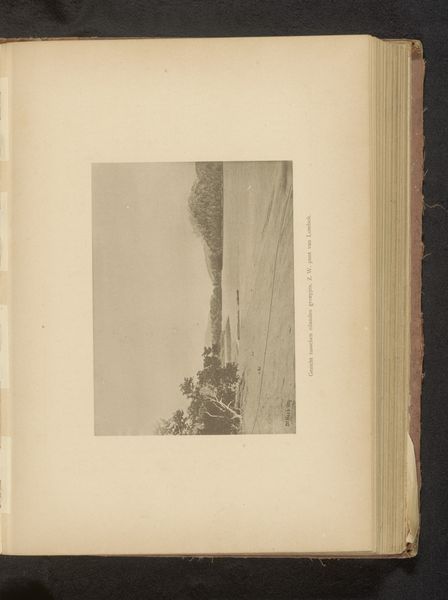

print, photography

# print

#

book

#

landscape

#

photography

#

academic-art

Dimensions: height 118 mm, width 167 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this spread, what strikes you first about this photographic print, entitled "Gezicht op Calvi?" We know it was created before 1890, and it’s attributed to Roland Bonaparte. Editor: Its starkness. The black and white emphasizes a real sort of bleakness to this seaside settlement, especially given it's presented within what appears to be a bound book. It raises questions about who would possess such an image and for what purpose. Curator: Bonaparte was actually quite the accomplished geographer and cartographer! Given his social standing and scientific curiosity, what inferences might we draw from the decision to capture Calvi from this particular perspective? Editor: Well, there's a certain flatness to the scene despite the natural landscape. My thoughts turn toward colonialism. What labor supported such expeditions, who profited from documenting distant lands in print, and for whom was it consumed? Was it scientific record or imperial propaganda? Curator: Indeed. The framing suggests control and observation from a distance, an act of possessing space through documentation. Think about photography’s capacity in that era for constructing narratives about identity and land. Editor: The photogravure printing process adds to this. There’s a sense of mass production implied, a spreading of this perspective widely beyond a singular experience. Curator: Consider also how this fits into the larger history of landscape art. Artists and photographers frequently choose subjects based not solely on beauty but because of social and historical narratives associated with place. Editor: Absolutely. The labor, the production process itself becomes part of the content; it can reinforce existing hierarchies while appearing purely documentary. Curator: Examining its place in a book gives us insight into who had access to such images and their broader cultural influence. What the intention of capturing a place that may hold different connotations, political weight and meaning across social and economic divides. Editor: It transforms from just an image to a constructed perspective, reflecting the power structures of that moment in history. Understanding this makes us more critical viewers of even seemingly neutral documents.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.