#

oil painting

#

portrait reference

#

acrylic on canvas

#

animal portrait

#

animal drawing portrait

#

portrait drawing

#

facial portrait

#

portrait art

#

fine art portrait

#

digital portrait

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

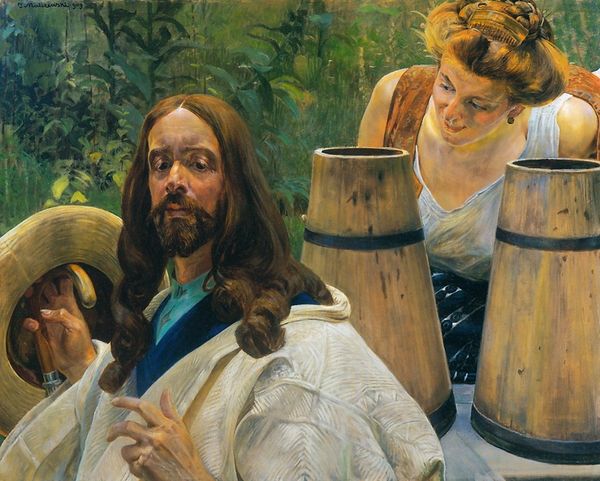

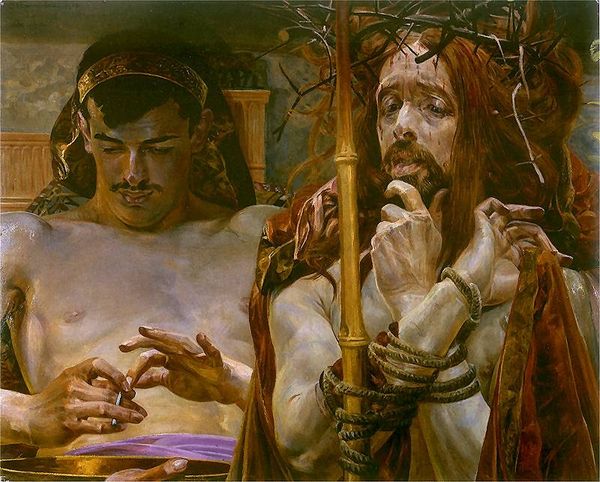

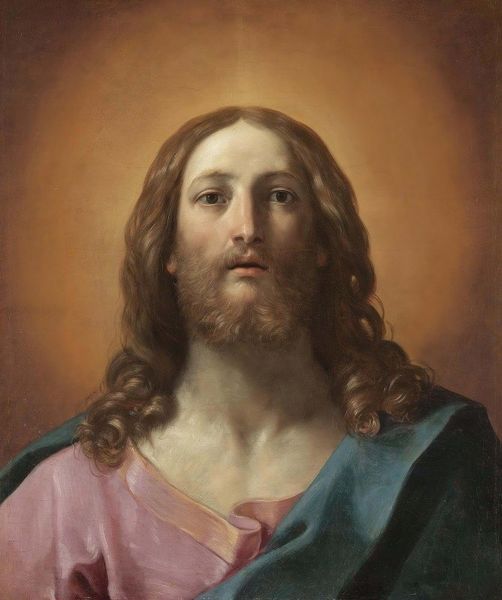

Curator: Let’s take a look at Jacek Malczewski's, "Christ in Emmaus" created in 1909; this piece being the central section of a triptych. Editor: It's unexpectedly domestic. There's a stillness to the scene, an everyday quality juxtaposed with the monumental figure. I immediately see that and I'm interested in its materiality – the subtle folds in the robes and luminosity of that drink. Curator: The historical context here is crucial. Malczewski, a leading figure in Polish Symbolism, was deeply engaged with the socio-political struggles of Poland under foreign occupation. This reimagining of Christ, as a very Polish looking individual, offered a subversive, if subtle, symbol of hope for national resurrection during a time of intense political suppression and cultural identity being suppressed. Editor: That's a really great context, thank you. Considering the means of production though, it appears to be executed using fairly standard oil on canvas. I'm intrigued by the way light seems almost woven into the fabric of his garments. Almost like humble homespun made divine. Curator: Yes, that's a really beautiful observation. Malczewski often used religious subjects to explore themes of Polish identity and national suffering. He’s portraying Christ not as a divine king but almost as an intellectual revolutionary, a powerful commentary on Poland’s political position and yearning for self-determination through their connection to religion. The original painting of which this is only a small piece, speaks to the deep yearning that occupied Poland’s intelligentsia and creatives. Editor: I see that deep tie in religion now, and understand how revolutionary that may have been. Knowing that it’s oil and not some more elaborate media reinforces that. And seeing as oil paint became a mainstream media that was readily available and easier to acquire, use, and therefore reproduce, democratizing artwork is what that does in effect. This connects deeply with your previous mention of social commentary. To that, I'll add: despite its religious iconography, there's an undeniable feeling of intimacy, even domesticity that counters the expectations and really grounds it, making the work profoundly relatable. Curator: That relationship that normalizes this scene humanizes it, and in doing so provides the piece a means for commentary that doesn’t overshadow the message. Editor: It's a really subtle blend of divinity and everyday life, a conversation with labor through common media of the era, that feels uniquely powerful in its message of shared history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.