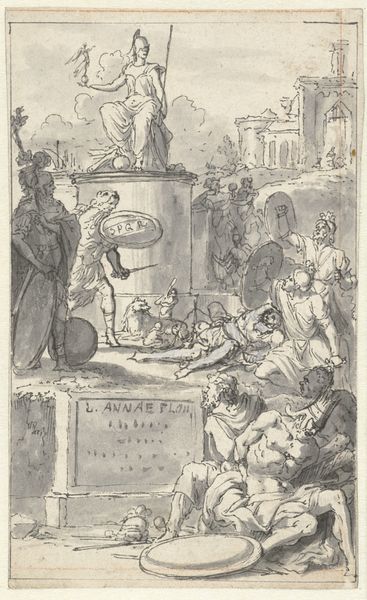

The Arts and Sciences Honoring Their Protector Charles-Theodore, Count Palatine 1777

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: sheet: 18 3/16 x 10 1/2 in. (46.2 x 26.6 cm) plate: 18 1/16 x 10 3/16 in. (45.8 x 25.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Joseph Fratrel created "The Arts and Sciences Honoring Their Protector Charles-Theodore, Count Palatine" in 1777. It's an engraving, currently housed here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: My first impression is just...wow. There's so much going on here! The swirling drapery and cherubs up top are juxtaposed against the stoic, almost severe, figures below. It feels like a celebration struggling against something heavy and formal. Curator: Absolutely. The print operates on many levels. Primarily, it's a piece of Baroque academic art, so think about its context: Charles-Theodore was a patron of the arts and sciences. We see them literally paying homage to him, presenting his portrait. But more broadly, the piece engages with Enlightenment ideals, positioning Charles-Theodore as an enlightened ruler. Editor: You know, seeing that portrait makes me wonder about the relationship between patronage and artistic freedom. Was Fratrel compelled to paint a flattering image, or did he genuinely admire the Count Palatine? It feels like there’s a power dynamic baked right into the artwork itself. I bet it's complicated, no? Curator: Power dynamics are precisely the point. Academic art, by its very nature, is about demonstrating not just technical skill, but also ideological allegiance. And if you consider Fratrel was part of a broader artistic community deeply dependent on patronage, that colours his vision. It is all very interwoven. The arts being offered at the altar of Power! Editor: So the somewhat theatrical grandeur of it all is perhaps part homage, part carefully crafted propaganda? The composition itself seems strategic—almost a play within a print, with all these characters looking towards the same "stage." Are we the audience? Or Charles-Theodore? It’s all very meta when you start thinking about it. Curator: Yes, and if we dig a bit more in the allegorical components—the figure of Minerva and her connection to the Count’s virtues for example—the piece operates also within very conventional and specific historical codes. The historical context offers, undoubtedly, an intersection between propaganda and artistry that are central to any serious discussion about this piece. Editor: Thanks to all of that, what could have been merely a portrait transforms into something more meaningful and critical to consider, isn’t it? I will leave looking differently now. Curator: It always works, indeed. It is the meeting of perspectives, what matters at the end of it all!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.