#

pop art-esque

#

pop art

#

neo expressionist

#

acrylic on canvas

#

pop art-influence

#

men

#

facial portrait

#

chaotic composition

#

portrait art

#

fine art portrait

#

digital portrait

Copyright: Public domain US

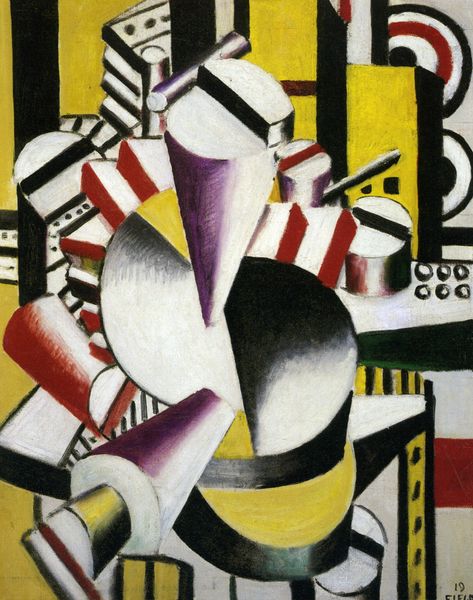

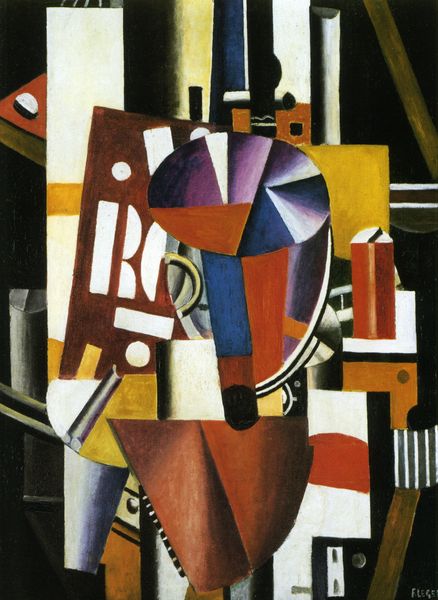

Editor: Right in front of us, we have Fernand Léger’s “Still life in the machine elements,” from 1918. It is strikingly…mechanical. I see these cones and cylinders and I wonder how it relates to other still lifes. How do you interpret this work? Curator: Well, let's think about the materials. It's paint on canvas, sure, but look at what he's depicting. It isn't fruit or flowers; it’s elements of a machine. We need to consider this in its social context, in 1918, at the end of World War I, after a century of increasing industrialization. Editor: So the objects aren't "natural", they're made? Does that shift the purpose of a still life? Curator: Precisely! This is a still life of production, of the building blocks of industry. Look at the clean lines and simplified forms, how they reject organic shapes. Léger is showing us a world increasingly shaped by human labor and manufacture. He highlights materials and processes. Ask yourself, where do we find this celebration of materiality in everyday life? Editor: I guess in factories? Or, like, in product design today, maybe? It almost makes the *making* of things the point, not the thing itself. Curator: Exactly! It forces us to think about our relationship with industrial production and how it impacts our lives, aesthetically and economically. What do you take away now from that close looking? Editor: It feels like Léger isn’t just painting an image; he’s commenting on the means of *making* that image and all of our surroundings. The process itself becomes the message. Curator: Yes! Seeing art as a reflection of, and a participant in, the systems of production around it, gives us fresh appreciation for it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.