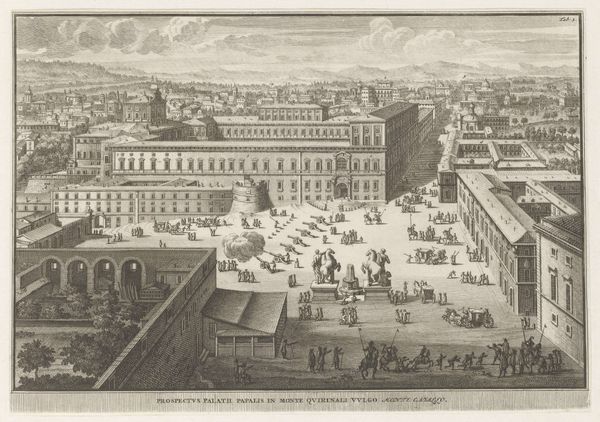

print, etching, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 325 mm, width 471 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What a beautifully rendered etching. This is "View of the Colosseum and the Arch of Constantine," created around 1666 by Lievin Cruyl. Editor: The density of line work creates a tangible texture across the scene. And yet, there’s also this profound feeling of melancholy conveyed in the state of ruin. Curator: Indeed. Cruyl, a Flemish artist working in Rome, was fascinated by the city's ancient monuments and their transformation over time. Consider how this piece offers a constructed viewpoint. He doesn't present just the grandeur of the Colosseum or Arch, but also incorporates the dilapidated, revealing Rome's layers of history. He also highlights the social reality of the place. Notice the small figures. They populate the foreground offering their wares; this serves as a juxtaposition against the timelessness of those monuments. Editor: Exactly, the framing—the architectural elements we are ostensibly looking through—serves to emphasize the Colosseum’s fragmented state. It's like a stage setting, and Cruyl invites us, the viewers, to contemplate its physical and symbolic decay. Look how the broken archway in the upper right echoes the main subject; both appear in states of gentle collapse, allowing plant life to creep up from the walls. It draws our eye toward the cityscape. Curator: It does; however, keep in mind this viewpoint may serve Cruyl's artistic purposes. Rome's elite at the time took pleasure in revisiting classical antiquity—as these antiquities are visually connected to power. Consider his patronage; did his patrons revel in such representations? This then prompts many social questions about who experiences a particular view, and why. The ability to acquire and represent that kind of vista becomes important. Editor: I concede that you’re correct that the artist and patrons must have seen the ruin in a markedly different way than perhaps the everyday Roman who existed within that cityscape. Curator: It shows the complex relationships of visual art. And the piece speaks volumes not only about 17th-century artistic tastes, but power itself. Editor: Absolutely. The interplay between ruin and composition—between decay and enduring form—that Cruyl sets out continues to generate conversation, even now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.