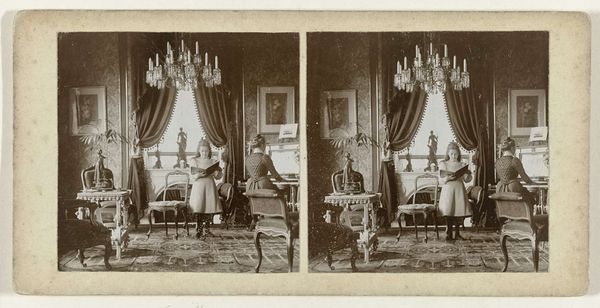

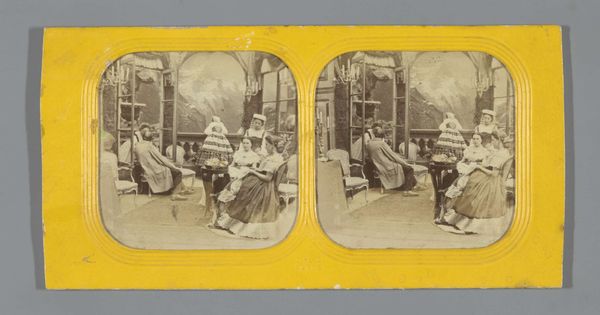

Portret van Henry Pauw van Wieldrecht (links), Adriana Johanna ('Jenny') Pauw van Wieldrecht (rechts) en hun moeder, Aletta Cornelia Anna Voombergh c. 1869 - 1873

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 71 mm, width 162 mm, height 84 mm, width 170 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: The sepia tones give it an aged feel, like looking through a misty window into the past. It depicts a mother with her son and daughter seated around a table laden with objects, isn't it? Editor: Precisely. This intriguing work is titled "Portret van Henry Pauw van Wieldrecht (links), Adriana Johanna ('Jenny') Pauw van Wieldrecht (rechts) en hun moeder, Aletta Cornelia Anna Voombergh". Likely produced as a gelatin silver print sometime between 1869 and 1873, it exists as a testament to a specific moment within that family's history. The image strikes me, though, with a certain formality. It is so stiffly posed; they seem quite self-aware of being observed and memorialized. Curator: And consider that this photograph comes from a period of relative transition. Although these domestic images seem timeless and eternal now, consider the implications this medium had for family and gender in late 19th-century Holland. How fascinating that such an intimate genre scene could have far reaching cultural implications at the time! Editor: True, the context shapes our perception. But I can't help noticing those little details. The cactus for example sitting in the table center. Symbolism often resided in the seemingly mundane, imbuing the photograph with layers of unspoken meaning. Curator: Cacti carry associations of endurance, perseverance... things rooted in the desert and hardship... But do they suggest familial perseverance here? Editor: Well, that is the core question, isn't it? Beyond just documentation of a moment, photography gains prominence within genre painting. What are these portraits trying to express or elicit? I see, instead, the cacti acting as an aesthetic object. An eccentric accessory demonstrating refinement and elevated taste. Curator: That feels reductive, doesn't it? This image provides an entryway into the emotional terrain of familial connection. To simply ignore all symbolic weight—! Editor: Well, either way, there is some visible damage to this silver gelatin print that only enhances its inherent melancholic qualities. Curator: Ultimately, isn't art always speaking in riddles? These glimpses into history—through the eye of a lens or even a familial cactus—leave you endlessly thinking. Editor: Yes, thinking and hopefully seeing how portraits acted as socio-cultural and art objects. Each family image can reflect wider political and class assumptions in such early uses of the medium. Thank you for your iconographical approach; I would not have examined that familial lens as carefully without your insights.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.