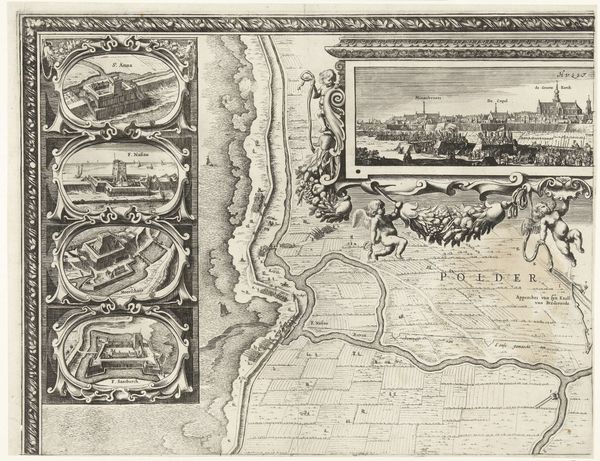

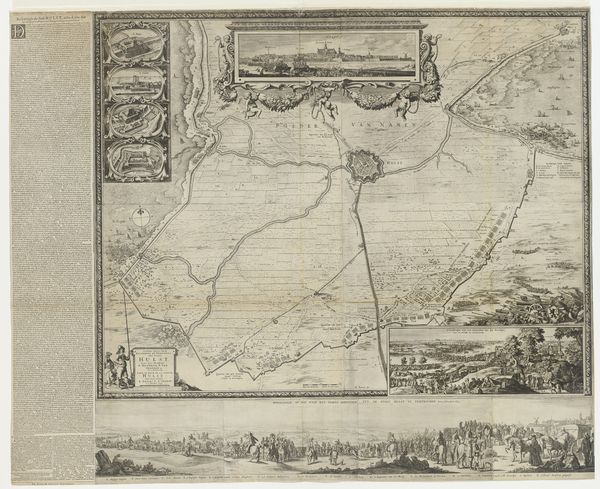

print, etching, engraving

dutch-golden-age

etching

old engraving style

geometric

line

engraving

Dimensions: height 532 mm, width 677 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

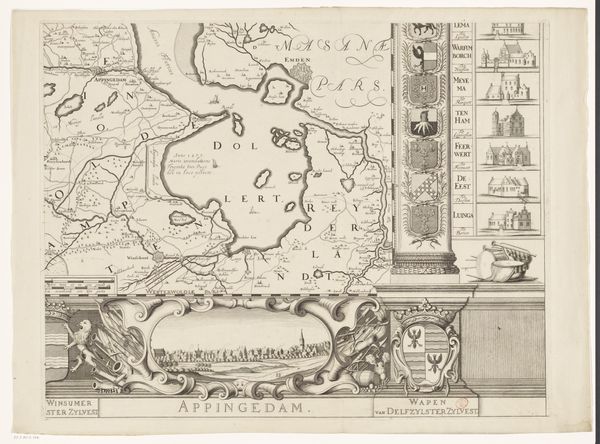

Editor: Here we have "Kaart van de provincie Groningen (deel rechtsboven)", which translates to "Map of the province of Groningen (right part)". It's an etching and engraving by Cornelis Apeus from 1678. I'm immediately struck by how much more than just a geographical document this seems to be, there’s so much detail and symbolic ornamentation. What's your take on this piece? Curator: It’s a fascinating object, isn't it? Look closely at how Apeus has embedded this geographical data within a carefully constructed visual argument. This wasn’t just about accurately portraying the land; it was about power, ownership, and civic identity in the Dutch Golden Age. Maps were powerful tools used to make claims. Editor: Claims, how so? Curator: Well, consider the decorative elements like the coats of arms. Who are they celebrating and what does that placement communicate? These images aren't neutral; they actively construct a narrative of authority. Maps were also a form of civic pride. Who paid for the maps? Who had access to the maps and who was the audience of those prints? How might the design of the print itself shape the perception and understanding of Groningen for people within the region, and those beyond? Editor: I see. So it’s less about objective representation and more about... political representation. Does this kind of map influence anything at the time? Curator: Absolutely! Maps directly influence political relations, trade routes, and military strategy. Understanding the world, visually, grants control, both perceived and real. The aesthetic choices—the lettering style, the embellishments—are integral to conveying a specific image of Groningen, not just depicting its physical form. Editor: That shifts my whole view of it. I initially saw it as a beautiful, almost quaint historical artifact, but now it feels like a potent political statement cleverly disguised as a map. Curator: Precisely. It reminds us that even seemingly straightforward depictions of the world are laden with social, political, and institutional narratives. And Apeus, as a cartographer, was deeply enmeshed in those narratives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.