photography

#

portrait

#

photography

#

19th century

#

realism

Dimensions: height 83 mm, width 53 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

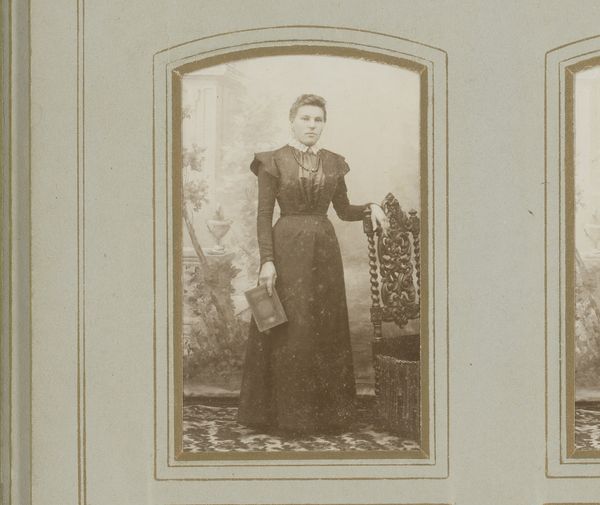

Curator: So, here we have "Portrait of a Young Woman, Standing by a Chair," a photograph dating back to between 1878 and 1886, created by Louis Robert Werner. Editor: She looks utterly composed, a little melancholic perhaps? It’s the gentle sepia tones, the stillness... Curator: Sepia does lend a certain antique dignity, doesn't it? Werner, the photographer, seems focused on capturing her essence within this structured portrait. Look at the way her dress drapes; you can almost feel the weight of the fabric. The chair beside her looks well-crafted too. Editor: That chair is integral, isn’t it? It's both prop and subtle indicator of her social standing – but even more significantly a beautifully carved object, probably created by anonymous labor! These material details bring context; we tend to gloss over how essential textiles and crafted furnishings are to such photographs. Someone wove the cloth; another meticulously shaped that chair. Curator: Indeed. It’s easy to get lost in her serene gaze, but you bring up the invisible labour! Werner likely understood this silent background—how the dress signifies more than mere fabric. Notice the delicate jewellery; hints that she may have been from the rising middle classes...a time when personal identity began to be visually solidified and commodified. Editor: It does strike me that these staged portraits, which became newly accessible to the burgeoning bourgeoisie thanks to technology, were almost like early adverts for self, but still incredibly valuable to social historians for these hints they give about consumption! And Werner, like his sitter, was implicated in the capitalist machine. What kind of photographic materials did he have at his disposal and how were they created and circulated? Curator: Yes, and his choices clearly frame both subject and her world, consciously shaping our historical gaze. Her eyes pull me in; perhaps this woman existed during such industrial change, experiencing transformations personally, caught between societal stricture and personal identity. She could've known so many feelings as the industrial revolutions spread like a forest fire. Editor: And those feelings get processed through this lens. She wasn’t photographed neutrally. Werner, consciously or not, brings to bear his era’s aesthetic ideals, mediated by the technologies of the day, to produce both art and social document, something we still examine for insights now! Curator: Quite! I'm going to be pondering the unsung textile workers tonight, thank you for giving a whole new perspective. Editor: Anytime! Thinking about it this piece reminds me to question what’s implicit in image making, how images become both art and cultural documents of production.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.