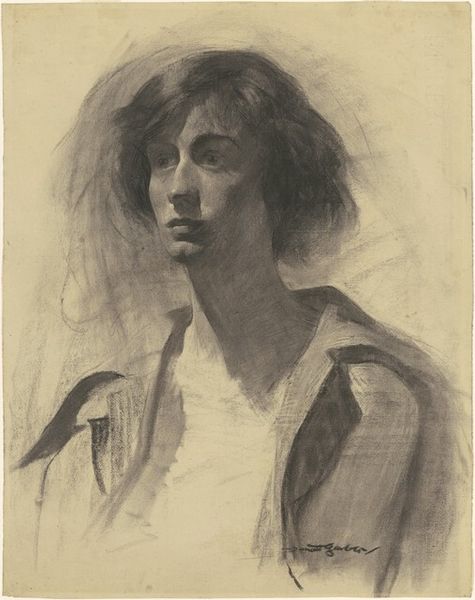

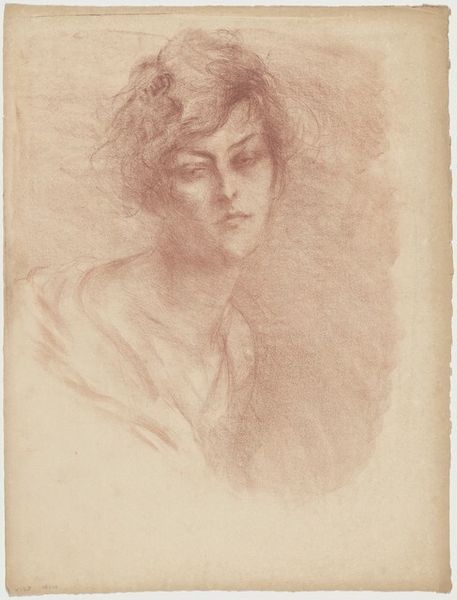

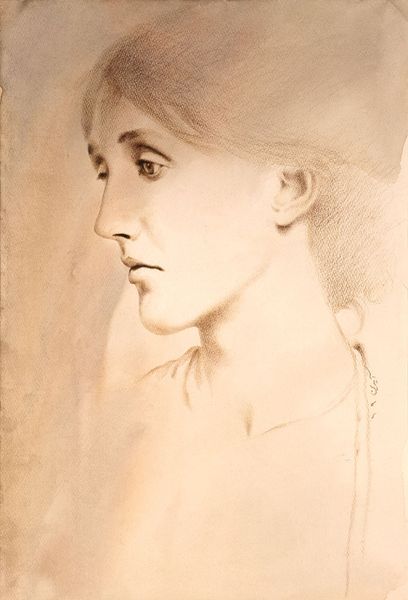

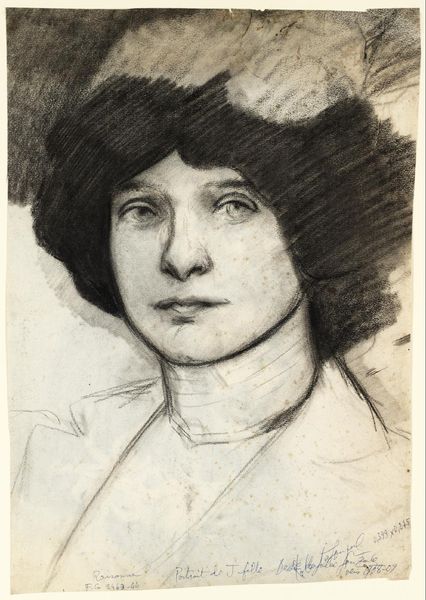

drawing, pencil, charcoal

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

head

#

face

#

pencil sketch

#

charcoal drawing

#

pencil drawing

#

sketch

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

charcoal

Dimensions: 41.9 x 24.7 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: Adolf Hiremy-Hirschl's "Portrait of the Artist's Daughter Maud" is rendered with a delicate combination of pencil and charcoal. Editor: It strikes me immediately as quite soft. There’s a haziness to it, like a memory half-faded. You can almost feel the yielding quality of the charcoal. Curator: The soft rendering lends an ethereal quality, doesn't it? Think about the socio-political constraints on women's roles, especially daughters, within patriarchal family structures during Hiremy-Hirschl's time. This piece can be interpreted as speaking to those constraints through its gentle representation of Maud, perhaps even as an attempt at imbuing her with a certain agency through art. Editor: Right, and that ethereality probably owes quite a bit to the techniques he used. You can see where the charcoal is smudged to create gradients and blur boundaries. That blending is skillful—look at how he builds up tone around the head, and leaves other areas like her shoulders only lightly sketched. Was this intended as a preparatory study, do you think? It feels… unfinished, somehow, yet intentional. Curator: It's likely a study, yes, though the nuances are ripe for deeper exploration. Maud’s gaze, directed off to the side, invites us to question her thoughts, her position as both muse and daughter, and the male gaze that governs portraiture as a genre. There is tension created between objectification and endearment in a patriarchal familial setting. Editor: And I am thinking that the material choices, the swiftness allowed by charcoal, even the apparent incompleteness, may have been vital in capturing something fleeting and genuine. It is so different from more laboured academic portraits that might prioritize a display of skill over conveying this feeling. It reminds you how different art was considered when these material and faster processes were more obviously a process, rather than a final end. Curator: I appreciate you grounding this in the physical and temporal aspect of creation. The seeming incompleteness in conjunction with charcoal smudging speaks to our own imperfect and mediated understandings of historical portraiture. Editor: For me, the focus on the immediate, the tangible act of making the artwork, reveals far more about its value than perhaps the image depicts, reminding us to think about process in order to know production. Curator: Exactly! Thinking through art in relation to social power illuminates why these processes, even seeming incompleteness, should be seen as important elements of consideration when discussing the portrayal of women within portraiture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.