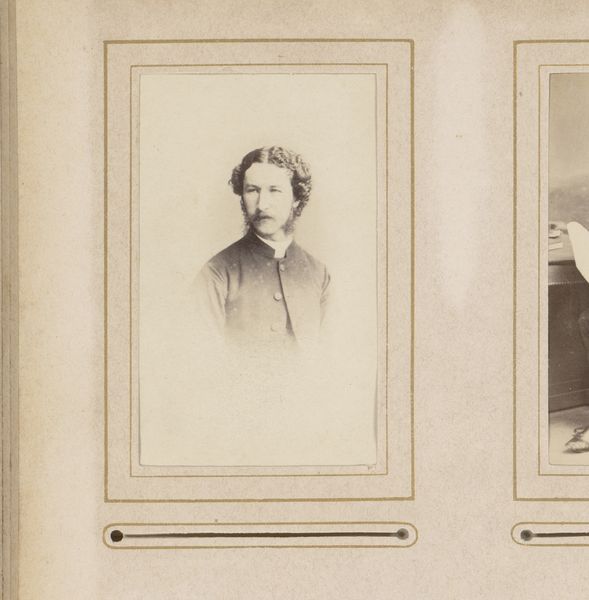

photography, gelatin-silver-print, albumen-print

#

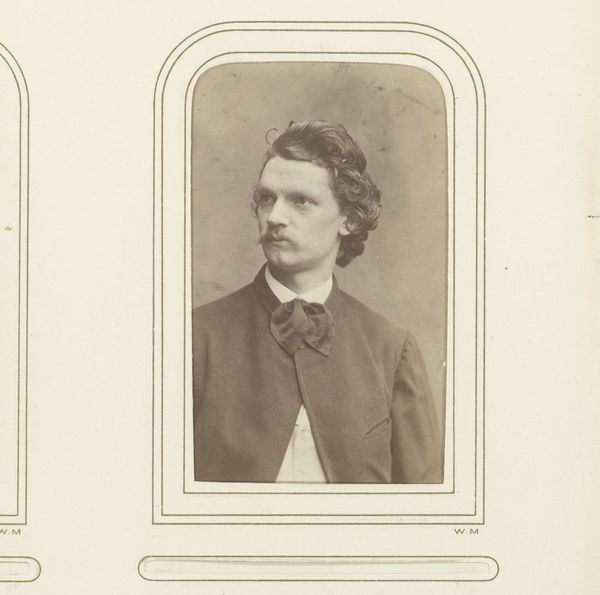

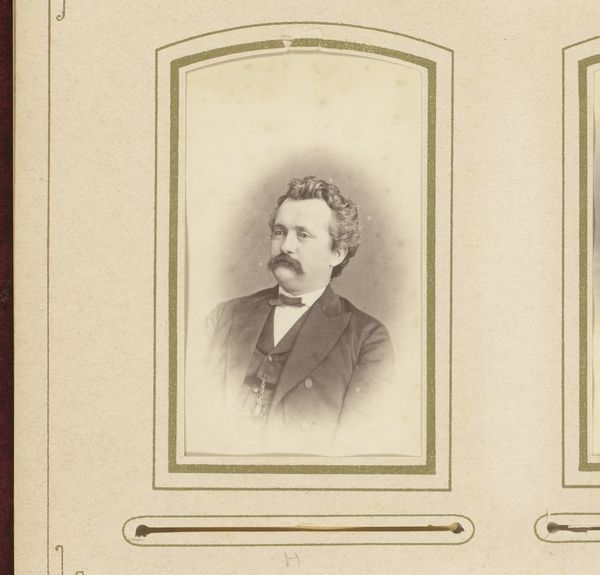

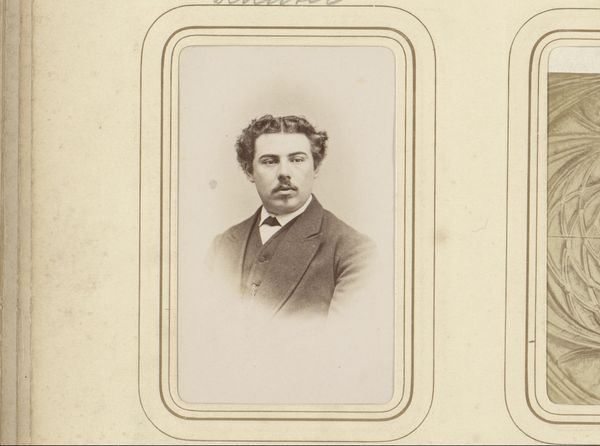

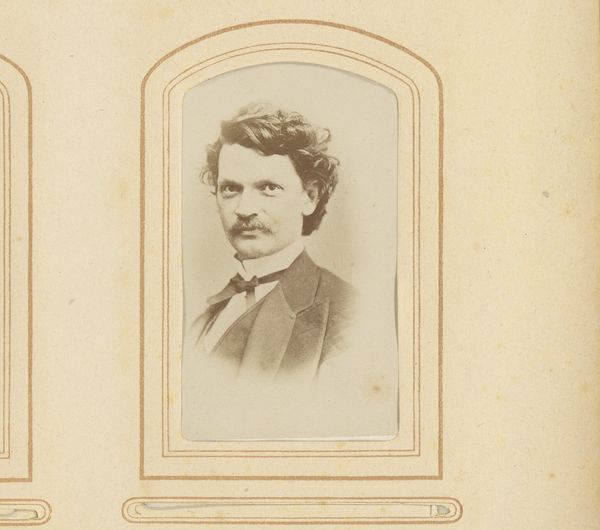

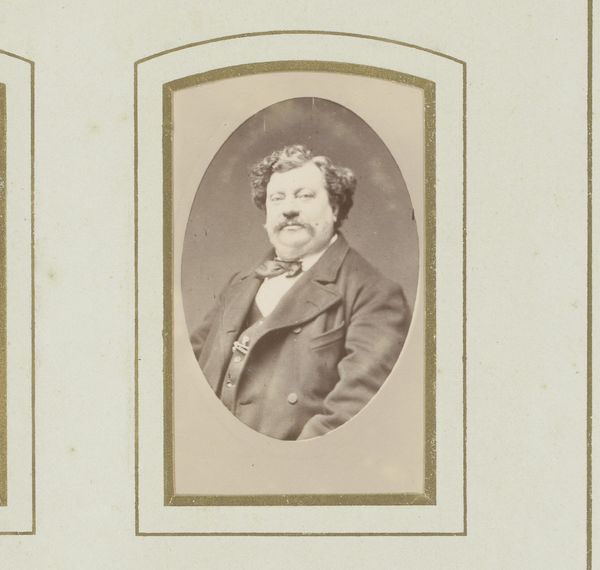

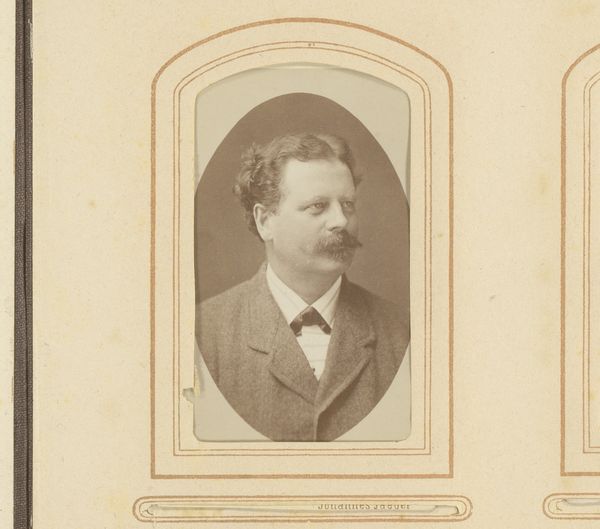

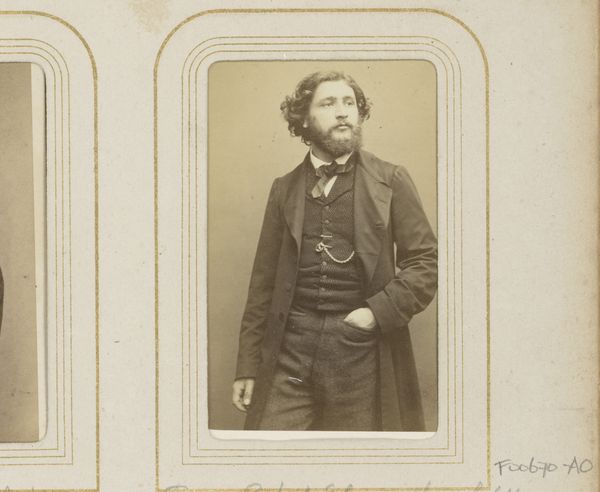

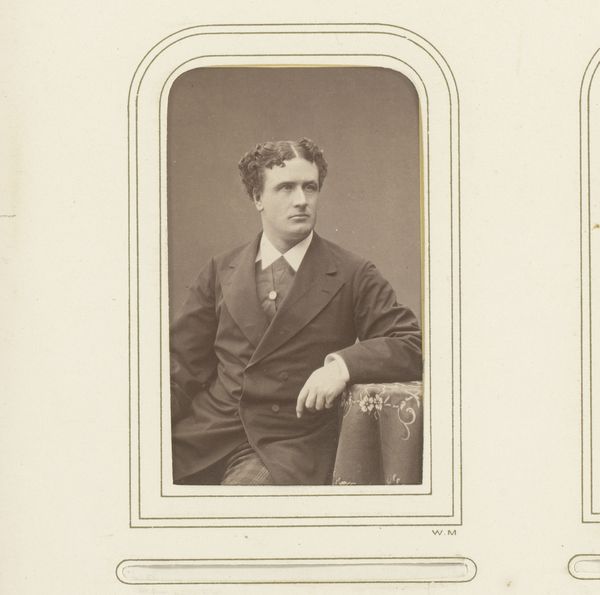

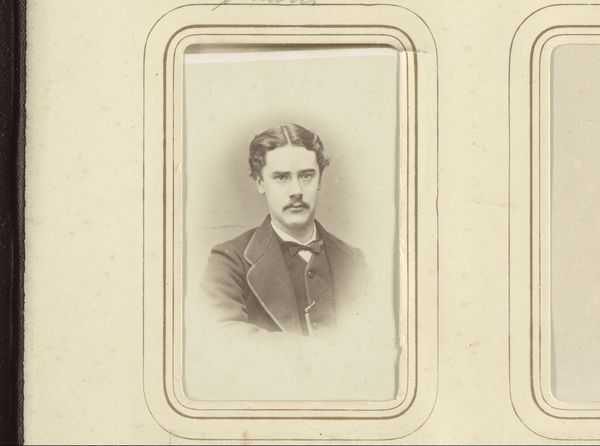

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 85 mm, width 51 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Gösta Florman’s "Portrait of Axel Elmlund," likely taken between 1865 and 1885. It’s an albumen-silver print, which gives it that wonderfully warm, sepia tone. The subject looks very dignified. What’s your take on this piece? Curator: The albumen print is central. Consider the immense labor involved in producing albumen paper, usually made with egg whites! This speaks to a societal prioritization of portraiture and image making despite its cost. Were these images considered fine art or merely documentation at the time? That's something to investigate. Editor: Documentation? But it seems so posed, so deliberate! Does the material then elevate the subject or the process? Curator: That tension is precisely where the interest lies. Look at the social context: a rising middle class desiring to emulate aristocratic portraiture, but using the comparatively novel and reproducible medium of photography. This creates a new form of visual commodity. It democratizes image production but also commodifies the sitter in a new way. Editor: So, you're saying the value isn't just in the artistic skill, but in the material itself and what it represents socially? Curator: Exactly! Think about access to photographic materials. Who owned the studios? Who could afford to sit for a portrait? Even the seemingly straightforward act of capturing a likeness becomes deeply entangled with issues of class, labor, and material availability. Editor: This gives me a lot to consider about photography. I hadn’t thought about all the labor and socioeconomic factors embedded in a single portrait. Thank you! Curator: And I am reminded how crucial it is to consider photographic history through both a lens and labor practices.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.