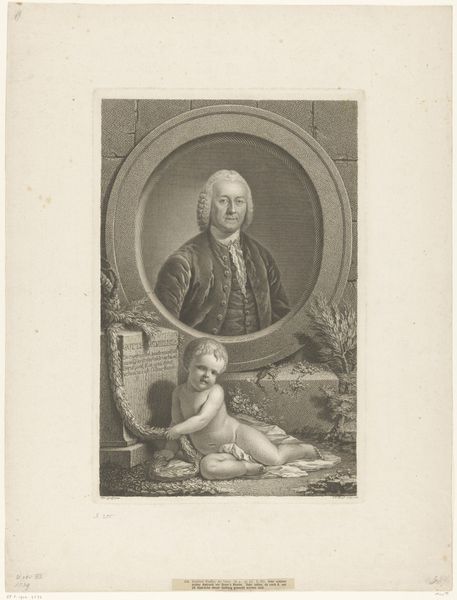

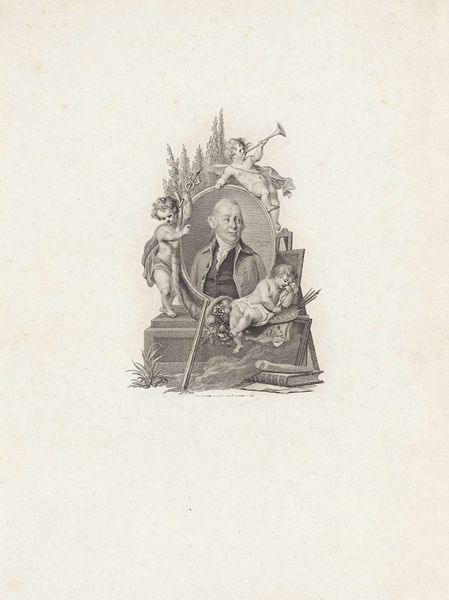

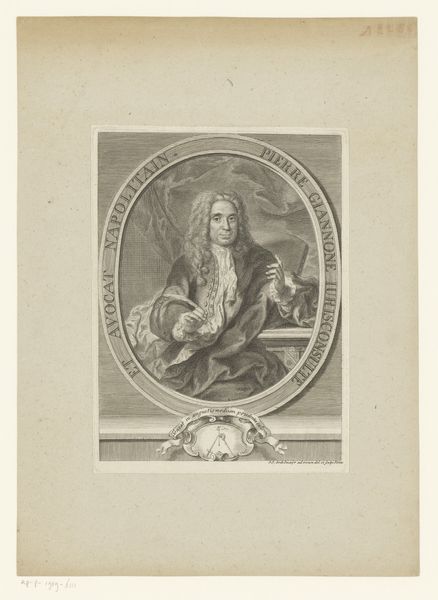

Dimensions: height 187 mm, width 145 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, here we have the "Portret van Johann Carl Wilhelm Moehsen" created sometime between 1771 and 1775 by Georg Friedrich Schmidt. It's an engraving. The cherubs at the bottom are kind of distracting. What strikes you most about this piece? Curator: Well, look closer. Notice the materials depicted. Beyond just a portrait, what's actually being portrayed? See those scattered books, the inkwell, and writing implements at the base. It suggests scholarship and intellectual pursuits, even down to the labor. Consider what an engraved portrait, like this print, *is*. It's not some fleeting painting done for wealthy patrons, it's explicitly reproductive. Editor: Reproductive? Curator: It's inherently linked to dissemination. Schmidt’s work speaks to the rise of a literate public consuming images and texts. Think about the economic implications. The printing press, engraving techniques…these are the material means that made the Enlightenment possible. It allowed knowledge, including images of important people, to spread wider and faster. Editor: That makes sense. I hadn't thought about the print itself as part of the meaning, but it *is* the whole medium! Curator: Precisely! And the inclusion of those playful cherubs points to a celebration of knowledge itself as a playful, almost unruly, pursuit, produced through someone’s literal hand. But who exactly had access to all of this? And to what end was all this accessible knowledge actually serving? Editor: That gives me a lot to think about regarding accessibility and consumption, both of which influence how we see the artwork today. Thanks! Curator: My pleasure! Always good to remember art doesn’t exist in a vacuum; it's intertwined with its method of production, materials, labor, and historical context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.