#

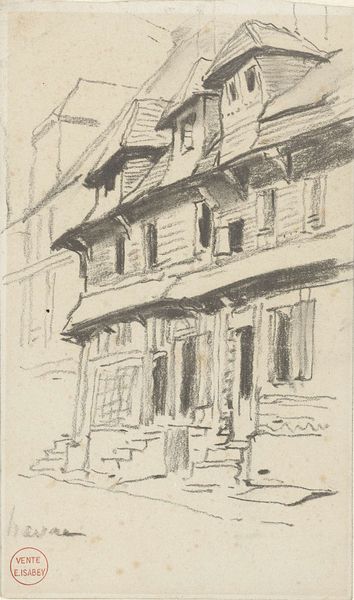

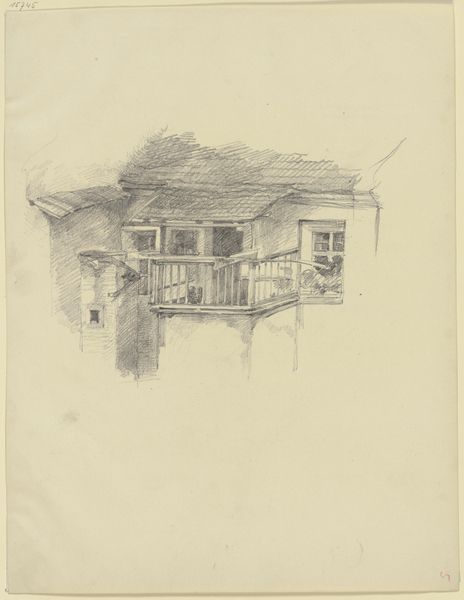

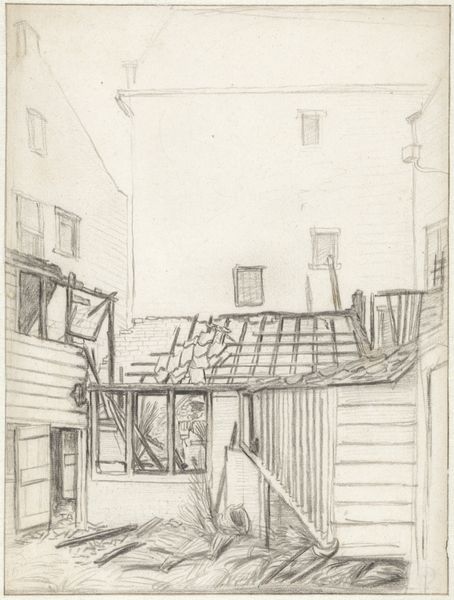

aged paper

#

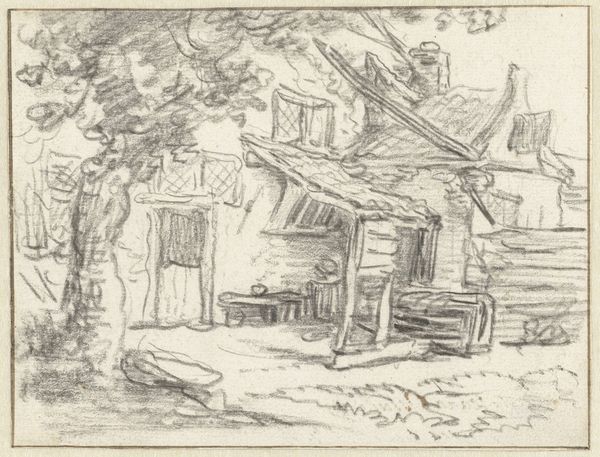

light pencil work

#

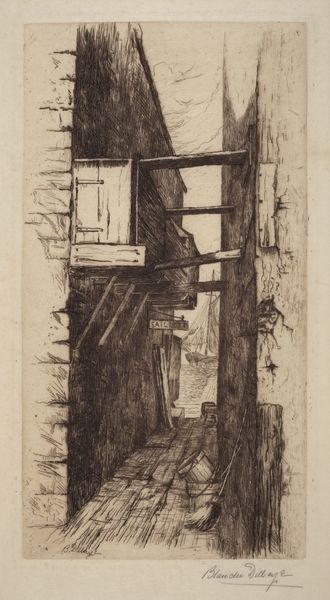

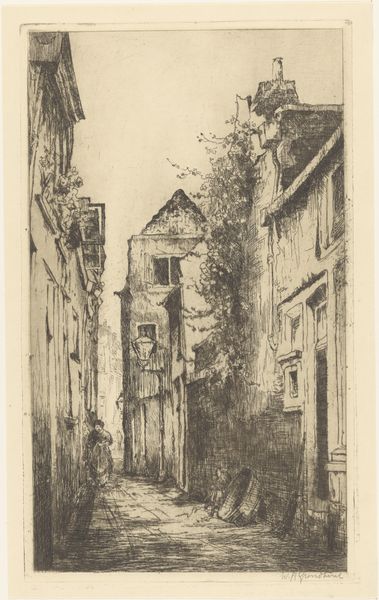

quirky sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

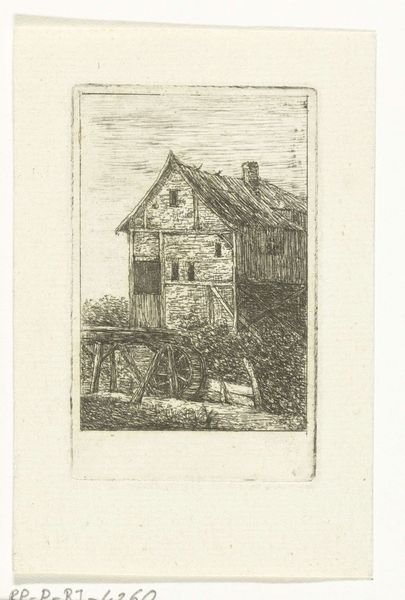

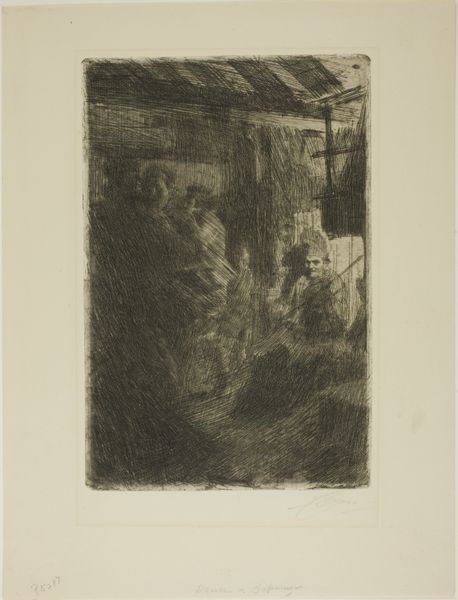

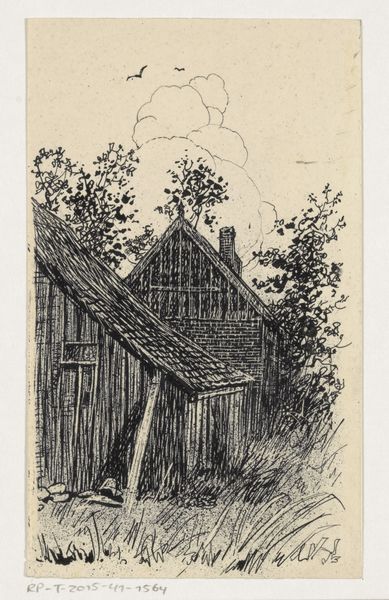

old engraving style

#

sketch book

#

personal sketchbook

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

#

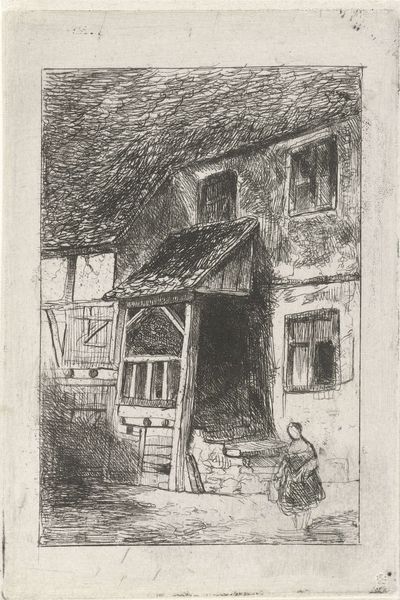

building

Dimensions: height 103 mm, width 68 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Jan Diederikus Kruseman's "Facade of a house with a covered entrance", created sometime between 1838 and 1918. It seems to be a pen and ink sketch, reminiscent of an old engraving. There's a certain quaintness to the scene. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see more than just quaintness. I see a snapshot of the living conditions of a particular class, and perhaps even a subtle critique. Look at the structure: a modest dwelling, likely rural. What does this say about access to resources, to power? Consider who occupied this space and their relationship to the broader socio-economic landscape. Were they landowners, tenants, or perhaps even laborers? Editor: That's a different way to approach it. I was mostly thinking about the artist’s technique. Curator: The technique is important, of course, but let's not divorce it from its historical moment. An artist's choice to depict such a scene is inherently political. Who is being represented, and for what purpose? Think about the power dynamics involved in representation. Whose stories are told, and whose are silenced? The covered entrance, for instance—is it an invitation or a barrier? What about the presence or absence of people? These are not neutral choices. Editor: I never thought about it that deeply. So, by analyzing even seemingly simple architectural sketches, we can unpack larger social and political narratives? Curator: Absolutely. Art is never created in a vacuum. This sketch becomes a document, a piece of evidence that invites us to interrogate the past and present, especially the distribution of power and visibility. It can even lead us to contemplate present-day housing injustices and the ongoing struggle for equitable representation. Editor: Wow, I'll definitely look at art with fresh eyes from now on. I appreciate this perspective. Curator: And I hope this dialogue has highlighted how a seemingly simple sketch can offer complex narratives of historical and social contexts, if only we learn how to read them.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.