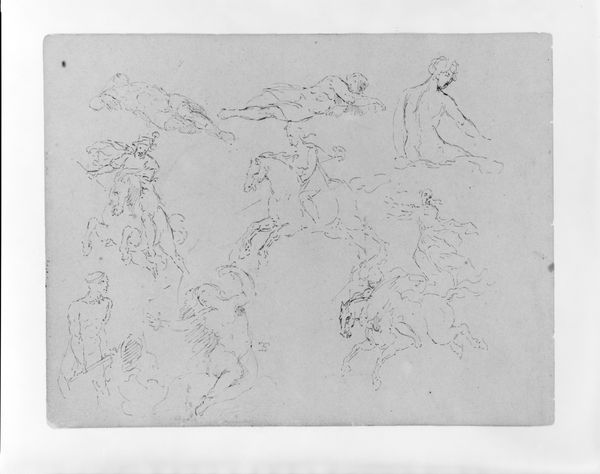

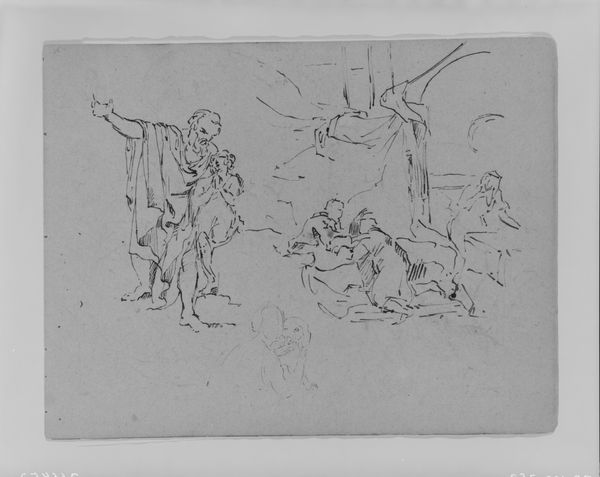

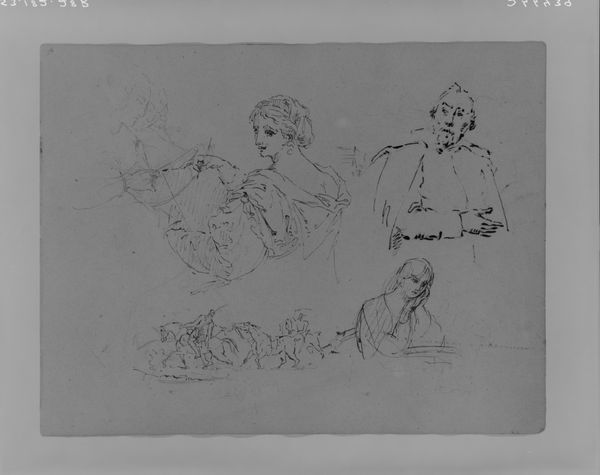

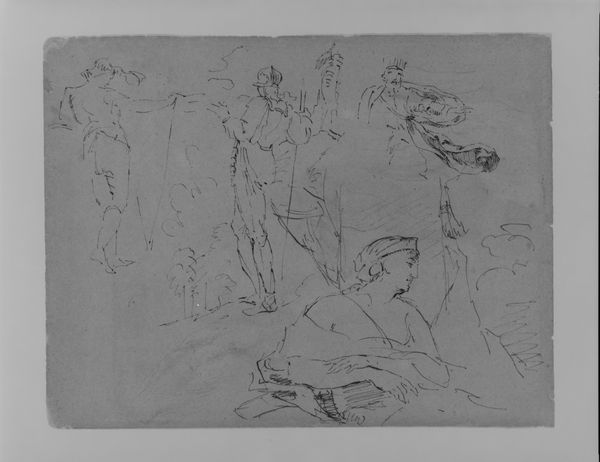

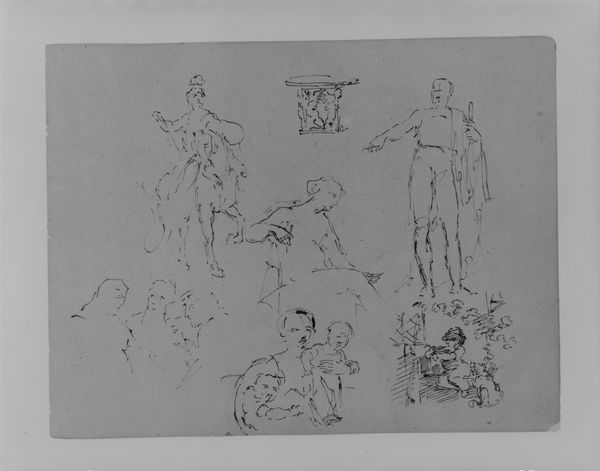

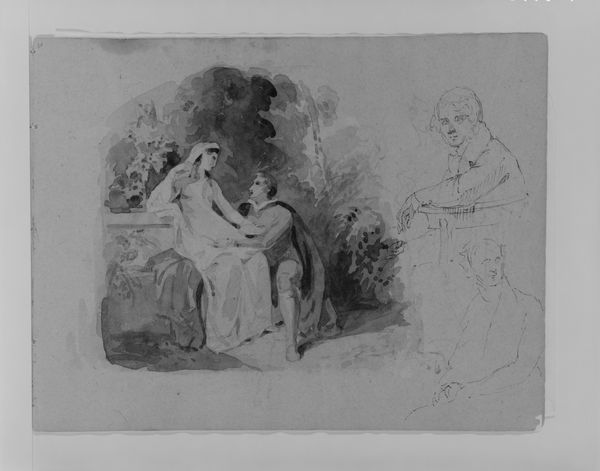

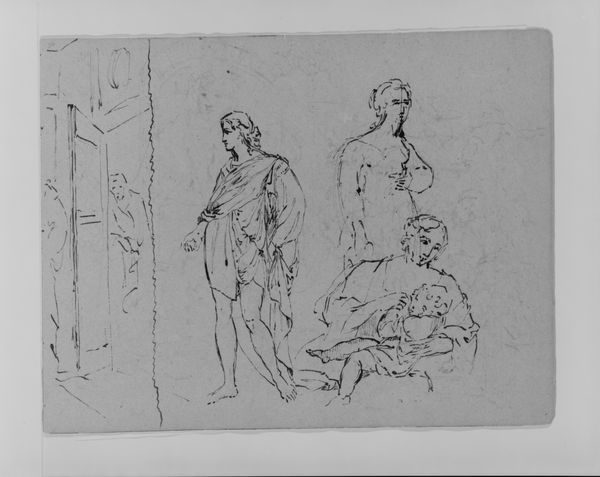

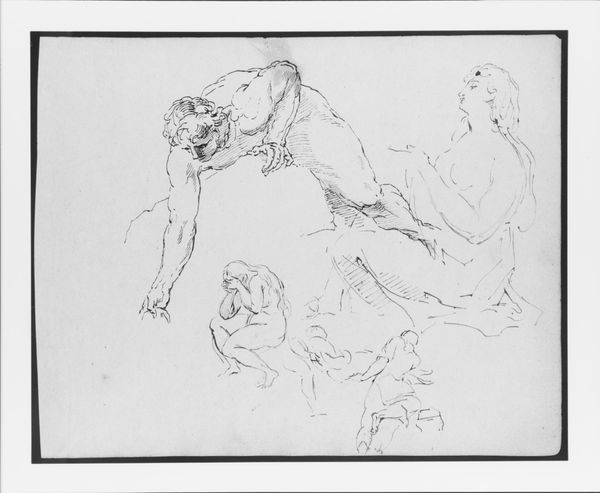

Five Figure Sketches, Including Two Half-length Steated Male Portrait Types (from Sketchbook) 1810 - 1820

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

men

#

line

#

academic-art

Dimensions: 9 x 11 1/2 in. (22.9 x 29.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Look at this intriguing sketchbook page by Thomas Sully, dating from about 1810 to 1820, currently residing here at the Met. What catches your eye first? Editor: The sheer energy of it! It feels like a quicksilver thought caught on paper. So many figures swirling around, but none fully formed. A glimpse into the artist's mind, maybe? Curator: Precisely. Sully was known for his elegant portraits, often of prominent figures. But this page shows us a more informal side. It shows process. Editor: There’s definitely a theatrical air, isn’t there? Those seated male figures… are they meant to be noble, elevated in some way? They feel posed, not quite natural, somehow. Curator: Considering Sully’s time and context, that wouldn't be surprising at all. The early 19th century portraiture was heavily reliant on ideals, societal roles, class posturing. He may well have been exploring the performance of masculinity within the context of those norms. Editor: So, almost a proto-photobooth for the aristocracy! Playful takes on identity... I like that reading. Did portraiture serve to cement those roles, make them appear unassailable, do you think? Curator: It often did reinforce them, projecting certain power structures, even perpetuating the status quo, certainly. Yet within, especially in studies like this, we catch glimpses of something beyond mere social reproduction, the beginning of an active negotiation... even a contestation. Editor: A contestation… fascinating. I hadn't thought of that! Curator: Sully seems to invite us to consider the possibilities of image, a playful invitation and negotiation. Something less expected of academic art. Editor: I came in with a vision of formality, and you've unveiled layers I wouldn’t have dreamed of. What initially looked like sketches have revealed potential. A conversation, wouldn’t you agree? Curator: That’s right. Art historical investigation at its finest; it is always conversation, with ourselves and each other.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.