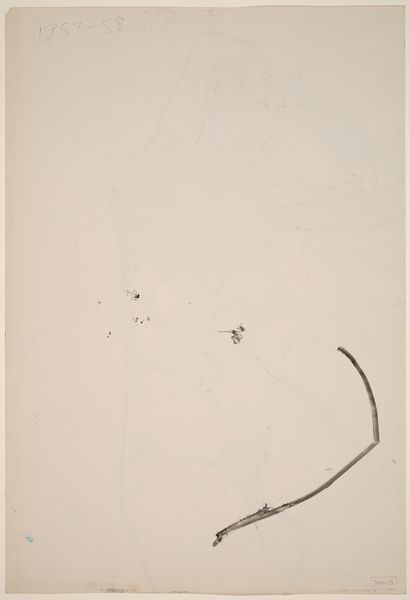

drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

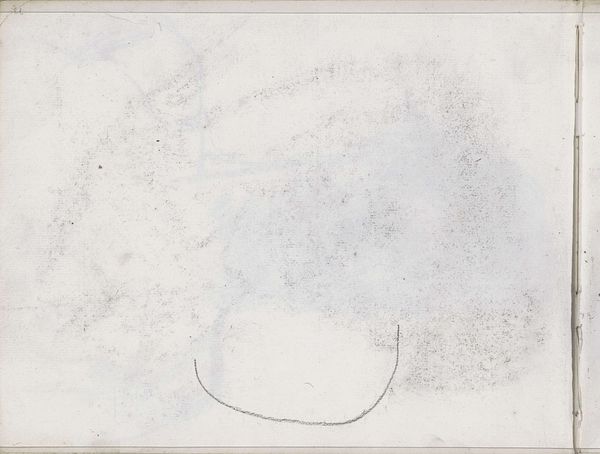

paper

#

ink

#

line

#

sketchbook drawing

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here at the Rijksmuseum, we have a work from Isaac Israels, dating from between 1875 and 1934. It's entitled "Abklatsch van de pentekening op pagina 12." Editor: That translates to something like "copy of the pen drawing on page 12," right? It’s mostly ephemeral. Like looking at a ghost image. Very minimal. The ink strokes are confident, but the faded impression of a sketch underneath gives it an interesting sense of layers. Curator: It's a fascinating glimpse into Israels' process, almost like we're looking at an unedited thought. There's a visible wiping away or palimpsest of another drawing that's nearly gone, only traces remain. Editor: It's more like visual archaeology. A record of what Israels considered important enough to preserve or copy. Were sketchbooks common practice at the time? Were they only affordable for people like him from wealthy families? What images are elided with erasure? These are questions I’m thinking of when seeing work like this. Curator: Precisely. The act of sketching was essential, ingrained within artistic training during that era, solidifying observational and representational skill. His societal standing provided not only leisure, but social avenues into certain milieus where sketching would take place: for example, portraiture and depictions of the every day were becoming more viable subject matter. Editor: And perhaps an understanding of erasure, not only as practical when the work is bad or unsuccessful, but in this case almost an embrace of its incomplete quality? I find something compelling in its unfinished air. The negative space is alive. Curator: That ambiguity grants a peculiar dynamism. There's a raw authenticity here that speaks beyond mere draftsmanship; an emotional honesty surfaces in the immediate transfer from thought to form. It is, after all, both finished copy and first draft simultaneously. Editor: It leaves one wondering, what was the original intention, and how do accidents like the smudge in the left, affect interpretation, and what kind of statement about labor is being made here by this sketch of a sketch? Curator: These visual residues hold tremendous insight for those interested in examining these socio-cultural nuances, and the museum functions as a place where we are able to interrogate those elements for visitors and communities who pass through our doors. Editor: Definitely an image that invites questioning rather than provides easy answers. That's what sticks with me.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.