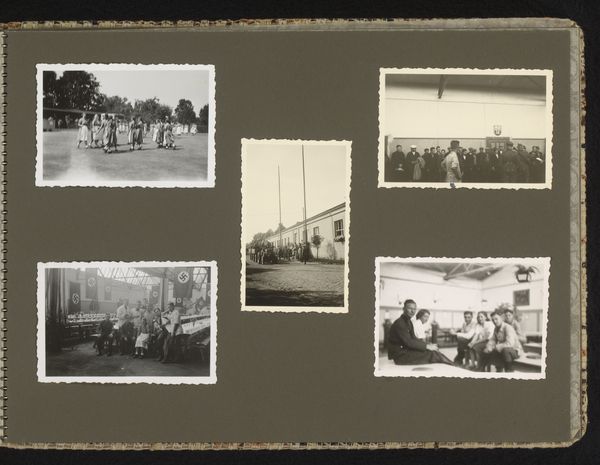

photography

#

portrait

#

photography

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 90 mm, width 61 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: The photograph we’re looking at is entitled “Corry Mak van Waay-Zulver met Joyce in een kinderwagen,” which translates to “Corry Mak van Waay-Zulver with Joyce in a stroller.” It’s a 1932 work. It seems to hover in the space between realism and genre painting through the lens of a portrait. Editor: There’s a wonderful sense of quiet domesticity. A young mother with her child. But the sharp contrast of the black-and-white medium adds an edge. Curator: It's interesting that you see domesticity, I am more captured by the gaze, which could mean several things. Let's contextualize it a little. Think of the societal pressures and expectations placed on women during the interwar period in the Netherlands. Corry, elegantly dressed, is caught between the modern world, as women became more emancipated, and motherhood. That sharp contrast underscores that tension, doesn't it? Editor: Precisely, and to your point, it makes you think about how materials help make these tensions more prominent. In the stark tones and composition of this photograph, which emphasizes this in-between status, we see labor materialized in choices like clothing and the production of family. There is something about a photograph on photo paper that communicates that historical period. Curator: Absolutely. Consider too, how genre painting often depicted idealized versions of everyday life. Here, we have realism tinged with personal narrative—it isn't necessarily supposed to portray something so elevated, in my opinion. How does the child, Joyce, feature? As another potential pressure or maybe a beacon for the woman, which leads me to assume a positive undertone as opposed to you maybe, a sense of tension. Editor: I think the picture encapsulates this quiet moment in a much broader discussion. From the point of view of Joyce who stares front, while the mother remains looking in one direction, she knows what to do. It could even mean that this mother wanted something similar for her. That duality in material, mother versus daughter, and expectation, adds layers of social discourse on what could easily be a sweet picture of mother and daughter. Curator: Ultimately, it reveals how something seemingly straightforward, like a mother and child portrait, actually holds multitudes when we examine its historical context and cultural meanings. Editor: And that examining materiality offers tangible access into that history. Thanks for opening up my perspective.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.