giovanni Antonio Tagliente, dating back to 1530. It's an example of a woodcut print showcasing different embroidery patterns. Editor: It feels so orderly, almost like a botanical chart but imbued with a touch of whimsy. Each little floral design is nestled neatly in its square, creating a grid of potential. Curator: Precisely. Tagliente was active in Venice and this pattern book was very influential. Woodcuts like this allowed for the wide dissemination of designs that women could then use to create their own needlework, democratizing access to stylish designs. It represents the early printed book market targeting a female audience. Editor: It’s intriguing to think about who these women were and the communities they occupied. To what extent did such imagery affect constructions of gender and ideals about the domestic sphere? These little grids seem to confine as much as they liberate! Curator: Well, on the one hand, it expanded decorative options. Before this level of printed distribution, women would have had limited exposure to diverse styles of embroidery and limited ability to achieve stylistic variations and updates to design. But, you’re right; the patterns were explicitly marketed towards women within a patriarchal structure, positioning needlework as a virtuous pastime. Editor: So, art shaping life, but within strict boundaries. It also speaks to the increasing commercialization of creativity. An artwork like this makes me think about who benefits when “art” becomes "content." The question arises—how much creative agency do these embroiderers have if they’re simply replicating someone else’s designs? Curator: But also consider that embroidery had significant value in social contexts, representing everything from wealth to domestic harmony, so having fashionable patterns helped with upward mobility. This sort of design could act as a guide for individual makers in creating the means to signal their values in a social setting. Editor: Yes, social currency is vital to consider! It also challenges my view of art as an "individual act". So often in history, creative and artistic labor have been profoundly communal, as perhaps here! Looking closely reminds me how limiting the standard narrative of lone-genius artists truly is. Curator: Absolutely, it prompts us to re-evaluate the purpose of image-making and question who dictates what 'art' truly is, especially when the image is intended for broader social and material application. Editor: Reflecting on this image makes me think about accessibility, labor, the social meanings encoded into visual imagery, and the complicated relationship between art, design, gender, and economics. Curator: And I am thinking of distribution networks and how visual design became integrated with both print and feminine consumer markets. A complex weave!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.