drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 47 mm, width 81 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

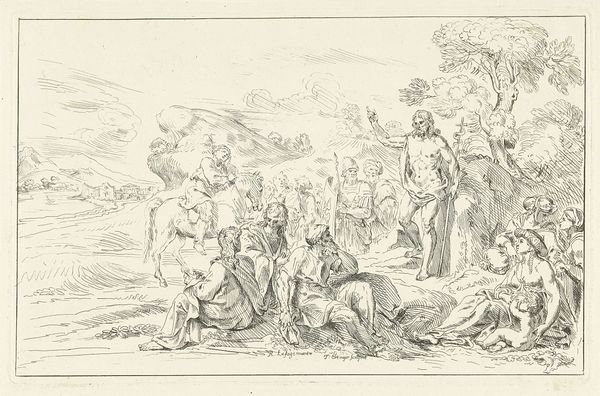

Curator: Here we have Augustin de Saint-Aubin's "Moses with the Tablets of the Law," a print dating to 1759, housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first impression is of etched delicacy; the light is ethereal, but there's something stiff, almost rote about the figures. You can sense the engraver's careful labour in those fine lines. Curator: Saint-Aubin, of course, worked in a world where prints disseminated ideas. This piece shows a key moment in the story of Moses, a crucial element for Protestant theology and moral codes throughout the 18th Century. Editor: Absolutely, the tablets themselves, rendered so meticulously, take center stage. But think of the conditions: the etching process, the copperplate, the inks used. The availability of these materials surely impacted the accessibility of the image. It’s also worth examining where it was made – probably in a studio – how workshops may have collaborated in producing images for wider distribution. Curator: That's a great point; the production is essential to understanding its reach. And the visual rhetoric itself – the emphasis on Moses as lawgiver served the sociopolitical role of providing models and frameworks, religious or otherwise. Editor: The way they are revering Moses and, therefore, those tables. The bodies react! Are those contorted poses reverence or dissent? They feel slightly manufactured, posed. Curator: The Baroque certainly enjoyed drama. And indeed, the ambiguity serves the purpose. One must contemplate whether one accepts this Law! I’m interested in what Saint-Aubin may have understood to be his own contribution to these narratives through his compositions. Was he aware of his role in shaping collective consciousness around figures such as Moses? Editor: What were the labor conditions to allow for pieces such as this? How do those working at various steps relate to or conceive this image as embodying divinity? What are the power relations intrinsic to this image's means of dissemination? That really alters the discussion for me. Curator: These details give us such insight! Thinking of the broader reception and how the engravings circulated – for education, devotion, even decoration. The image is therefore so vital for cultural dialogue, but to fully see it requires both material investigation and social reflection. Editor: Indeed, to grapple with what informs both its production and the world in which it functions and has consequences.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.